The oil industry saw its opening and moved with breathtaking speed to take advantage of this moment.

Coal is now a loser around the world.

There has been no more dramatic story in the world of energy over the last 20 years than the rise and fall of coal.

In the early 2000s, coal fueled China’s rapid growth. From 2000 to 2013, coal consumption in the country grew at a ludicrous pace of 12 percent a year on average, from 1.36 billion tons annually to 4.24 billion. For a while, China was burning over half of global coal output. Coal producers across the world flourished and many believed the “economic miracle” would go on forever.

It didn’t. In the early 2010s, China’s manufacturing-driven boom began slowing, cheap fracked gas took off the in the US, the world woke up to climate change, and renewable energy began its unstoppable march down the cost curve.

The result has been an extraordinary reversal of fortunes for coal at a time when it’s clearer than ever that we must stop using fossil fuels as soon as possible.

Just how bad has it gotten? For that, we turn to the Carbon Tracker Initiative, a research nonprofit. It maintains the Global Coal Power Economics Model, or GCPEM, “a proprietary techno-economic simulation model which tracks ~95 percent of operating, under-construction, and planned coal capacity at boiler-level.” (The raw coal plant data is gathered and maintained by Global Energy Monitor.)

Basically, Carbon Tracker monitors the finances of all the world’s operating and planned coal plants. It has just released a comprehensive report on the health of the global coal power market.

The results reveal that in the US and across the world, coal power is dying. By 2030, it will be uneconomic to run existing coal plants. That means all the dozens of coal plants on the drawing board today are doomed to become stranded assets.

But while coal has lost its economic advantage, it still retains considerable social and political power. Let’s dive in.

Two key metrics to understand the results

First, two key metrics and two key thresholds to keep in mind.

The first metric is the long-run marginal cost (LRMC) of energy from a power plant, which is the value of the energy it produces minus the ongoing costs of running the plant, i.e., fuel costs, variable operating and management (O&M) costs, fixed O&M costs, and any carbon costs that might be imposed by policy.

The second metric is the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) from a power plant, which is the value of the energy it produces minus the costs of running it (LRMC) and the capital cost of building it.

If you’re thinking about whether to continue running a power plant you already own, you’re thinking about LRMC. If you’re thinking about whether to build a new power plant, you’re thinking about LCOE.

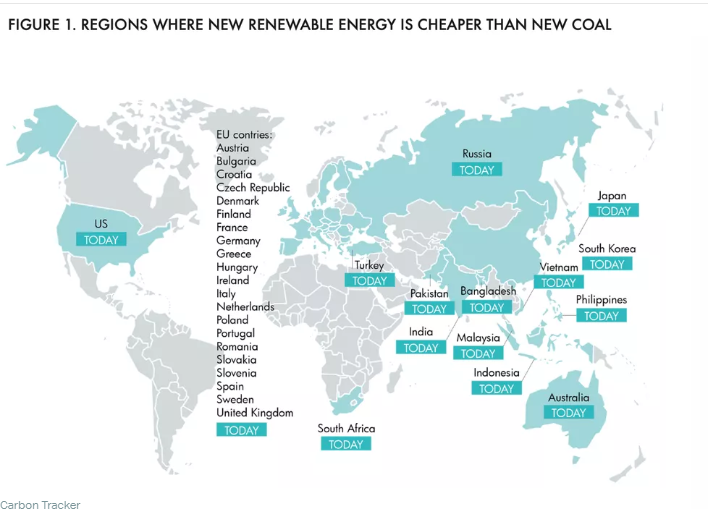

With that in mind, the first key threshold is the point at which the LCOE of a new renewable energy power plant (solar or wind) falls below the LCOE of a new coal plant — in other words, when it becomes cheaper to build new renewable energy than it is to build new coal.

The second key threshold is the point at which the LCOE of a new renewable energy power plant falls below the LRMC of a coal plant — in other words, when it becomes cheaper to build new renewable energy than to run existing coal.

These thresholds will arrive at different times for different renewable-energy technologies in different markets, of course. Carbon Tracker’s analysis charts out the numbers for each region.

4 remarkable facts about coal’s declining health

So let’s walk through the four big findings.

1. It is already cheaper to build new renewables than to build new coal plants, in all major markets.

Just two years ago, in 2018, Carbon Tracker did a similar analysis and concluded that new renewable energy would undercut new coal in all major markets by 2025. “Using updated data from publicly available sources,” it concludes in this year’s report, “we now believe these conclusions are too conservative.”

In fact, they say, new renewables are cheaper than new coal plants in all major markets ... today.

