Business groups say natural-gas delivery has reached a crisis point

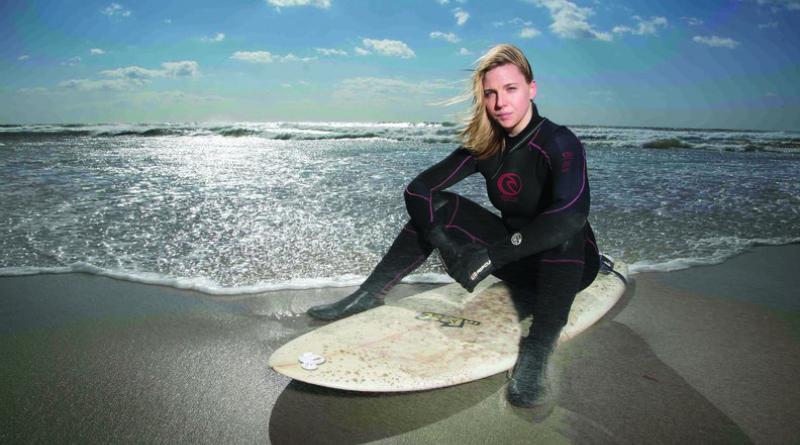

New York is a city of canyons. But for Ashley Fallon, a child of Breezy Point who now lives in Rockaway Beach, her portion of Queens can seem closer to California than Manhattan.

The view from her surfboard might include any of three species of whales, two kinds of dolphins and baby seals. Walking on the beach, she sometimes spots the rare snowy owl.

Fallon knows the beach was not always this clean or the water this full of life. That is one reason she has joined a coalition of local civic and environmental groups fighting the proposed Williams Transco natural gas pipeline. The groups, including Surfriders Foundation, 350.org and the Rockaway Beach Civic Association, insist the pipeline could inflict lasting environmental damage on the area.

The 24-mile expansion of existing pipeline infrastructure would run 17 miles underwater, from New Jersey's Raritan Bay across lower New York Bay to a Transco pipeline already in place three miles offshore from the Rockaway Peninsula. The projects supporters are no less passionate than Fallon. They say the Northeast Supply Enhancement Project, or NESE, will address a looming natural gas shortage in Brooklyn and Queens and on Long Island that could inflict lasting damage on the region's economy.

The battle is playing out amid another gas shortage that has raised alarms across the region's business community: Con Edison has declared a moratorium on natural-gas hookups in southern Westchester. As of March 15, the utility said, it will not be able to guarantee service for new projects, effectively stifling developments.

National Grid, Williams' partner in the NESE project, is warning of a similar moratorium in Brooklyn and Queens and on Long Island should New York not approve the billion-dollar pipeline by May 15. The state's Department of Environmental Conservation, which is weighing public comments, could block the pipeline if it found the project does not comply with the state'.

Both the utility and the pipeline developer say the project poses minimal environmental risks and will reduce carbon emissions by allowing customers to stop using oil. They have the staunch backing of labor and business groups; both view the pipeline as critical to growth, not to mention a source of construction jobs.

But environmental advocates aren't their only adversary: Gov. Andrew Cuomo has long been cool to fossil-fuel projects.

"We are fully committed to meeting this administration's nation-leading renewable energy goals while at the same time pushing utility companies to use existing infrastructure more efficiently," said a spokesman for the state's Public Service Commission, which helps set energy policy. "Major commercial projects can move forward without new infrastructure development."

Stifling growth

The arguments over the Williams pipeline have gone back and forth for nearly three years.

Natural gas was not supposed to be controversial.

But the cleanest-burning fossil fuel, once considered a bridge to a low-carbon future, increasingly has come under attack, as have the pipelines that deliver it.

Environmentalists have challenged the fuel's green reputation, saying when the entire process of extracting, transporting and burning natural gas is considered, its impact on climate change is no less severe than oil or coal. They point to the methane that is released into the atmosphere at various stages, including leaks through pipelines and during extraction by fracking. They have won—and sometimes lost—several court cases over environmental assessments that did not address the full scope of greenhouse gas emissions.

Opponents of the Williams project say that fuel shortages can be addressed through greater energy efficiency, and that the growing availability and dropping prices for renewables will soon make the project a white elephant. They maintain that the federal agency overseeing its development has not considered all alternatives, as is required under the National Environmental Policy Act, a failure that could expose the project to lawsuits.

National Grid, which supplies natural gas to 1.8 million customers in Brooklyn and Queens, on Staten Island and Long Island, says the need for the pipeline is unquestionable. It would increase capacity by 14%, delivering 400 million cubic feet of natural gas per day, and curtail the price spikes during cold snaps that push some large customers to switch temporarily to oil.

The utility, which hopes to have the pipeline in operation by the winter of 2020, says the region will suffer without it. It has begun informing developers of major new projects that it cannot guarantee uninterrupted gas service unless the NESE project goes through.

