Rebound in carbon emissions expected in 2021 after fall caused by Covid

Scientists brand 7% decline a ‘drop in the ocean’ and call on governments to push ahead with structural changes.

Greenhouse gas emissions, which plunged by a record amount this year because of the coronavirus pandemic, are set to rebound next year as restrictions are lifted further and governments strive to return their economies to growth, according to a global study.

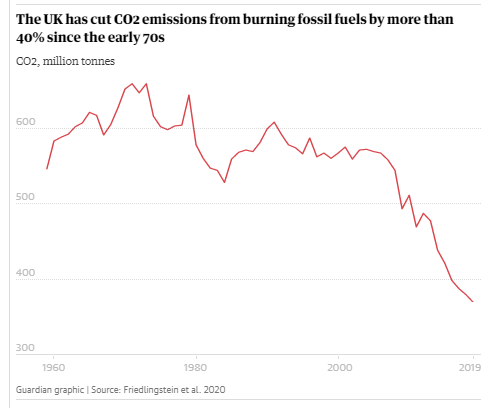

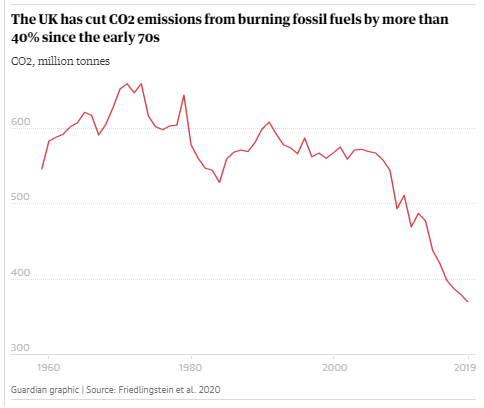

The UK showed the second biggest fall in emissions globally, down 13% for the year compared with 2019, with only France showing a larger drop, of 15%. The plunge reflects the prolonged and severe lockdowns in both countries, with surface transport particularly affected.

The record 7% global fall in carbon of 2.4bn tonnes reduced emissions from fossil fuels to about 34bn tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2020, according to the Global Carbon Budget report, the most comprehensive analysis of the world’s carbon output, published on Friday.

But a rebound next year is almost certain, according to the scientists behind the study, because the drop was the result of temporary behavioural changes rather than structural reforms. China’s emissions may even be level for this year or have increased slightly since 2019, as the country entered and left lockdown sooner than other countries, according to some of the data that fed into the final assessment.

Corinne Le Quéré, professor of climate change science at the University of East Anglia, who contributed to the analysis, said: “It is clear that emissions are edging back to 2019 levels already, but it is too early to say what the rebound will be in 2021. Whether they come back to 2019 levels or peak even higher – the economic stimulus packages will make a difference.”

She pointed to the global financial crisis of 2008-09, when emissions last fell. “There was a really big rebound in 2020, from the economic stimulus packages by governments,” she warned.

Governments still have the opportunity to make some of the changes forced by the pandemic and lockdown permanent. For instance, if more people continue to work from home, and if cities are made more friendly to cyclists and pedestrians, that could make for a long-term reduction in carbon.

Other structural changes, such as constructing more renewable energy generation and switching to electric vehicles, would take longer than the next year to have an impact but should be pursued urgently to bring down future emissions, the study’s authors said.

Analysis by the Guardian and Vivid Economics has shown that the “green recovery” around the world has stalled, with governments continuing to pour money into high-carbon activities.

More than 70 world leaders are expected to confirm pledges on reducing emissions this weekend, at a virtual Climate Ambition Summit to be hosted jointly by the UK prime minister, Boris Johnson, the French president, Emmanuel Macron, and the UN secretary-general, António Guterres. The summit marks the fifth anniversary of the landmark Paris agreement on climate change, and is intended as a staging post to vital UN talks to be held next November in Glasgow, called Cop26, where nations must set out plans for drastic carbon cuts in the next 10 years to fulfil the Paris goals.

“Pledges [to reach net-zero emissions] are not enough,” said Le Quéré. “Action is extremely lagging and most countries do not have a plan for net zero.”

Dave Reay, professor of carbon management at Edinburgh University, who was not involved with the study, said the record drop was still only a “drop in the ocean” when it came to the stock of carbon dioxide humanity has already pumped into the atmosphere, which is expected to reach 412 parts per million (ppm) next year. It is the stock of atmospheric carbon that determines the impact on the climate, and stabilising the level of carbon in the atmosphere will require the whole world to meet net-zero emissions.

Cameron Hepburn, director of the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment at Oxford University, also not involved in the study, said the scale of the problem required much stronger action from governments. “The record 2.4bn tonne decline in emissions in 2020 is small beer compared to our annual 40bn tonnes that needs to go to net zero every year. The pandemic shows that radical personal behaviour changes are one part of the story – systems change including a rewiring of the economy to clean technologies is necessary to get to net zero.”

Johnson has pledged to cut the UK’s emissions by 68% by 2030, compared with 1990 levels, to encourage other countries to come forward with similar plans at Saturday’s summit. The first slice of funding intended to help reach that goal was announced on Thursday.

The 68 grants, totalling nearly £40m, which have been announced under the green recovery challenge fund include projects to restore rivers, protect chalk streams, plant wildflower meadows and research grey seals. Taken together the 68 projects will result in the planting of 800,000 trees.

The Youth Hostel Association has been awarded £2.5m to help young people from deprived areas gain access to nature, while the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare will receive £580,400 for improving access to green spaces at hospitals and NHS sites across England, including outdoor ecotherapy sessions and a project that will enable chemotherapy treatment to take place in a garden.

Rebecca Pow, environment minister, said: “These projects will drive forward work across England to restore and transform our landscapes, boost nature and create green jobs, and will be a vital part of helping us to build back greener from coronavirus.”

11 December 2020

The Guardian