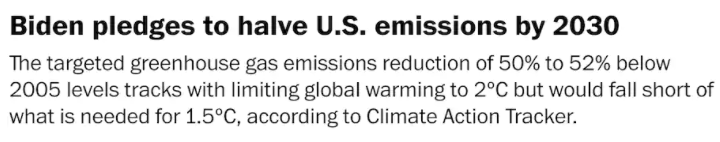

As Biden convenes world leaders, U.S. pledges to cut emissions up to 52 percent by 2030.

‘The stakes could not be higher,’ said one top administration official, as the White House presses other countries to make their own bold promises.

President Biden on Thursday will commit the United States to cutting its greenhouse gas emissions as much as 52 percent by the end of this decade, a pledge that would require fast and far-reaching changes to American life, from how people power their homes to the cars they drive.

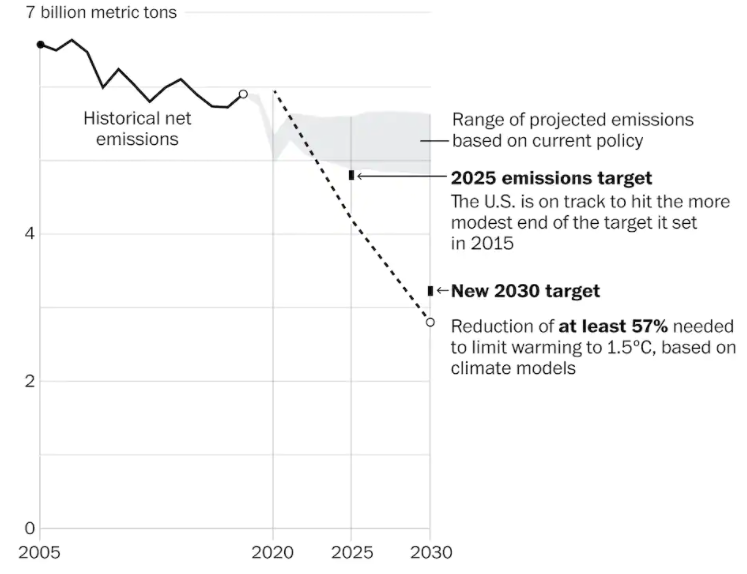

The highly anticipated announcement roughly doubles a target set by President Barack Obama in 2015 as part of the Paris climate accord, by vowing the nation will reduce its emissions between 50 and 52 percent by 2030 compared with 2005 levels. Biden plans to formalize the goal in a submission to the United Nations, the White House said.

The move comes as Biden convenes 40 world leaders for an Earth Day summit aimed at fueling similar ambition around the globe.

“Every country has to come to the table. … The stakes could not be higher,” said former secretary of state John F. Kerry, Biden’s special envoy for climate, in an interview with The Washington Post on Wednesday. “We hear people talk about this being existential. For many people on the planet, it already is. But we’re not behaving internationally like it is, in fact, an existential challenge.”

Only three months have passed since the United States, a driving force behind the Paris agreement, rejoined the accord after it became the only nation in the world to formally walk away from the pact under President Donald Trump. While numerous states, cities and businesses around the country pushed forward with efforts to scale back emissions and mitigate climate change, the federal government remained largely on the sidelines.

Biden’s renewed carbon-cutting pledge and the two-day White House summit are intended in part to reestablish U.S. leadership on international climate action and to kick-start momentum ahead of a key U.N. gathering this fall in Scotland, where nations are expected to arrive with bold new blueprints for how they intend to help slow the Earth’s warming.

“The ultimate measure of the Summit’s success will only become clear later this year, at the [climate] conference scheduled for November in Glasgow,” Nat Keohane, senior vice president at the Environmental Defense Fund, wrote in a blog post Wednesday. “The Biden administration has been in office fewer than 100 days, and diplomacy takes time; some of the administration’s efforts will undoubtedly only bear fruit in the coming months.”

Still, 85 percent of global emissions come from outside the United States, and the next two days could offer early glimpses about whether some of the world’s largest economies are ready to embrace similar promises and how bold they are willing to be.

Already this week, the United Kingdom on Tuesday announced plans to reduce its emissions by 78 percent by 2035, compared with 1990 levels — a goal the government said would take the nation more than three-quarters of the way toward reaching net zero by 2050. The European Union, meanwhile, has put forward a pledge to cut 55 percent of its emissions by 2030.