2. Over half the existing global coal fleet is more expensive to run than building new renewables.

The second threshold, Carbon Tracker finds, has been crossed by about 60 percent of the global coal fleet, which now has a higher LRMC than the LCOE of new renewable energy.

“This trend is most pronounced in the EU, which has a strong carbon price and has benefited from years of investment in renewable energy,” the report says. “The US, China, and India are not far behind the EU due to excellent renewable energy resources, low capital costs, and least-cost policymaking.”

In markets where this threshold has not been crossed, like Turkey and Japan, the blame generally falls on unsupportive policy and unreliable markets.

3. By 2030, it will be cheaper to build new renewables than to run existing coal — everywhere.

This is the real mind-blower: even in laggard markets, Carbon Tracker projects that coal power will cross the second threshold by 2030 at the latest.

In other words, within ten years, virtually every coal plant in the world will be uneconomic, producing power more expensive than what could be generated by new renewables. (And Carbon Tracker doesn’t even take into account the enormous costs of decommissioning and cleaning up after dead coal plants.)

4. Investors stand to lose over $600 billion on doomed coal plants.

Coal plants are long-term investments, built to last 40 or 50 years. There are coal plants running in the US that are over a century old. Investors’ capital recovery is typically 15 to 20 years.

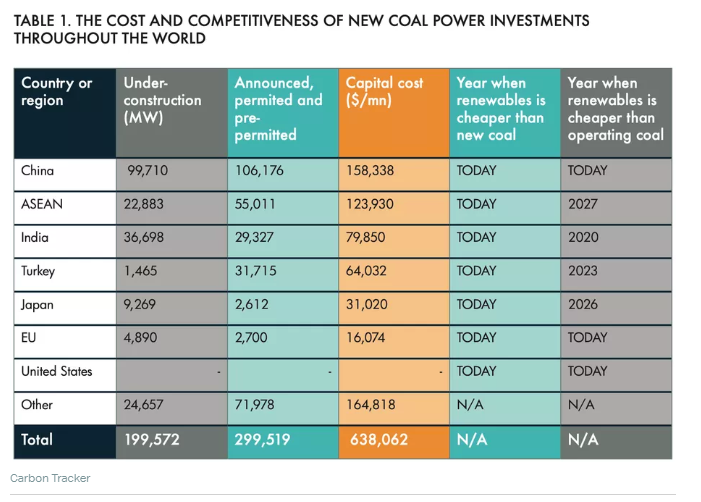

According to Carbon Tracker, 499 gigawatts worth of coal-power capacity is “announced, permitted, pre-permitted, and under-construction throughout the world.” (By way of comparison, the current global coal fleet is about 2,000 GW.) That adds up to about $638 billion worth of investment.

If Carbon Tracker’s analysis is correct, all of those plants will be uneconomic either upon being built or shortly thereafter. They will become stranded assets — and $638 billion is a lot of stranded assets.

It is not economics propping coal up

All of this raises the question: if more than half of current coal plants are uneconomic, and virtually all future coal plants will be, why are people still investing in them? How is coal defying market gravity, staying up despite the economic forces dragging it down?

Because most energy markets aren’t particularly market-like. They tend to be centrally planned and highly regulated, though they do range in the degree of regulation. The most competitive markets — “deregulated” markets where there is something akin to open competition among energy resources — are generally found in the EU. In the US, there is a mix of semi-regulated markets (with some competition) and fully regulated markets, wherein the entire electricity supply chain is controlled by monopoly utilities. The situation is similar in Asian countries, a mix with even more barriers to markets.

What’s notable is that, across the world, coal’s fortunes vary inversely with the degree of market competition. Where there is more competition, there is less coal. Where there is more corporate welfare, more monopolistic utilities, more lobbying of lawmakers and capture of regulators, more socioeconomic resistance from areas dependent on fossil fuel plants for local revenue, there is more coal.

Coal is kept alive by path dependence, political influence, and distorted markets. Killing it off for good is the capitalist thing to do.

4 ways policymakers can avoid a coal disaster

Carbon Tracker concludes with four recommendations.

The first it directs to China, though it could equally well be directed to any country. COVID-19 has dealt a serious blow to China’s economy and will deal more serious blows to other economies across the world before it is done. In doing so, it has slowed economic activity and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

Hard-hit countries are certain to turn to economic stimulus to get their economies going again. It is important for climate change that such stimulus not trigger a corresponding spike in emissions.

According to Carbon Tracker, “around 70% of China’s operating coal fleet costs more to run than building new onshore wind or utility-scale solar PV.”