Peak oil is suddenly upon us

A year ago, if anyone in the petroleum business had suggested that the moment of Peak Oil had already passed, they would have been laughed right off the drilling rig. Then 2020 happened.

Planes stopped flying. Office workers stayed home. “Zooming with the grandkids” replaced driving to see family. A year of global hunkering yielded the sharpest drop in oil consumption since Henry Ford cobbled together the first Model T. At its worst, global demand dropped by a staggering 29 million barrels a day.

As a once-in-a-century pandemic played out, British oil giant BP Plc in September made an extraordinary call: Humanity’s thirst for oil may never again return to prior levels. That would make 2019 the high-water mark in oil history.

BP wasn’t the only one sounding an alarm. While none of the prominent forecasters were quite as bearish, predictions for peak oil started popping up everywhere. Even OPEC, the unflappably bullish cartel of major oil exporters, suddenly acknowledged an end in sight—albeit still two decades away. Taken together these forecasts mark an emerging view that this year’s drop in oil demand isn’t just another crash-and-grow event as seen throughout history. Covid-19 has accelerated long-term trends that are transforming where our energy comes from. Some of those changes will be permanent.

It’s often difficult to recognize civilization-sized shifts in behavior until after they’ve occurred. Until the pandemic none of the major oil forecasters had seen an imminent demand peak. The debate won’t end now, especially with signs that the pandemic will ease in 2021. But if we look back from here and see the oil peak clearly in the past, what follows will be the evidence of how the energy future snuck up on us.

The peak no one saw coming

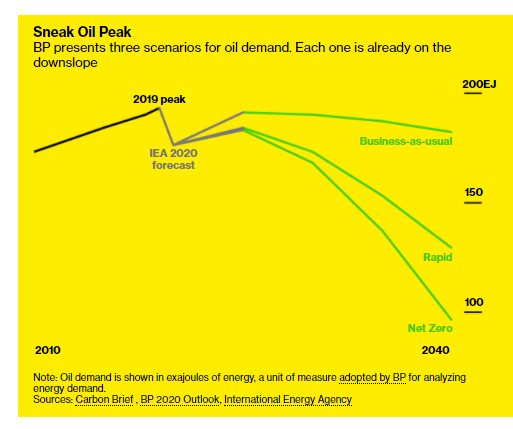

Energy analysts usually present multiple scenarios. The gap between each forecast comes down to differing assumptions about government policies, economic conditions and consumer preferences for things such as new electric cars and solar panels. A business-as-usual scenario assumes little impact from policy shifts or new technology.

Most analysts had only predicted declining demand for oil in improbably green scenarios that could only be achieved with far stronger global climate policies. What made BP’s 2020 forecast unique is that peak oil now snuck into its business-as-usual baseline. If technologies and pollution rules improve, the dropoff in demand would be even more swift.

The prospect of a 2019 peak went largely overlooked when BP released its highly regarded Energy Outlook in September. Pinpointing it was made more difficult by the fact that the company hadn’t yet included the latest real-world energy data from 2019.

The chart above updates the outlook with BP’s own oil figures for last year. It also presents estimates using BP’s calculations in exajoules—a more precise measure of energy consumption than a barrels-per-day figure. Without those changes, BP’s scenario suggested oil demand might plateau for the next decade before declining once and for all. BP didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A shakeup in oil accounting

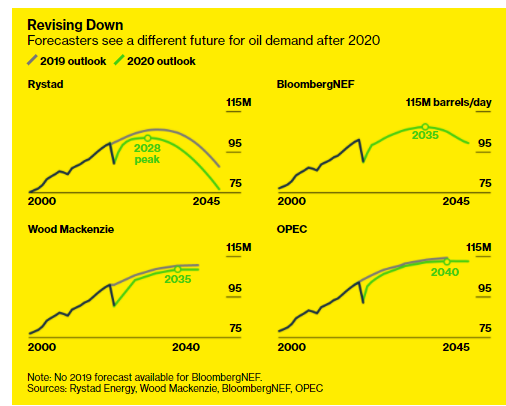

Like any forecast, only time will tell if peak oil demand happened already or won’t come until 2040. That inescapable uncertainty is less important than the newfound agreement that a turning point is here.

