Spy satellites reveal Himalayan glaciers losing ground to climate change.

Keeping watch over ice on the Himalayan glaciers was certainly not the intended mission of a U.S. spy satellite program, called Hexagon, which operated from 1971 to 1986. Nevertheless, the declassified photos have revealed a rapid acceleration of Himalayan ice melt — doubling in just one generation.

A new study by Columbia University's Earth Institute finds the glaciers have been losing 20 vertical inches of ice per year since 2000, double the rate of the late 20th century. To put that into perspective, the recent amount of ice lost each year is enough to fill 3.2 million Olympic-size swimming pools and more than enough to supply drinking water to every person on Earth for longer than a lifetime.

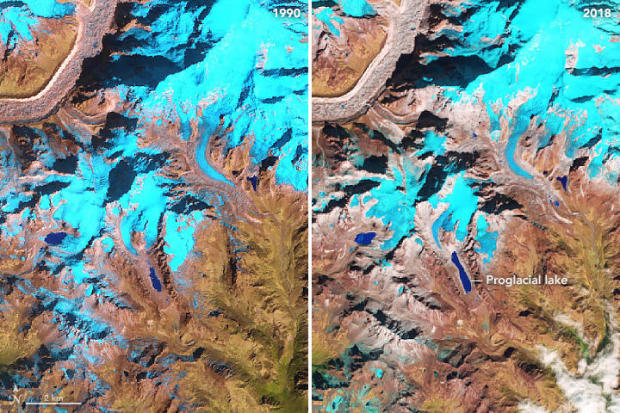

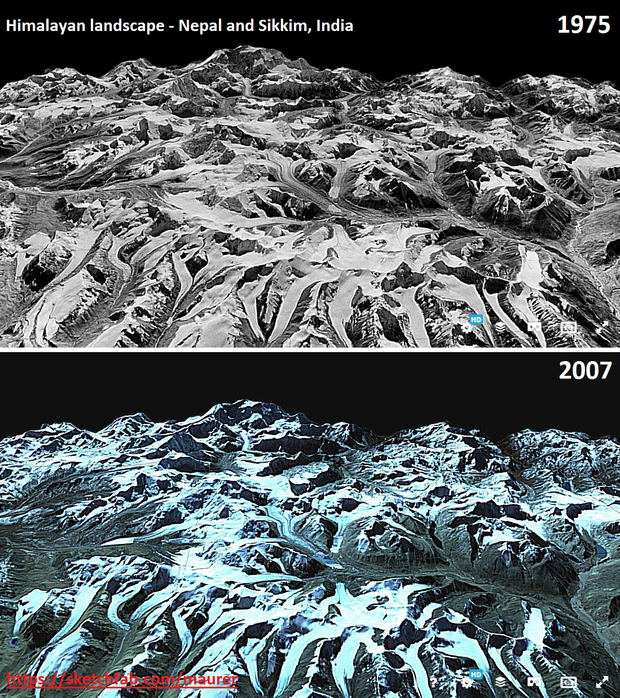

To reach these conclusions, lead author Joshua Maurer and his team took a unique approach. They analyzed 40 years of satellite images of 650 glaciers spanning 1,200 miles across India, China, Nepal and Bhutan. Much of the 20th-century data came from images taken by U.S. spy satellites. The researchers then created a system to automatically turn these images into 3D models in order to measure the changing elevations of glaciers over time. They then compared these images with more recent data from newer satellites to determine ice volume changes.

Rapid melting matters for various reasons, including the short-term potential for flooding, long-term fresh water shortages, and changes in weather patterns due to the immense size and influence of the Himalayan range.

Another recent study estimates that water flowing down the mountains each year from 2000 to 2016 was 1.6 times greater because of excess melting. As a result, meltwater lakes are swelling rapidly behind natural dams. These are threatening downstream communities with potentially destructive "glacial lake outburst floods." In Pakistan alone, the U.N. estimates 7.1 million people are at risk.

As the glaciers continue to diminish, the concern will shift away from flooding and towards water shortages. It is estimated that around 800 million people depend on seasonal runoff from Himalayan glaciers for irrigation, hydropower and drinking water.

Dr. Ben Orlove is an anthropologist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society at Columbia University and creator of GlacierHub, a comprehensive source for all things glacier related. Orlove explains that the seasonal cycle of glacial melt is vital to extend Himalayan communities' growing season and to better cope with dry years.

"Some villages have already been forced to move because glacier retreat has reduced their supply of irrigation water to levels that are unviable, and many more are threatened," Orlove said.

And while drinking water shortages are not widespread yet, they do exist.

"Drinking water is already reported as a problem in some villages in Nepal," said Orlove. "In steep mountain topography, alternate water supplies are often distant, hard to get to, and hard to haul water over." In these cases, people can be forced to migrate. Although a warming climate is not always the primary reason, Orlove says, "We are seeing cases where climate change is the key factor, and it promotes greater rates of outmigration."

Maurer agrees that human-caused climate change is the overarching reason for the fast melting. From 2000 to 2016, temperatures in the region have increased by 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit as compared to the period 1975 to 2000. Maurer says the melting,"looks just like what we would expect if warming were the dominant driver of ice loss."

Another factor for the melting is black carbon. Increasingly, Asian nations are burning record amounts of fossil fuels and biomass, launching soot into the sky. That soot eventually lands on white glacial surfaces, turning them black, which absorbs more sunlight and accelerates melting. The change between 1975 and 2007 can be seen below, with significantly less ice in 2007. The trend has accelerated in recent years.

Picture 3 million Olympic-size swimming pools full of water.

That's how much ice melts from glaciers in the Himalayas each year, a new study suggests, and climate change is the primary cause.

Even more concerning is that the ice melt has doubled in recent years: Himalayan glaciers have been losing the equivalent of more than a foot and half of ice each year since 2000 – which is double the amount of melting that took place from 1975 to 2000.

“This is the clearest picture yet of how fast Himalayan glaciers are melting over this time interval and why,” said study lead author Joshua Maurer, a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

Overall, the Asian mountain range, which includes Mount Everest, has been losing ice at a rate of about 1% a year since 2000.

The big melt: Global warming predicted to melt massive Himalayan glaciers, disrupt food production

The melting also threatens the water supplies for hundreds of millions of people downstream who rely on it for hydropower, agriculture and drinking, across a large portion of Asia, said study co-author Jorg Schaefer, a climate geochemistry professor at Columbia.

“Disaster is in the making here,” Schaefer said.

Scientists used recently declassified Cold-War-era 3D satellite images to track the glacial retreat back to the mid-1970s. By analyzing 650 Himalayan glaciers, the researchers estimate that, of the region’s total ice mass present in 1975, 87% remained in 2000, and 72% remained in 2016.

Water, water everywhere: 390 billion tons of snow and ice melts each year as globe warms

Rising temperatures are the primary cause of the melting, the study said, noting that average temperatures in the Himalayas were about 2 degrees warmer from 2000 to 2016 than they were from 1975 to 2000.

AP

The study shows that “even glaciers in the highest mountains of the world are responding to global air temperature increases driven by the combustion of fossil fuels,” said Joseph Shea, a glacial geographer at the University of Northern British Columbia who was not involved in the study.

“To stop the temperature rises, we have to cool the planet,” Schaefer told the Guardian. “We have to not only slow down greenhouse gas emissions, we have to reverse them. That is the challenge for the next 20 years.”

The study was published Wednesday in the peer-reviewed journal Science Advances, a publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

19 June 2019

CBS NEWS & USA TODAY

*Compilation