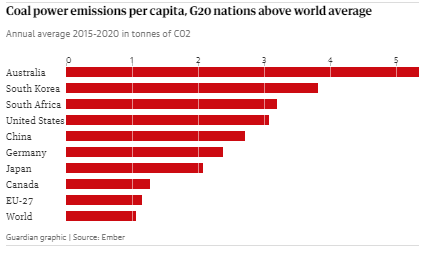

Australia shown to have highest greenhouse gas emissions from coal in world on per capita basis

Analysis released at Cop26 climate summit shows Australia’s per capita emissions from coal power nearly double those of China

Australia has the highest greenhouse gas emissions from coal power in the world on a per capita basis, nearly doubling those in China, according to a new analysis released at the Cop26 climate summit in Glasgow.

As the talks headed towards a fraught final day, there was disagreement over whether a closing declaration would commit countries to return with stronger short-term emissions reduction targets next year, and explicitly support an accelerated phaseout of coal.

The British climate and energy thinktank Ember released an analysis that suggested the world’s wealthiest countries remained among the worst emitters from coal power once population was factored in.

Australia topped the list, with annual per person emissions five times greater than the global average and 40% higher than any other major coal power user. Examining the period since the landmark Paris agreement was signed in 2015, the analysis found Australia emitted 5.34 tonnes of carbon dioxide per person each year, placing it ahead of South Korea (3.81), South Africa (3.19), the US (3.08) and the world’s biggest outright emitter, China (2.71).

Ember cited the International Energy Agency to argue OECD countries including Australia should end coal power by 2030 if they were to play their part in attempting to keep global heating to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels – a goal of the Paris agreement – within reach.

The Morrison government has rejected this and did not join a group of countries that pledged to phase out burning coal for electricity.

Dave Jones, Ember’s global program lead, said Cop26 had seen a divergence between developing Asian countries and major OECD coal users over the need to close coal generation. Vietnam had pledged to stop building coal plants and to stop using it in the 2040s, and Indonesia, the Philippines and India had shown signs they were changing previously held positions.

He said by comparison arguments put forward by Australia, Japan and South Korea were “embarrassing” and “simply untenable”.

“They will undoubtedly be forced to change their position in the coming months,” Jones said.

Ban Ki-moon, a former UN secretary general and deputy chair of The Elders, an international non-governmental organisation of senior statespeople, said the potential of renewable energy was growing exponentially and OECD countries needed to align with the target of phasing out coal entirely by the end of the decade. “This will be a true demonstration of global leadership,” he said.

About 60% of Australia’s electricity over the past year came from burning coal. That proportion is gradually diminishing and the country’s coal fleet is ageing, but under current closure schedules it would continue to use coal power until the late 2040s.

The Morrison government has been heavily criticised in Glasgow for its ongoing support of fossil fuels. Greenpeace International head Jennifer Morgan grouped it with Saudi Arabia as a “wrecker” opposed to the action needed to cut emissions and provide the finance needed to help developing countries respond.

Australia was one of only four countries, along with Indonesia, Mexico and Singapore, that chose to just resubmit the same 2030 emissions target at Cop26. Australia’s has committed to only a 26-28% cut compared with 2005 levels, though government projections suggest it could make a cut of up to 35%, in part due to state government policies. Scientists have advised global emissions need to be cut by 45% by the end of the decade.

Mary Robinson, a former president of Ireland and chair of The Elders, said leaders of developing countries were “in crisis mode” at the talks but some leaders who could do the most to address the problem were not. She bracketed Australia with Saudi Arabia, Brazil, China and Russia.

“Australia, a wealthy country, is still in fossil fuel mode, not in crisis mode,” she told the UK’s Sky News.

The talks were boosted late on Wednesday by a surprise joint declaration by the two biggest emitters, China and the US, that they would work together to cut emissions in the crucial next decade.

But there was significant disagreement between countries over a draft text released Wednesday morning.

It included a proposal that countries return to the negotiating table next year with new plans to ramp up emission cuts this decade. Under the Paris agreement, countries are expected to return with better pledges in 2025 but - with a chasm between existing commitments and the deep cuts needed - many are now demanding the deadline should be brought forward.

The draft text also proposed countries agree to accelerate the phasing out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels.

Australia has not been represented at a political level at the talks since Angus Taylor, the emissions reduction minister, left a week ago, and it has not made public its position on key parts of draft text released on Wednesday morning. But Scott Morrison has previously strongly opposed suggestions coal power should be actively phased out, and said he has no plans to increase Australia’s 2030 commitment.

In a statement on Thursday, Taylor said Australia was “an active and constructive participant in the negotiations to ensure a positive outcome”.

There is dispute between countries over whether the text will keep a reference to the scientific case for limiting global temperature rises to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, with some large developing countries reportedly opposed. Poor countries said much more needed to be done to increase finance packages to help them cut emissions and cope with the impacts of climate breakdown.

Scientists at the talks expressed frustration that rhetoric from global leaders was not being matched by action, and warned that every extra fraction of a degree of global heating would have dire consequences.

11 November 2021

The Guardian