The list of energy analysts who now foresee a peak in oil demand keeps growing. It includes Norway’s state-owned oil company Equinor (peaking around 2027-28), Norwegian energy researcher Rystad Energy (2028), French oil major Total SA (2030), consulting firm McKinsey (2033), clean-energy research group BloombergNEF (2035), and energy-industry advisors Wood Mackenzie (2035). The exporting nations of OPEC put the peak in 2040 while acknowledging that its new forecast might still prove too optimistic for oil.

Notable exceptions include the International Energy Agency, which sees demand “plateauing” but not quite peaking, and the U.S. Energy Information Agency. Both of these agencies advise governments on policy.

Fatih Birol, who leads the IEA, said oil demand can only come down with stronger government policies promoting electric cars and regulating petrochemicals. Even though a peak isn’t guaranteed, he told Bloomberg, “the value of oil is going down” and oil-dependent economies “have to prepare themselves before it’s too late.”

The year that lasts a generation

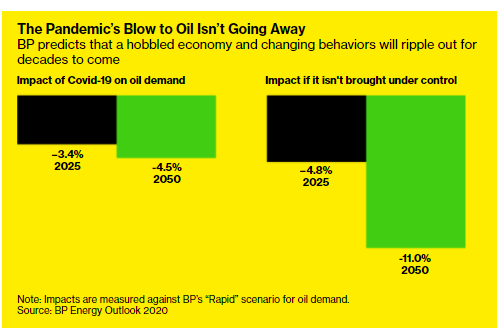

Oil prices rose this November, boosted by positive data from coronavirus vaccine trials and recovering demand in Asia. The sooner an effective vaccine can be deployed, the sooner the world can return to some picture of normalcy. But what will that look like?

“We’re not going back to the same economy,” U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell cautioned in mid-November. “We’re recovering, but to a different economy.” That new economy means people will continue working more from home, traveling less, and staying in to binge on digital programming. About two thirds of Covid’s impact on oil demand will be from setbacks to the global economy, according to BP’s estimates, and one third will be from permanent changes in behavior.

The gap between BP’s predictions for declining demand and the more bullish forecasts of OPEC and IEA can’t be explained by economic outlooks or remote work. Instead, it comes down to different readings of another shift clearly visible this year: drivers switching to battery-powered cars and trucks. Transportation slurps up more than half of the world’s crude, and three quarters of that goes specifically to wheels on the road. Forecasts for electric vehicles end up shaping the outlook for oil.

Electric cars didn’t brake for Covid

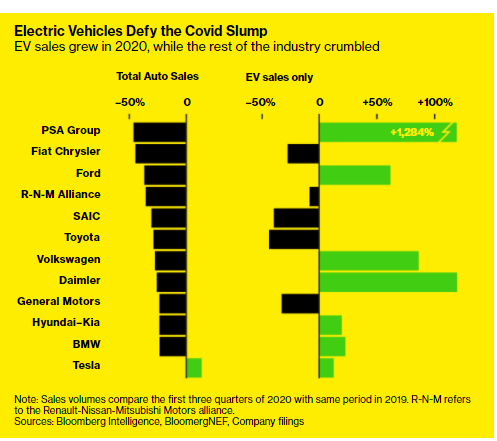

For the first nine months of 2020, car sales cratered. Every major automaker was affected—with the notable exception of Tesla. The electric automaker sold more cars than ever before. Even as the rest of the economy stood frozen, Tesla posted its longest stretch of profitable quarters and ended the year with inclusion in the S&P 500 stock index.

A closer look at the data shows it wasn’t just a Tesla story. Electric vehicles in general managed to thrive even as sales of traditional cars broke down. Both Volkswagen and Daimler saw record-setting declines in total sales, even while sales at their EV divisions doubled.

For backers of electric cars, 2020 was a gut check. It could have been disastrous. Some of the most important EV models to date were launched smack in the middle of the pandemic, including Tesla’s Model Y sport utility vehicle in February and VW’s ID.3 hatchback in September. If consumers rejected them, it could have set back EV investment by years. They did not.

At a time when the world turned upside down, sales of electric cars defied gravity.

No comeback for fossil-fuel cars

During the lockdowns of 2020, city skies cleared of pollution. Bike sales took off. Ethanol intended to be used as a gasoline additive instead made it into hand sanitizer. In many places the faltering economy wasn’t a reason to eliminate environmental regulations—it became a moment to double down.

