UNEP chief: EU should aim for 55% CO2 reduction by 2030

The European Union needs to revise its 2030 CO2 reduction target from 40% to 55% if it wants to meet the 1.5°C global warming objective of the Paris Agreement, says Joyce Msuya.

Last year, just before COP24, the European Commission tabled a long-term climate strategy for Europe to become carbon neutral by mid-century. In doing so, the EU also became the first region in the world to debate its 2050 climate objectives. What was the reaction in the UN? Did you open a bottle of champagne?

[Laughs]. No, we did not open the champagne. But we were quite impressed by Europe’s leadership, for a number of reasons. First, because although Europe is diverse, it’s also united. So it’s positive to see all those countries coming together and discussing a long-term strategy for climate action.

And second, because it’s time-bound. You can have an infinite strategy which may not be implemented, and that brings accountability – both to citizens and policymakers.

2018 was a momentous year for climate policy in Europe. New renewables and energy efficiency targets were adopted for 2030, de facto raising the EU’s carbon reduction pledge from 40% to 45%. So did you open the champagne this time?

Yes. Because it’s ambitious, and because it shows the political will to move forward. And that’s something worth celebrating.

In my role, you don’t often see that kind of leadership very often. The new targets are in line with the sustainable development goals and for us in the UN it shows the alignment of the EU ambition with what we’re trying to achieve with the SDGs.

So, that’s worth opening a bottle of champagne, definitely.

What is your view about the state of play in Europe when it comes to meeting climate and energy objectives for 2020 and 2030? Europe may be on track overall but it’s lagging behind on energy efficiency, for example. So what’s your assessment?

Our numbers show that the EU is currently set to fall short of its 40% objective by 2030. But this goal needs to be revised to 55% if the EU wants to stay within the 1.5°C global warming objective.

So there is work to be done, there is commitment to reach that goal and we are partnering with the European Union to see how we can support it.

Getting EU countries to agree on a 45% de facto objective was already a stretch. What arguments would you put forward to encourage policymakers to go to 55%?

First, there is growing pressure from citizens. We can see very active engagement, including from the youth, who in my view are impatient optimists, putting pressure on their governments to take action. And that’s a positive thing, because politicians have to serve their people.

Second, because the EU is quite supportive of multilateralism. In September, the UN secretary general is organising a climate summit in New York, back to back with the general assembly. I was here engaging with our EU partners to see what they can contribute. I’m just coming from Singapore where the Asia-Pacific environment ministers met. And there was strong interest there to learn from Europe, which has a lot to offer to the rest of the world.

So given the demand from different parts, I have full confidence that the political will will be sustained.

Countries often take action based on self-interest. What is the EU’s self-interest in going for 55% CO2 reduction by 2030? Aren’t the costs too high? And what would be the benefits?

European policymakers can speak about it better than me. But one is the value system and the EU’s responsibility and desire to demonstrate leadership on global public goods such as climate change.

This type of leadership has emerged before in Europe. And it’s impressive to see that on a topic like climate change, they are taking leadership. I would also add: European citizens demand more action on climate change from their policymakers. And most governments will respond to citizen’s needs.

Parts of the business community in Europe have criticised the EU for “going it alone” on climate change when other countries or regions do not adopt equivalent policies. They argue this penalises businesses here. What do you respond to them?

Businesses indeed have to factor in the costs, and the jobs that may be lost. But most European governments are actually engaging with the private sector on these issues. And they often forge public-private dialogues. On issues like plastics for example, they support factories to produce less or even eliminate single-use plastics. That is just one example.

Let’s imagine the EU opts for climate neutrality by 2050. What difference would it make on a global level? Would it make a big difference between 1.5°C and 2°C of warming?

I would quote Federica Mogherini, the EU high representative for foreign affairs and security policy. She said: “When we invest in the fight against climate change, we invest in our own security”. So whether it’s migration or global public goods, it’s a matter of self-interest for Europe.

Europe can lead on the global stage to drive this agenda. But in order to lead, you have to demonstrate results, starting from home. So this ambition actually reflects that.

Number three is what I’ve said before: it’s the value system of most Europeans. And you can see this with the climate marches that are ongoing across Europe.

How fast is the window closing for keeping global warming within 1.5°C?

Time is running out. We have to act now, there is an urgency of making choices and we just don’t have time to wait. We see the impact of climate change across the globe, including in Europe. So it’s up to us collectively to come together and act as soon as possible.

