No new oil, gas or coal development if world is to reach net zero by 2050, says world energy body

Governments must close gap between net zero rhetoric and reality, says International Energy Agency head.

Exploitation and development of new oil and gas fields must stop this year and no new coal-fired power stations can be built if the world is to stay within safe limits of global heating and meet the goal of net zero emissions by 2050, the world’s leading energy organisation has said.

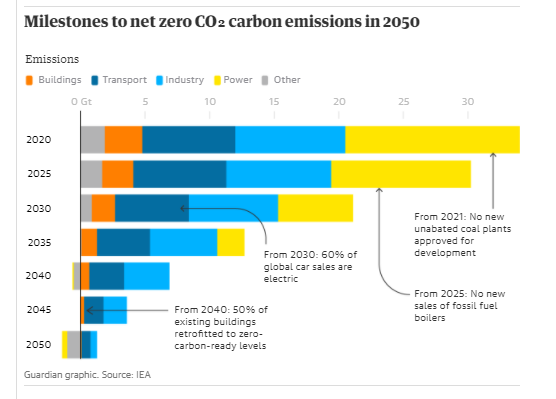

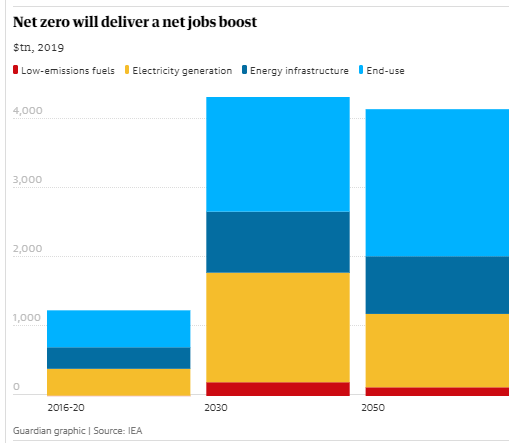

In its strongest warning yet on the need to drastically scale back fossil fuels, the International Energy Agency (IEA) also called for no new fossil-fuel cars to be sold beyond 2035, and for global investment in energy to more than double from $2tn (£1.42tn) a year to $5tn (£3.54tn) The result would not be an economic burden, as some have claimed, but a net benefit to the economy.

Fatih Birol, the IEA’s executive director and one of the world’s foremost energy economists, told the Guardian: “If governments are serious about the climate crisis, there can be no new investments in oil, gas and coal, from now – from this year.”

He said strong new policies were needed from governments around the world: “More and more countries are coming up with net zero commitments, which is very good, but I see a huge and growing gap between the rhetoric [from governments] and the reality.”

The IEA has released its most comprehensive report yet into what is needed to achieve the world’s climate goals, the implications of which will be felt around the world. Few governments intend to halt fossil-fuel exploration. The UK is licensing new oil and gas fields in the North Sea, China is building coal-fired power plants, and oil companies are still investing in new output.

Birol said they must reconsider. “Our report does not ban anyone from anything. If governments are planning investments, it is up to them. But if governments make commitments to net zero emissions, they should see what the implications are.”

Last month, the IEA warned that emissions would leap by the second biggest rise on record, largely owing to a resurgence of coal following last year’s lockdowns.

Pledges made by governments in the run-up to the Cop26 UN climate talks, due to be held in Glasgow this November, are also inadequate and need to be strengthened if the world is to limit temperature rises to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, he said. That limit, beyond which scientists predict dire consequences from climate breakdown, is the aspirational goal of the 2015 Paris agreement, and will require greenhouse gas emissions to be halved this decade.

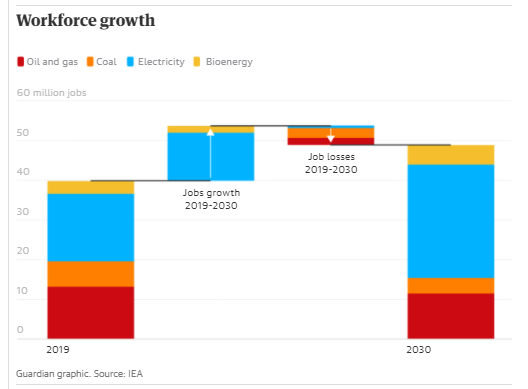

The report found that these measures would create 30m new jobs, and add 0.4 percentage points a year to global GDP growth. Birol said about 5m jobs would be lost in sectors such as coal, but governments could do much to ease the transition.

Birol said that the technology to halve emissions by 2030 was already available and must be rolled out even faster. “A huge part can be done with existing technologies, there are no problems there,” he said.

John Kerry, the US climate envoy, caused controversy when he suggested at the weekend that half of the carbon reductions needed to reach net zero by 2050 would be made using new technology. Climate experts including Michael Mann have become increasingly worried that some new critiques of climate action, such as the book published recently by the software billionaire Bill Gates, have focused too much on an idea that futuristic technologies will save the world from climate chaos, rather than focusing on what can be done today. Since the climate responds to cumulative emissions rather than current emissions, if cuts to carbon are left to the future and not made in this decade, it will be too late to stay within the 1.5C limit.

Birol made it clear that the technology needed to reach net zero is neither blue-sky nor futuristic. He said: “These technologies are already invented, but not yet in full development. Innovation is critical, but the technologies are here with us.”

The crucial new technologies in development are: advanced batteries, particularly for use in electric vehicles; hydrogen; and carbon capture.

These will be needed because some sectors are especially hard to decarbonise, such as steel and cement manufacturing, aviation and shipping, and those using heavy-duty road vehicles. Birol said that most of the rest of the global economy could be decarbonised using economical technologies that are already in widespread use, such as wind and solar power.

The IEA has set out 400 milestones for governments to reach, including the phasing out of new fossil-fuel cars from 2035 and the decarbonisation of global electricity generation by 2040. Its analysis also took into account a global population rise of about 2 billion people, as well as the need to supply electricity to 785 million people who do not have access to it, and clean cooking to the 2.6 billion people who currently lack it. Doing so would cost about $40bn a year, or 1% of global annual energy sector investment, and would cut premature deaths from indoor air pollution by about 2.5m a year.

The IEA undertook the report – the most comprehensive yet into the global requirements to meet the net zero emissions target – at the request of the UK government.

Alok Sharma, president-designate of Cop26 and a former UK business secretary, said: “We must act now to scale up clean technologies in all sectors and phase out both coal power and polluting vehicles in the coming decade. Our first goal for the UK as Cop26 presidency is to put the world on a path to driving down emissions, until they reach net zero by the middle of this century.”

The UK has begun the process of licensing new oil and gas fields in the North Sea and has also mooted a new coalmine for coking coal. Birol said that governments should consider what would happen to future demand and whether they might be left with stranded assets in the future.

He added that the IEA predicts that global oil demand will decline from the 90m barrels a day at present to about 24m barrels a day by 2030. “Therefore there will not be a need for new investments in oil and gas fields, or new investments in coalmines,” he said. “It depends how governments take climate change seriously.”

18 May 2021

The Guardian