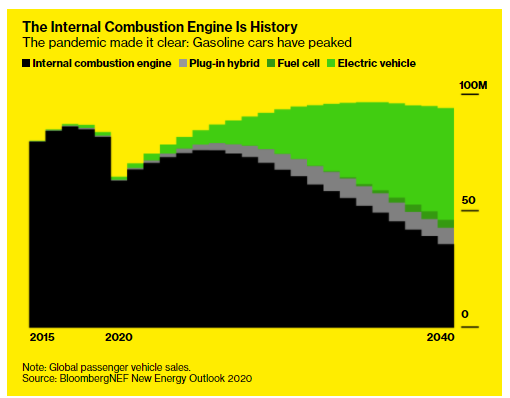

The divided fortunes of internal combustion engines (ICE) and electric drivetrains was first noticed in 2018, a year when EVs bucked the trend of slowing auto sales. Some analysts started to wonder if fossil-fuel vehicles might never return to sales levels of 2017. Back then the idea of Peak ICE was just a theory. The pandemic made it real.

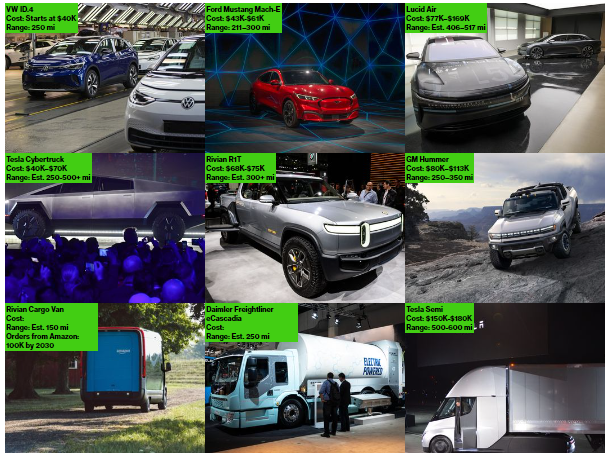

For peak oil to stick, it will require gradually supplanting more than one billion vehicles in the world. It also means batteries will have to prove themselves in challenging new markets such as freight trucks, which account for more than 15% of oil use, and gas-guzzling pickup trucks, which in 2020 surpassed car sales in the U.S. for the first time.

Batteries for everything on the road

Automakers are working on 35 new all-electric vehicles to be released next year, according to a tally by BNEF. In 2020, Tesla broke ground on a factory in Austin, Texas, to build pickup trucks and big rigs. Well-funded EV startups Rivian and Lucid Motors put the finishing touches on their make-or-break vehicles. Volkswagen sold the first cars on its new modular platform underpinning dozens of future electric models. Chinese automakers prepared for debuts in new Western markets: BYD’s Tang EV600, Geely’s Polestar 2, Xpeng’s P7.

Here are some of the most hotly anticipated models getting ready to hit the streets in 2021.

Battery cars achieved a price-parity milestone

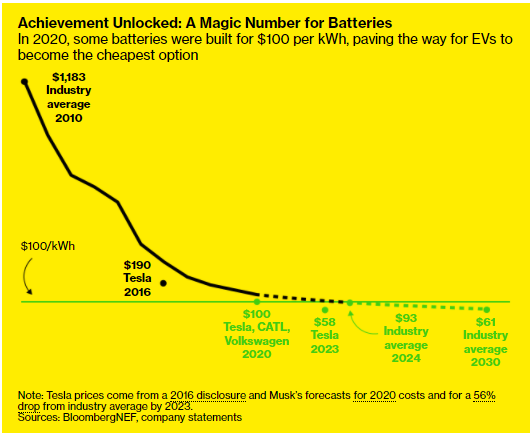

Batteries are a technology, not a fuel, which means the more that are produced, the cheaper they are to make. In fact, every time the global supply of batteries doubles, the cost drops by about 18%, according to data tracked by BNEF. Historically, EVs have been more expensive to build than gasoline cars. That’s changing.

The past year saw the first companies reaching the Holy Grail in battery packs: a cost of $100 per kilowatt hour. That’s the point that analysts have long believed will bring the cost of building electric cars in line with similar gasoline-fueled vehicles. After that, EVs will only get cheaper.

Volkswagen, the biggest automaker by cars sold, confirmed that its batteries had reached the $100 threshold for its 2020 ID.3 sedan and upcoming ID.4 compact SUV. China’s CATL, the world’s biggest battery supplier, also claimed $100 battery nirvana as it struck deals across the auto industry.

