Guest post: Coronavirus food waste comes with huge carbon footprint.

As the coronavirus pandemic disrupts supply chains around the world, it is likely that more food is being wasted than ever before at a time when more people are also going hungry.

With such waste already accounting for around 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions, this could also have serious implications for the food system’s climate impact.

Based on reports as the pandemic began to take hold, I estimate that early food losses from the US meat sector alone have resulted in a carbon footprint roughly equivalent to a small country.

The World Bank reported in August that the overall food system has actually held up relatively well in response to the global pandemic. Prices have not increased significantly and trade has been flowing as usual.

However, the UN has warned that lost incomes and livelihoods could double the number of people facing acute hunger – and, when we look closely at food supply chains, cracks are starting to show.

Specifically, disruptions in food markets and workforces are causing large increases in wasted food.

As well as less food getting to those who need it, this also means huge amounts of land have been used and fertiliser, energy and water have been wasted, creating emissions for nothing.

Cancellations and bottlenecks

The first supply-chain shocks leading to food waste were order cancellations by the hospitality sector.

The western food system is fine-tuned to market sectors, so this proved problematic. Very little produce aimed at the hospitality sector can be redirected to shops, for example, because of packaging, contracts and even types of food.

Even though we – presumably – eat the same amount of food when at home as when we eat out of home, we do not tend to eat exactly the same things.

Milk consumption is one example. As a result of such supply chain disruption, during early lockdown 14m litres of milk per day were going to waste in the US, resulting in a carbon footprint of about 1.6m tonnes of CO2e (MtCO2e) in two months.

Products are also processed and packaged differently for restaurants compared to supermarkets. The difficulty of adapting to this has resulted in enormous volumes of waste.

The second type of supply-chain shock leading to waste are labour shortages. In the UK and the US, there have been shortfalls in seasonal workers from Eastern Europe and Mexico. In India, migrant workers are confined to their home villages, leaving fresh fruit unpicked and rotting in the fields.

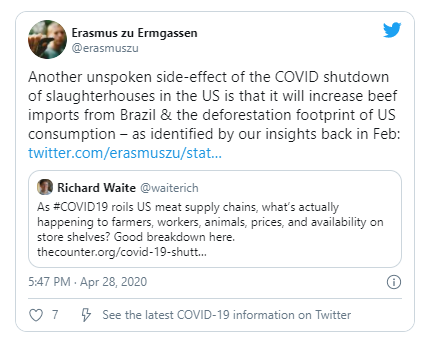

These issues are causing bottlenecks further down supply chains. In the US, about 40% of slaughterhouses closed in April because they emerged as epidemic hotbeds due to working conditions. This, in turn, led to huge numbers of livestock being culled without being used for food.

The UK has also seen coronavirus outbreaks in meat slaughterhouses and processing factories, leading to frequent closures.

According to early reports, at least 10m chickens have already been culled in the US and the same is expected for 10m pigs. The beef sector is less affected as animals can be kept for longer, but not completely spared.

Animal welfare aside, this has a tremendous carbon footprint, as meat production is far more greenhouse gas-intensive than the production of plant-based foods.

Based on these reports and available data from the sector, I have estimated the embodied carbon footprint of US livestock and dairy losses alone to be at least 7.1MtCO2e.

This is comparable to the total annual emissions of a small country, such as Cyprus, or the yearly territorial emissions associated with 860,000 UK citizens.

Meanwhile, in the EU, the carbon footprint of wasted potatoes alone – a food with one of the lowest carbon footprints – would still come to 0.5MtCO2e.

Building better systems

The food resilience research community has previously focused mostly on risks associated with changing climate and extreme weather.

We, perhaps, took for granted that skilled people in the right place at the right time are as essential as the right weather when it comes to keeping the food production wheels turning.

Agriculture is one of a few large industries that is not located where its workers are – it is located where suitable land is. It is assumed that when needed, workers will come. This has been a blind spot when it comes to food system resilience.

As food is perishable, farmers and other actors in the food supply chains only have very narrow time windows in which to harvest, prepare, sell and move food. Even in normal circumstances, this leads to waste as this window is often too narrow to make adjustments when circumstances change.

Food waste researchers and activists have long championed interventions improving access to processing equipment that increases shelf life, such as coolers and drying units, and better storage facilities.

Such interventions, which could reduce waste and, at the same time, improve rather than hamper food system resilience, have recently been reviewed in a journal paper.

The storage capacities that we do have reportedly filled up quickly in the first few weeks of the lockdowns food that had already been produced had nowhere to go.

In the name of food waste reduction, there have also been calls for improved flexibility for farmers in terms of contract obligations, freer access to markets and product diversification.

Had these solutions already been widely in place, a significant part of the crisis-induced food waste could have been prevented, saving greenhouse gas emissions.

Cutting household waste

One silver lining is there are good indications that food waste in households – the largest contributor to food waste in high income countries – has reduced during lockdowns.

People initially panic-bought more food than they needed, resulting in reports of an increase in food waste, but there are also signs the pandemic has instilled a newfound appreciation of food supply chains.

A biannual survey run by the UK’s Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP) supports this.

As the UK’s lockdown got underway in April, it showed people adopted, on average, six new behaviours to manage their food better and self reported a 34% drop in how much they were wasting.

With whole households confined indoors it should be easier to estimate how much food will be eaten at home and, perhaps, people also have more time to manage their food and use leftovers.

The other epidemic

There is another epidemic hiding in the shadow of coronavirus that is also causing large amounts of waste. African swine fever caused China to lose up to 40% of its 360m pigs last year.

How such losses will affect climate mitigation in the long term is uncertain. The US and China are both already looking to Brazil to fulfill their meat demand, signing long-term contracts that will dramatically increase the nation’s meat production.

This cannot be good for deforestation in the Amazon, but maybe high meat prices will also translate into long-term reduction in meat consumption habits.

All of this demonstrates that when it comes to food, health and the climate, everything is connected. It is difficult to predict how changes in one will impact on all of the others.

But one thing is certain: wasted food is bad for the climate, as it means that we do not make the best use of the food produced and we keep producing more than is needed.

We are at a fork in the road where we can either harvest or waste the lessons learned from the epidemic.

17 September 2020

Carbon Brief