Meltdown: the climate crisis – in pictures from the Natural History Museum of Vienna.

MELTDOWN – a visualisation of climate change has opened at Natural History Museum of Vienna. Created by the climate crisis charity Project Pressure, the exhibition on vanishing glaciers uses art to inspire action and behavioural change. Unlike wildfires, flooding and other weather events, the retreat of the world’s glaciers can be attributed to global warming. To incite action, Project Pressure has created a carbon footprint calculator in collaboration with ClimateHero to learn how carbon-intense the users’ lifestyle is.

Richard Mosse used a plate-film camera to photograph the ice cave under the Vatnajökull glacier in Iceland. Glacier caves form when warm air enters where water flows underneath the ice. The process is becoming more unpredictable because of rising global temperatures, which may lead to the cave becoming inaccessible

Photograph: Richard Mosse/Courtesy of Project Pressure

Edward Burtynsky shows us how humans are reshaping the Earth. The image of the vast Icelandic landscape depicts the beauty and monumental scale of the meltwater runoff with hints of manmade features. Burtynsky reminds us that we are losing a vital source of fresh water as glaciers continue to retreat across the globe

Photograph: Ed Burtynsky/Courtesy of Project Pressure

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin show how the shrinking glaciers are revealing artefacts which, until now, have been preserved for thousands of years. The pair’s work, created in collaboration with archaeological institutions and glaciologists in Switzerland, hints at intimate and complex human stories buried inside the ice

Photograph: Broomberg & Chanarin/Courtesy of Project Pressure

Klaus Thymann seeks to challenge conceptions of where glaciers exist, emphasising the importance of treating the climate crisis as a global issue rather than just one centred on the Arctic and Antarctica

Photograph: Klaus Thymann/Courtesy of Project Pressure

Scott Conarroe studies the boundaries devised by Alpine nations which are moving as a result of rapid melting of glaciers. The terrain itself shifts, resulting in a new topography that could require borders to be redrawn, leaving a question of territorial claim and possible geopolitical consequences

Photograph: Scott Conarroe/Courtesy of Project

Christopher Parsons joined forces with a research team to study glaciers and permafrost in the Sagarmatha region of the Himalayas. Samples were cultured and analysed by a microbiologist, and revealed the microbiological dynamics and organisms in the glacier environment that are invisible to the naked eye. Parsons displays these microscopic elements alongside the Nepalese landscape, offering the viewer multiple perspectives of the life sustained by the mountains and water, underlining the need for preservation

Photograph: Christopher Parson/Courtesy of Project Pressure

Adam Hinton’s 8-minute film shows the social impact of the climate crisis. He visits farming communities in India which depend on water runoff, showing the environmental effects on people’s lives. Unstable weather patterns are resulting in diminished crops, hunger and migration. Hinton tells the story of six families, but more than 1 billion people rely on water from the Himalayas

Photograph: Adam Hinton/Courtesy of Project Pressure

Noémie Goudal constructed a large-scale photographic installation printed on biodegradable paper that disintegrates in water. As the image dissolves, the artificial landscape can be viewed against its natural form, functioning as a reminder of the instability of the seemingly stable as well as a visualisation of the accelerating transformations in nature

Photograph: Noemie Goudal/Project Pressure

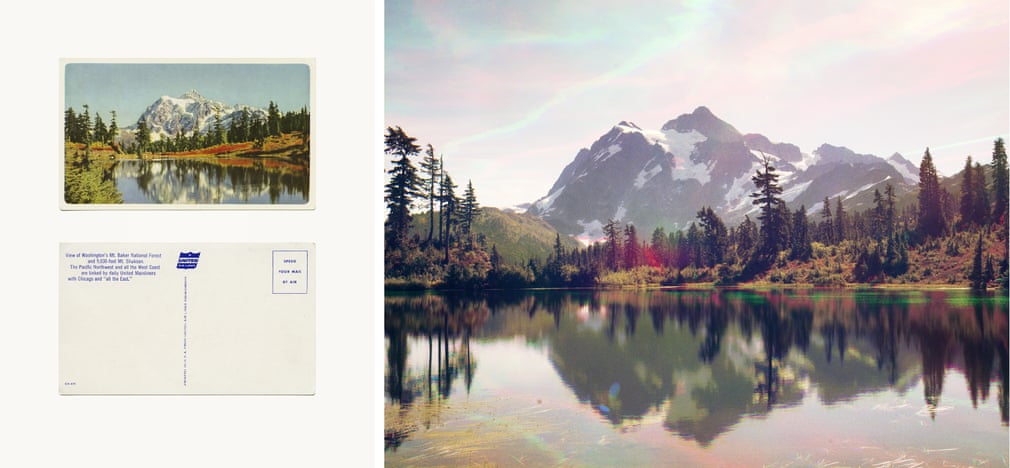

Peter Funch uses vintage postcards as a model for his images of Mount Baker in Washington state to capture the effects of glacial retreat. These effects are highlighted through his use of RGB tricolour separation, in which individual colour layers are recorded separately and then merged into a single image

Photograph: Peter Funch/

Over a three-week period in September 2013, Corey Arnold travelled around the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard. Glacial ice has been documented in the Hornsund fjord since 1899, and with the current changes in the Arctic, Arnold’s work functions as a reminder of the relation between the climate crisis and rising sea levels