Not to be outdone, Tesla hosted an elaborate “battery day” event in September. The audience watched from a parking lot full of Teslas as CEO Elon Musk showed off plans to manufacture battery cells, a first for any automaker, and to reduce battery costs 56% by 2023. Even if Musk’s estimates are a few years too optimistic—as they sometimes are—it would still put Tesla years ahead of mainstream industry forecasts.

Mass-market EVs became possible only with the falling price of batteries. What comes next could be a virtuous cycle of cost declines. As battery prices improve, customers will snap up more electric cars, making battery prices even cheaper.

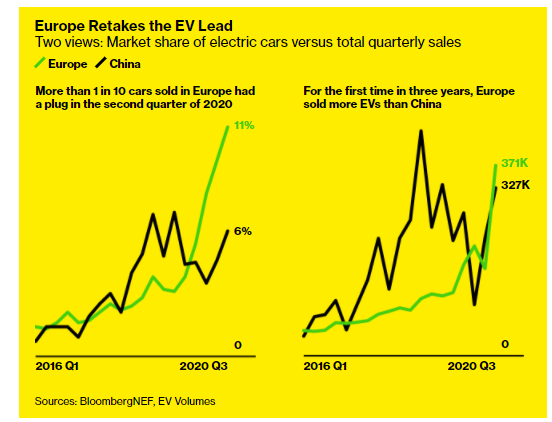

Europe’s electric push

Europe has taken back the electric-vehicle crown from China. This year, tough new EU fuel-efficiency regulations kicked in just before the virus did. Consumers responded. In oil-rich Norway, more than 70% of new cars sold in 2020 came with a plug. EV market share across Europe soared to 11% of all new cars in the third quarter, nearly doubling the adoption rate in China.

Under Europe’s new fuel-efficiency rules, companies that fail to reduce their emissions must pay steep fines or else pay a company with cleaner cars to pool emissions and avoid the fees. That option has been a boon for Tesla, creating a revenue stream big enough to pay for its first European factory. Tesla broke ground in Berlin during the pandemic and will start producing cars there next year.

In China, meanwhile, the pandemic provided an unexpected boost for EVs. As part of a pandemic stimulus, EV subsidies that were set to expire in April were extended through 2022. Then in September, the country shocked the world with a pledge to eliminate the net carbon dioxide emissions of the world’s most polluting economy by 2060. Japan and South Korea followed, vowing net-zero emissions by 2050.

The last geopolitical piece to fall into place in 2020 was the U.S., which is responsible for burning one out of every five barrels of oil in the world. President Trump had pulled the U.S. from the Paris Climate Accord, slashed vehicle efficiency standards, and allowed clean-energy subsidies to expire. Then he lost the election.

One of President-elect Joe Biden’s first moves afterwards was to name former Secretary of State John Kerry as special envoy for climate, a new cabinet-level position. Kerry, an architect of the Paris pact, vowed to rejoin it on the new administration’s first day. A push to set a 2050 end-date for U.S. emissions and a drive to clean up the U.S. electrical grid are likely to follow.

Now the three biggest global powers—the U.S., China, and Europe—are poised to push again on policies that accelerate the transition from oil. Together, the three are responsible for burning more than half of all the world’s crude.

Shifting winds of politics aren’t included in most energy forecasts, says Nat Bullard of BloombergNEF. The geopolitical backdrop gives further credence to the idea that oil demand will plateau and decline, rather than breach new highs. “This moment we’re in has accelerated a lot of change and, amazingly, kept a lot of climate-change policy on the books that could have easily been reneged on,” Bullard says.

California sets a road block for gas cars

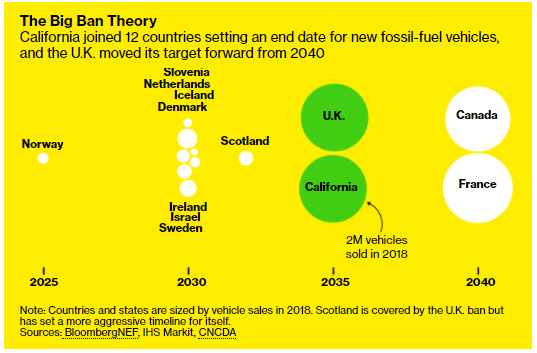

There are policy tools available for weaning the world from oil-burning vehicles. One is to simply ban them. Dozens of cities, states, countries and regions have set such targets to phase out new sales of gasoline cars. This year California joined the bunch, setting a phaseout goal of 2035. If California were a country, it would rank above Russia among the top 10 car markets in the world.