One major question mark remains China, the world’s largest emitter, which has pledged to reach net zero emissions by 2060, but it has yet to spell out the near-term actions it plans to take to begin altering its trajectory of greenhouse gas pollution. Previously, China said its emissions wouldn’t peak until 2030.

“Without China at the table, there is simply no way to resolve the climate crisis,” Kerry said Wednesday, noting that China is “the producer of almost half of the world’s coal-fired energy.” Kerry recently traveled to the country in hopes of fostering common ground on climate change, despite ongoing tensions with the United States over a range of other issues.

The world remains nowhere near meeting the central goals of the Paris agreement — namely, to limit Earth’s warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) compared with preindustrial levels, and if possible to stay closer to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Failure to hit those targets, scientists have warned, will result in a cascade of costly and devastating effects.

Biden’s plan to slash U.S. emissions at least in half compared with 2005 levels will not happen easily, or without help from Capitol Hill.

In its pledge Thursday, the Biden administration will not spell out precisely how it plans to meet the new target or how much individual sectors of the economy would have to reduce their emissions. Rather, the White House plans to detail the various sectors where it believes significant emissions cuts can happen in the years ahead.

“We see multiple paths to reaching this goal,” said one administration official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the plan had not officially been announced.

Much of that work includes policies Biden has previously identified: decarbonizing the power sector by 2035, boosting renewable energy technologies, electrifying millions of buildings around country, mandating more fuel-efficient cars and trucks, incentivizing sustainable agriculture practices and targeting emissions of methane, hydrofluorocarbons and other potent, short-lived climate pollutants.

Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.) has repeatedly urged the administration to set a specific target for cutting methane — which is released in drilling operations and from pipelines, landfills and dairy farms — because it can deliver significant near-term benefits.

The White House already is pursuing an all-of-government push to begin profound changes across the country in the way Americans live, work and travel. But hitting the new target will depend in part on whether Congress adopts a sprawling economic recovery package that includes extensive funding for clean-energy projects, green transit and climate-related research and development, as well as installing electric-vehicle charging stations from coast to coast.

The bill’s passage remains far from certain given Democrats’ razor-thin majorities in both legislative chambers. Some Republicans already have criticized Biden’s climate efforts as hasty and costly, and they argue that too rapid a transition away from fossil fuels could kill thousands of jobs in communities around the country that still rely on those industries. Some industry leaders also have warned of moving too quickly.

“Implementing policies that go beyond the capabilities of current technologies with unrealistic timeframes in the US [pledge] will only penalize consumers, our industry and our country’s energy security; further constrict the American economy when it is trying to recover; and cause job American losses everywhere from New Mexico to Pennsylvania,” Anne Bradbury, chief executive of the American Exploration and Production Council, a natural-gas trade group, said in a statement.

At the same time, the Biden administration has faced enormous pressure from environmental activists, Democratic lawmakers, foreign leaders and hundreds of private companies to make the boldest climate pledge possible. Most allies have praised the president for striving to cut at least half of the nation’s emissions by 2030, saying that science demands no less.

“President Biden has come through with a strong emissions reduction target that should make the world sit up and take note,” Manish Bapna, interim president of the World Resources Institute, said in a statement, calling the goal ambitious but attainable. “This target will serve as the North Star for President Biden’s domestic agenda. It will create a more equitable and prosperous society. At a time when the country is looking to bounce back from the pandemic, this goal will help unleash millions of good jobs, boost business and drive innovation.”

Biden is likely to face pushback Thursday from Republicans and some industries that say he is overreaching, though he could face criticism, too, from activists who argue that even the new pledge is far too paltry given the risks posed by climate change.

“A pledge to cut emissions 50% by 2030 simply isn’t big enough to meet the massive scale of the climate emergency,” Jean Su, the energy justice program director at the Center for Biological Diversity, said in a statement. “Solving the climate crisis requires applying both science and equity. On both counts, the U.S. — the largest historic polluter and one of the wealthiest nations — must do its fair share and cut domestic emissions by at least 70% by 2030.”

Evan Weber, political director of the youth-led Sunrise Movement, said in a statement that although the group appreciates Biden’s effort to ramp up climate action at home and overseas, so far he has fallen short.

“We have a responsibility to tell the truth: it is nowhere near enough,” Weber said. “The science is clear — if the U.S. does not achieve much, much more by the end of this decade, it will be a death sentence for our generation and the billions of people at the frontlines of the climate crisis in the U.S. and abroad.”

Steven Mufson and Juliet Eilperin contributed to this report.

22 April 2021

The Washington Post