"We have told about two dozen of our largest customers we cannot commit to that supply," said John Bruckner, National Grid's New York president, pointing out that those service guarantees need to be locked in for several decades.

Alerted customers include the state's $1 billion redevelopment project at Belmont Park. Citing confidentiality, Bruckner declined to name any others, but he said they were spread around Brooklyn, Queens and Long Island.

And without the pipeline, large projects may be only the beginning.

"We'll have to go further into the market," Bruckner said of the potential moratorium to "midsize commercial projects and small businesses and eventually residential and oil-to-gas conversions."

Bruckner says that the NESE project aligns with the state's clean-energy goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80% from their 1990 levels by 2050. The pipeline, he says, will allow the company to continue converting 8,000 residential and commercial customers per year to gas from oil, displacing 900,000 barrels of heating oil each year and cutting carbon-dioxide emissions by 200,000 tons.

The utility is invested in solar energy, and it has connected Rhode Island's Deepwater Wind farm to the local grid. It is a partner with the city on its Newtown Creek renewable gas project, and it has taken part in energy efficiency initiatives and geothermal demonstration pilots.

But at this stage, Bruckner says, neither conservation nor renewable replacement can take the place of the pipeline in meeting the energy demand that National Grid expects will grow by more than 10% in the next decade.

"As we build out those new technologies, natural gas continues to be a solution and has already made a significant contribution to [emission] reductions," he said.

But the project's critics maintain the energy sector is at a tipping point, with new technology making strides in efficiency, and renewables having more potential. They cite gains from new boilers, building retrofits, eco-friendly building codes and more efficient electric heating and cooling systems.

They also point to the mounting debt and losses at energy companies that rely on fracking to extract oil and gas.

"You have to consider the alternatives now more than ever," said Tom Sanzillo, a former New York state deputy comptroller who is director of finance for the pro-renewables Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. "And the reason you have to do that is because conditions in the industry are changing so fast and there are more and more alternatives and innovations."

Troubled waters

Some foes see the project as not just unnecessary but dangerous.

"New York City spent billions of dollars to clean up this harbor," said Kimberly Ong, senior attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council. "It's the cleanest it's been in more than 100 years. This pipeline has the danger of taking us back in time."

Ong says the trenching for the pipeline will kick up more than 1 million cubic yards of sediment containing toxic heavy metals and PCBs. That could impede aquatic migration, clog fish gills, interfere with breeding and contribute to harmful algae blooms.

Williams, a Tulsa, Okla.–based pipeline giant that operates the Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line Co. known as Transco, notes that it has been making deliveries to New York City without incident since 1951. Modern construction methods, including use of a "jet trencher," would limit the churning up of sediment and have already been used for a recent 3-mile extension in the Rockaways without incident, the company said.

"The final environmental impact statement included a very robust analysis, with a lot of sediment computer modeling," said a Williams spokesman. "The results were that the plume [of sediment] would stay close to the ground and would not ultimately create an environmental hazard."

Indeed, the impact statement, released in January, found that the effect of contaminants on aquatic life would be "temporary and minor."

But environmental groups are often at loggerheads with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC, which prepared the report, and which they consider overly friendly to pipelines. The Natural Resources Defense Council points to long-term studies of pipeline construction that have shown fish populations were damaged for years—and notes that the impact statement isn't all rosy. It cites "direct and indirect impacts" along the path of construction (for both the proposed pipeline and the recent 3-mile extension) as well as in the wider area, including "mortality, injury, or temporary displacement" of organisms. There could also be "mortality of eggs and other life" from the stirred-up sediment.

The green group says pipeline safety is a real issue. Information compiled from public records and news reports by environmental organization 350.org, found 10 explosions or fires at Williams Transco pipelines and compressor stations in the past decade. In 2015 the company was fined $58,600 for not adequately inspecting transmission pipeline valves in New Jersey and New York City.

Williams says its safety record beats the industry average and it has learned from its mistakes.

"The incidents we've had have been very sobering," said Senior Vice President Scott Hallam. "We've put a lot of energy into understanding what the root causes were."

A spokesman noted that the final environmental impact statement deemed gas transmission pipelines safe and reliable, with a low risk of incidents at any one location across the more than 300,000 miles of pipelines in the United States.

The answer rests with the state's Department of Environmental Conservation, which must decide whether to issue the water quality certificate that will let the project proceed. The DEC, still collecting comments, set a public hearing for March 6 in Rockaway Park.

The Cuomo-appointed agency already has raised one key difference with the federal commission. In a letter to FERC in May in response to its draft impact statement, the department zeroed in on the study's failure to consider alternatives to the NESE project, specifically, using renewable energy and reducing overall demand.

FERC had dismissed those alternatives on what the state agency claimed were the "narrow" grounds that the project was designed to bring "incremental gas capacity" to National Grid. The DEC insisted that all the alternatives be considered in the final environmental statement.

But FERC maintained that "the purpose of the project is to transport natural gas." Renewables and reductions in demand "are not transportation alternatives," and, therefore, were not considered.

4 March 2019