The U.K. likewise moved its goal to 2035, up from 2040 previously. Prime Minister Boris Johnson also required that any new car sold after 2030 must at least have a hybrid drivetrain capable of running on a battery.

Most of these bans aren’t codified into laws—at least not with repercussions for cheaters. Instead, policymakers use them to support ambitious policies along the way that are necessary for hitting the target. California has successfully used similar long-term targets to shape its renewable-energy policies, making it one of at least a dozen U.S. states that have policies to eventually mandate entirely green electricity grids.

21st century power transitions

At a London hotel in February, BP’s new chief executive, Bernard Looney, delivered his first speech from a podium bedazzled with a green “Reimagine BP” logo. He described one of the industry’s most far-reaching plans to cut net emissions to zero in 30 years. Two months later, Royal Dutch Shell said that it, too, would zero out emissions by 2050. In May came Total SA, France’s biggest oil producer. Spain’s Repsol and Italy’s Eni had made their own pledges back in 2019.

While key details varied—and were sometimes conspicuously lacking— “net zero emissions” became a sort of demarcation line drawn through the oil industry. Lined up against the old guard are the oil companies that no longer want to be known as oil companies.

It’s difficult to tell which came first for the transitioners. Did a changing outlook for long-term demand result in an overhaul in business strategies? Or were the forecasts for peak oil meant to justify a new business strategy born of public pressure? Perhaps a bit of both—and for the end result, it may not matter.

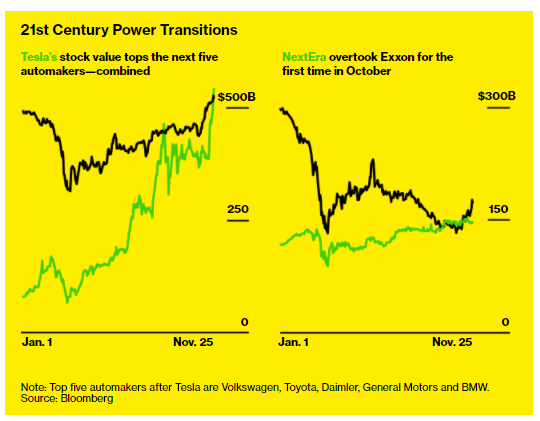

For investors, one thing is clear: the oil patch has lost its shimmer. Exxon, which was the most valuable company in the world as recently as 2013, was removed from the Dow Jones Industrial Average index this year. It’s now vying to remain above the market value of NextEra Energy Inc., a Florida-based mega-utility focused on wind and solar, which briefly overtook it in October.

Tesla’s stock this year has been on a record-breaking tear, surpassing the value of the next five automakers combined. Stock markets reward growth. Just look at Amazon’s sky-high stock price back when online retail was still a novelty or Netflix’s valuation when cable-TV still dominated. When it comes to the future of oil demand, the market is speaking very clearly.

The term “peak oil” didn’t always refer to demand. It started with the premise that the world’s supply of crude was finite. Eventually no matter how hard drillers tried, they wouldn’t be able to pull more oil out of the ground. A transportation crisis would ensue.

The peak oil hypothesis dominated economic thinking for decades. But it turned out that with fracking, deep-water drilling, and oil sands, there’s a lot more oil than we once thought. More recently, the idea of a demand-driven peak took hold. Petrostates fear it, environmentalists pray for it.

‘The writing is all over the bloody wall’

The reason so much attention is given to peak oil is that it can be a turning point from a market where oil is scarce to one where there’s more cheap crude than people know what to do with. The risk of investing in new oil supplies increases. Investors pull back. Political power wanes.

