Africa is Planting Tens of Millions of Trees in the Desert. Here’s Why.

In the dusty, windswept lands of Niger, there once stood a lonely acacia tree. Caravans passed beneath its spiky branches — the last stop before the endless sea of sand. Known as the Tree of Ténéré it was the only one for hundreds of miles — the loneliest tree on Earth.

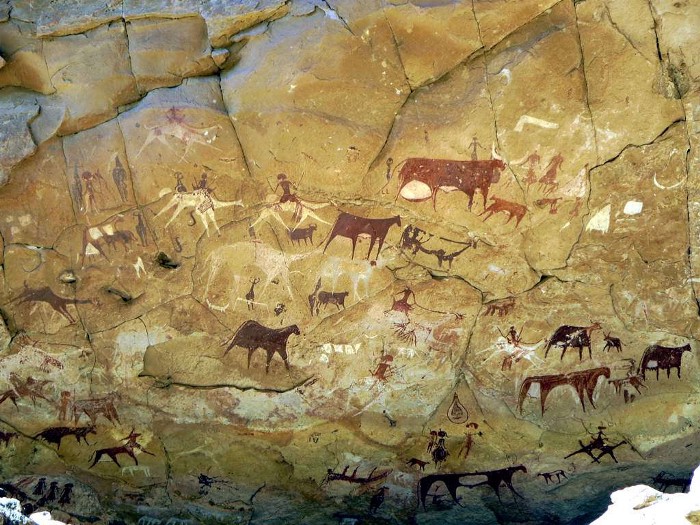

But it was also a reminder of a long-forgotten time when the Sahara teemed with life. Beautifully painted prehistoric rock art tells of a panoply of hippos, rhinos, elephants, giraffes and antelopes. For millennia they thrived in a land of oceanic lakes and thundering rivers.

That was 6,000 years ago.

Today, the Sahara is the largest warm desert on Earth, spreading from the Atlantic to the Red Sea — an area bigger than the continental US. And it’s advancing. For the communities that live in the Sahel — a thin strip of hope bordering the desert’s southern edge — livelihoods and futures are under an all-out assault.

For centuries, the Sahel — meaning coast in Arabic — was the breadbasket of the African civilisations that thrived on the desert caravans, which sailed across the sands like ships on the ocean. From Wagadu, the Mali and Songhai Empires, and the Horse-lords of the Mossi Kingdoms in the west, through to the ancient Aksumite Dynasties in the east. But their success was reliant on the fragile grasslands and scattered trees.

Now the futures of their inheritor nations are at stake.

Climate change and centuries of overgrazing are decimating the Sahel. Bordering the desert, an estimated 500 million people live on land undergoing desertification. If we do nothing, people will move. The ensuing refugee crisis will be biblical, making the mass migrations of the past decades seem quaint by comparison. Already farmers and pastoralists abandon their ancestral lands, as millions of Ethiopians are pushed into food insecurity by drought.

Across the Sahel, desperation is breeding extremism: political and religious. Boko Haram in Nigeria is only the beginning of ethnic and religious tensions in the ‘extremely volatile’ region. Considering the Syrian Civil War was exacerbated by water shortages, the Sahel looks like a tinderbox in search of a spark.

But there is an alternate vision: the boldest ecological plan ever put into action.

It’s called the Great Green Wall.

Elevens nations squeezed by the desert — Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, Chad, Niger, Nigeria, Mali, Burkina Faso, Mauritania, and Senegal — are linking arms to protect their lands against the advances of the hungry Sahara. The plan is simple: plant trees. Lots of trees.

First put forward by Burkina Faso’s legendary Captain Thomas Sankara, who proclaimed ‘the desert is at our gates. It’s already upon us.’ Ever a man of action, Sankara proposed the creation of a park of 10 million trees. Later killed by a military coup, he never saw his vision fulfilled. But he had planted the seed.

In 2007, the African Union put forward a proposal for a 4,350-mile cross-continental barrier. The project would create more than 350,000 jobs and salvage 18m hectares of land.

Progress has been slow. By 2020, the Sahelian nations had only completed 4% of the project. Ethiopia had done the bulk of the work — planting 5.5bn seedlings and creating 792,000 new terraces. In contrast, Burkina Faso had only planted 16.6m plants and seedlings, and Chad a mere 1.1m.

Even worse as many as 80 per cent of the planted trees had likely died. “If all the trees that had been planted in the Sahara since the early 1980s had survived, it would look like Amazonia,” remarked Chris Reij, a senior fellow at the World Resources Institute and sustainable land management specialist.

Is the Great Green Wall another bureaucratic sinkhole, swallowing money and delivering little?

Not exactly.

The tree planting plan was doomed from the start. It was always more a political stunt thought up in a boardroom in Addis Ababa than an ecologically sound defence against desertification. Dennis Garrity, a senior fellow at the World Agroforestry Centre, put it bluntly, ‘This was a stupid way of restoring land in the Sahel.’

But it did serve a useful purpose: galvanising the Sahelian peoples to devise cheap and practical solutions. With help from planners and environmental specialists, a mosaic landscape was created, carefully controlling water use and plant life to improve crop yields and mitigate climate change. Deep pits were dug to improve water filtration. Stone barriers erected to prevent run-off. If trees grew naturally, they were protected, with farms functioning around them.

Reij, who had first begun working in Africa in 1978, was astounded upon his return to Burkina Faso and Niger. Gone were the dust storms and baked earth; what he saw was a sea of green. Hundreds of thousands of farmers used the modifications to restore land upon which around 3 million people were reliant. By 2004, Niger’s Zinger Valley showed 50 times more trees than in 1975. Audiences were astonished when shown the pictures.

‘This can’t be Niger. It looks like Ireland’, went the response.

Sankara had prophesied that only by empowering local communities would the fight against the desert be won. His words now bear fruit. With techniques spearheaded by the locals, the desert is retreating for the first time in 6,000 years.

7 February 2021

Medium