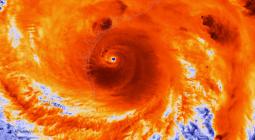

A More Active Hurricane Season Could Lie Ahead, Scientists Warn.

Federal weather researchers expect hurricane activity to be greater than normal for the rest of this year’s season, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said Thursday.

The new analysis suggests that an above-average season is substantially more likely than the agency first predicted in May. NOAA now expects up to 17 named storms before the season ends on Nov. 30, with as many as four of those becoming major storms with winds of 111 miles per hour or more.

The forecasters initially suggested a season with a normal level of hurricane activity, with 12 named storms and three major hurricanes. They based that forecast on the continued presence of an El Niño, the Pacific Ocean heating pattern that tends to suppress hurricane activity, and the likelihood that it might persist into October.

But NOAA issued an updated El Niño report on Thursday stating that conditions had returned to a neutral status, which will eventually allow hurricane formation to ramp up. The forecasters at NOAA’s climate prediction center thus raised the likelihood of an above-normal season in the Atlantic to 45 percent, up from 30 percent in the May forecast. The chances of a below-normal season have dropped to just 20 percent.

The peak of hurricane season is beginning now, and two named storms have already formed this year, including Barry, which made landfall last month on the Gulf Coast.

The impact of climate change on hurricanes is becoming more clear over time. Some effects of a warming world can suppress hurricane formation by increasing wind shear, a rapid change in wind direction. But, once storms do form, the trend of warming oceans can make those storms more powerful and can cause them to intensify quickly. Higher sea levels contribute to greater storm surge, and, since a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, climate change is contributing to wetter storms.

Other research suggests that climate change is weakening the atmospheric currents that tend to move weather systems across the United States during the summer months, causing storms to stall and dump vast quantities of water on places, as was the case in Houston during Hurricane Harvey.

While climate change is clearly warming the oceans, Gerry Bell, the lead hurricane forecaster at NOAA, said that seasonal forecasters had chiefly looked to factors like El Niño and oceanic and atmospheric conditions — including the West African monsoon and multi-decadal cycles of hurricane formation — to determine what is likely to happen in coming months. The Atlantic is currently in a cycle of higher activity, he said, and those cycles “completely dominate the record.”

None of these forecasts can say whether the coming storms will make landfall, which can only be predicted about a week in advance. Still, “it only takes one storm to have catastrophic impacts on lives and communities,” Dr. Bell warned in a conference call with reporters. He recommended that coastal residents begin preparing for storms now, with hurricane information from the federal website Ready.gov.

The next storm names for the current season are Chantal, Dorian and Erin; if the prediction holds, the 17th storm would be Rebekah.

For more news on climate and the environment, follow @NYTClimate on Twitter.

8 August 2019

THE NEW YORK TIMES