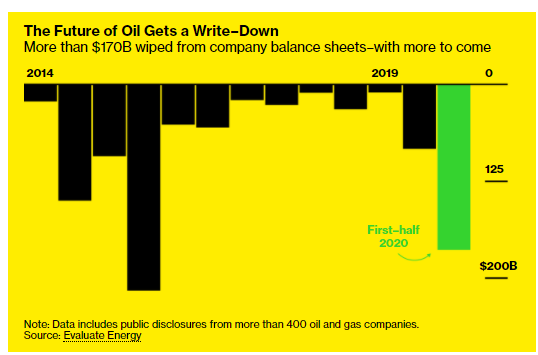

In many ways, Big Oil already began transitioning to an era of excess supply during the oil crash of 2014 to 2016. In the years preceding that crisis, oil prices averaged roughly $110 per barrel and most forecasts imagined similar prices for decades to come. Then came a glut of unexpected supply, driving prices down to less than $40. The value of oil assets was written down by more than $500 billion, according to data collected by research firm Evaluate Energy. The outlook never recovered.

In the first half of 2020, when oil demand suddenly vanished in the pandemic, oil and gas companies wrote down a fresh $170 billion. For U.S. companies, it was the equivalent of 18% of proven reserves. That’s money wiped from the books because companies no longer believed in the value of their oil deposits. And there’s more still to come. Exxon on Monday logged charges of as much as $20 billion.

The 2020 write-downs are exceeded only by the second half of 2015, the peak of the last crisis. If oil companies were only focused on the short-term pandemic crash, BNEF’s Dougherty believes the response would not have been so severe. These charges are more about faltering confidence in long-term demand—peak oil. “The writing is all over the bloody wall,” Dougherty says.

Most oil forecasts—at least the business-as-usual scenarios—estimate that even if oil demand peaks, it will continue to play a defining role in energy markets for the foreseeable future. Markets for petrochemicals will continue to grow, and both aviation and shipping will be relatively untouched.

Don’t be so sure. The same market pressures being applied to road transport and moving into other industries. Alternatives to petrochemicals are under development. Small electric planes and hybrid aircraft for longer distance are moving out of the prototype stage. It’s only a matter of time before tanker ships start running on hydrogen.

Once a technology reaches scale and price parity, conditions can change dramatically. That happened with coal, which was expected to dominate for decades—until cheaper natural gas and renewable energy came along. U.S. coal demand peaked in 2008. Nine years later Peabody Energy, the world’s largest coal producer, was bankrupt.

Sunshine is the new oil

For the last century, transport fuels and electricity generation have been almost entirely separate industries. Oil was for vehicles, coal was for power. Drillers versus miners, petrostates versus power utilities. There was very little crossover. For years, the oil industry has watched what was happening to coal and insisted it wouldn’t happen to them.

Back in 2015, ConocoPhillips CEO Ryan Lance told Bloomberg it would take another 50 years for electric cars to have a material impact on oil demand—probably not in his lifetime. That was the widely held view just five years ago. Few in the oil industry would make that case today.

With the electrification of transport, the distinction between liquid fuels and power markets is blurring. Solar power is now the cheapest form of new energy capacity in most of the world, which means that as power markets grow to meet the new demand from EVs, oil is being largely displaced by power from the sun.

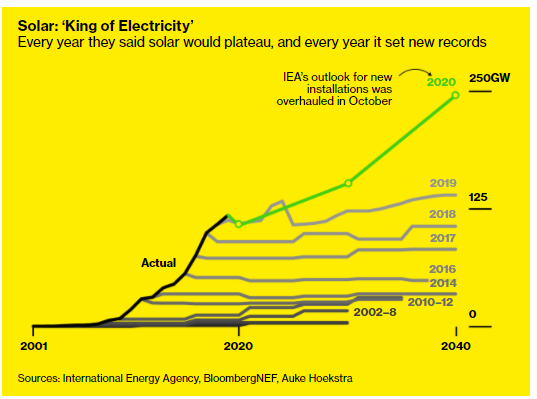

Forecasting energy transitions is painstaking work. For almost two decades, the International Energy Agency’s base scenario has consistently underestimated the rise of solar power. Every year, the models expected the rate of growth to level off, for the industry of solar installers to stop hiring. Every year it did the opposite. This record shows the hazards of basing decisions about the future on today’s policies and technologies, especially when history shows that neither stands still.

The IEA changed its view on solar this year. In the introduction to its 2020 World Energy Outlook, the IEA’s Birol dubbed solar “the new king of electricity.” He wrote that “based on today’s policy settings, it is on track to set new records for deployment every year after 2022.”

When discussing their forecasts, energy analysts take great pains to point out that they are not making predictions of what will happen but rather presenting different scenarios about what could happen. As Birol frequently points out, the timing of peak oil depends entirely on what the world does next.

1 December 2020

Bloomberg Green