Is there a date that UNEP has identified beyond which there is no more hope of meeting the 1.5°C objective?

At UNEP, we are very optimistic, on anything to do with the environment across the globe. We are now focusing on the UN’s vision 2030 as part of the sustainable development goals. And in 2030, we’ll take stock of where we are.

This is why the UN secretary general is having the New York climate summit in September – to raise the political engagement but also to take stock on where we are on climate change.

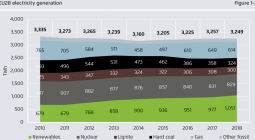

What kinds of transformations are needed in your view to achieve carbon neutrality? There are calls for example for countries to phase out coal entirely by 2030 at the latest. But Germany said it will only achieve this by 2038. And other countries like Poland have no coal phase-out plan at all. So what’s your view on this, should a firm date be set to phase-out coal?

Ambitious targets should be set for stopping unsustainable sources of energy. The EU, as you know, has led in terms of strategies and targets that are time-bound.

Industrialised nations in Europe need to think about how to green the energy sector – in manufacturing, in industries or transport in cities. There are some good examples, for example in the Netherlands. There are also some developments on green buildings in Europe that have to be commended.

So looking at each country separately, and seeing where the gaps are, will lead to a transformation.

Water re-use is another example, where Belgium and the Netherlands are leading. And we are getting requests from countries in Asia who are interested to learn how they were able to transform their water sector.

Europe can look at what it’s done thus far, and where it can lead. And we as an international organisation can help share those achievements this with other countries around the globe.

In terms of renewables, there is a lot of talk about wind and solar, which are growing fast. However, biomass today makes up 50% of the total renewable energy consumption. And plant growth also absorbs CO2, which is a way of storing carbon dioxide. So do you believe biomass should be further encouraged?

There is a big potential for biomass but a lot of research and development needs to be done. This is where Europe can lead – by doing more research, including on the cost efficiency aspects as well as the costs of transitioning into biomass. Europe can also help identify what works well vis-à-vis biomass, in what industries it brings the most benefits.

So we’re looking at studying it more – it’s a relatively new area – and see where we can support pilots for biomass usage.

You say biomass is relatively new but it’s also the most ancient source of energy. So what areas have you identified?

For now, we’re testing the appetite for biomass. Advocacy is one because although biomass is ancient, it has also been forgotten in some parts of the industrialised world. We don’t have the capacity of doing research so it’s mostly advocating governments and EU member states to look more into biomass as one of the options.

In other parts of the world, where it’s still very ancient, we’re looking at technical assistance to see how biomass can be harvested as a source of energy.

Are you talking about biomass for electricity or for the production or transport fuels?

We’re mostly talking about electricity for now. But our thinking is still evolving.

Turning to a different subject, which is an emerging topic in the climate change debate: What do we know about methane emissions? Is the UN doing anything to better understand methane emissions and start tackling it?

We’re currently not heavily involved in methane research. We may go into that route in the next few months, but given our limited resources, we haven’t really focused on it. That said, we are keeping a close eye on it.

You mentioned the climate demonstrations taking place across Europe, with children sometimes even skipping school in protests against government inaction on global warming. Do you expect this mobilisation to be reflected as well in the ballot box at the European elections in May this year?

These types of marches are catalysing action in Europe. Here in Belgium, the Prime Minister met with the students. And the marches are also raising awareness about climate issues across the globe. People are calling us from the US and Canada saying, “Wow, how did they get this organised?”.

There is also an underlying interest in how those marches came about, including youth education in the classroom around climate issues. You don’t see that globally and this is raising a lot of interest – how do you incorporate climate education into school curricula in order to catalyse action.

So I would expect most policymakers in Europe would listen. After all, this is the future generation and they were more than 70,000 in the streets last Sunday (27 January). And the cost of inaction on climate change will impact this youth.

So at the UN, we’re looking at how we can engage with the youth and how we can learn from this experience to catalyse our own actions.

Joyce Msuya is a Tanzanian microbiologist and environmental scientist currently serving as Acting Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

She was named Deputy Executive Director of UNEP in May 2018, succeeding Ibrahim Thiaw of Mauritania. Before that, Msuya served as an adviser to the World Bank in Washington, DC.

4 February 2019

Frédéric Simon

![]()