Photograph: Corey Arnold/Courtesy of Project Pressure

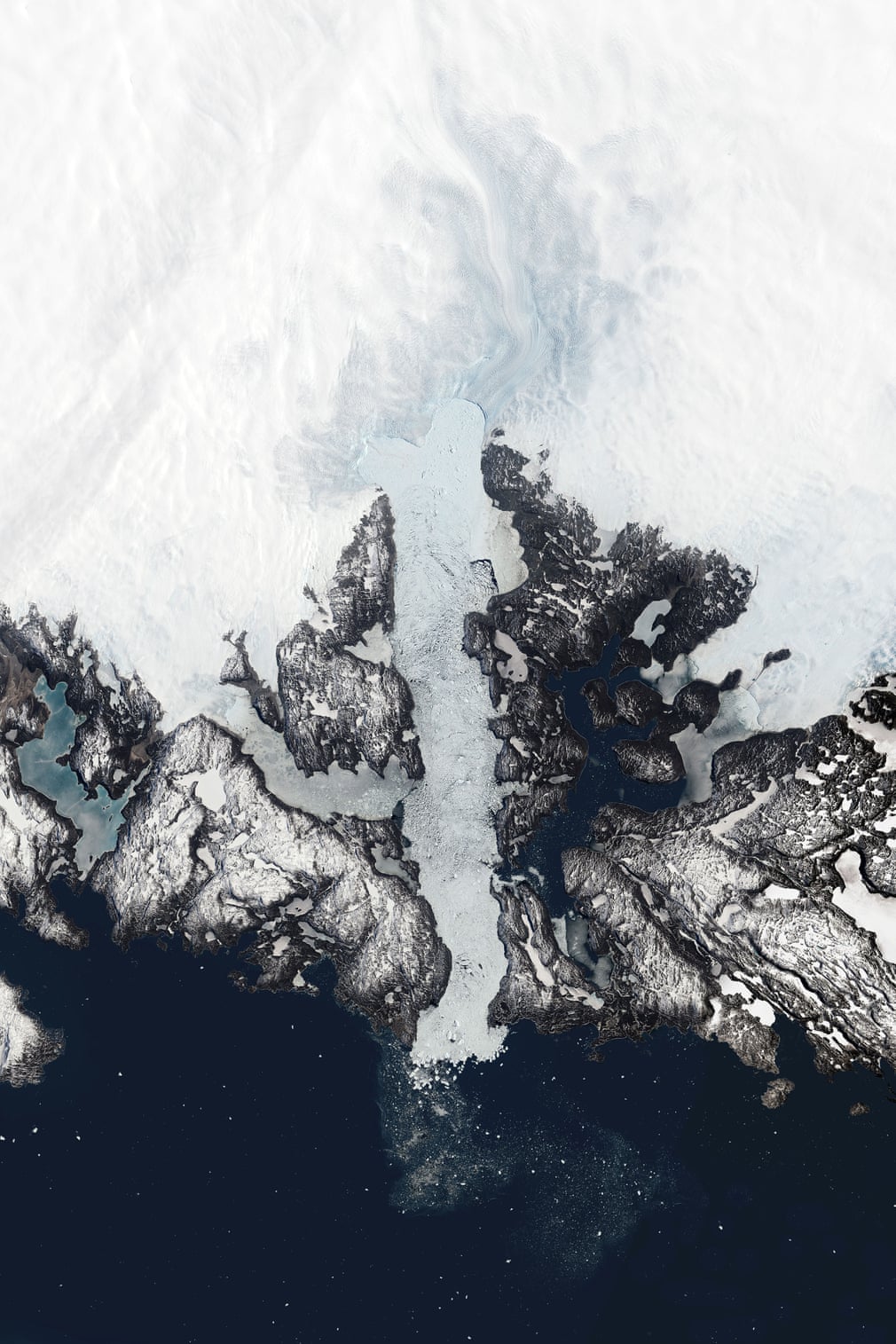

Michael Benson’s work is focused on the intersection of art and science. By using a variety of image-processing techniques, he takes raw data from planetary science archives and processes, edits and composites it. Benson uses this methodology to take this data, as well as satellite imagery of Antarctica’s ice fields, and translate it into planetary landscape photography

Photograph: NASA/Michael Benson/Kinetikon Pictures/Courtesy of Project Pressure

Toby Smith has created a documentary that shows the way the climate emergency is affecting the community who reside on a four-peak volcanic massif in Armenia. Analysis in recent decades has shown that the glacier’s surface area has retreated since the 1950s

Photograph: Toby Smith/Courtesy of Project Pressure

Simon Norfolk and Klaus Thymann address financial issues as driving forces behind human adaptation to the changing climate. The title Shroud refers to the melting glacier under its death cloak. In addition, a thermal image time-lapse film was created, showing how glaciers compare to the surrounding landscape by only reacting to long-term temperature changes, as opposed to weather fluctuations

Photograph: Simon Norfolk & Klaus Thymann/Courtesy of Project Pressure

Sourcing images from 1946, 1959, 1980 and 2017 of the Tarfala valley and Kebnekaise mountain in Sweden, Erwin van den IJssel, Erik Schytt Holmlund and Klaus Thymann developed a new way of visualising historic change throughphotogrammetry. As the video progresses into more recent times, the devastating effect humans continue to have on the melting glacier landscape is undeniable. In 2018 the highest point in Sweden changed: excessive heat in 2018 melted the south peak of Kebnekaise so the north peak is now Sweden’s highest point

Photograph: Erwin van den IJssel, Erik Schytt Holmlund and Klaus Thymann/Project Pressure

19 June 2019

The Guardian