And then there were two: can northern white rhinos be saved from extinction?

There are only two remaining rhinos of this species, a mother and daughter, but scientists see new hope in stem cell breakthroughs

“Iwatch these beautiful animals walk the path toward extinction every day,” keeper James Mwenda tells me. He’s out in the Kenyan bush, swatting flies. The anti-poaching K-9 dogs bark in the background. “I’ve watched their numbers fall from seven to two ... Working with them and watching what’s happening – it’s an emotional freefall.” He smiles, clearly resigned to the pain of bearing witness. “But I’ve dedicated my life to it.”

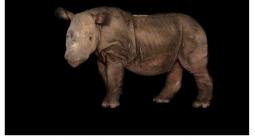

The window to keep the northern white rhino from going functionally extinct to fully extinct is closing fast. Were things left only to nature, the two remaining rhinos – elderly, calm Najin and her feisty 20-year-old daughter Fatu – would be the last of their kind to graze the African grasslands. After civil war, habitat loss, and aggressive poaching, scientists declared the species extinct in the wild in 2008.

Scientists now have a last-minute chance to bring the northern white rhinos back from the void, thanks to stem cell breakthroughs – but only if they can manage to work through the constraints of the pandemic.

“In 2012, there was no hope for the northern white rhino,” Dr Thomas Hildebrandt, a Berlin-based expert in wildlife reproduction, tells me. But, inspired by an interdisciplinary conference on interstellar life, Hildebrandt used grant money to forge an international consortium dedicated to saving the species. “We realized we were not yet at the end. There was, suddenly, a new horizon.”

He spearheaded “BioRescue” – a collaboration between the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, the Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic, Italian laboratory Avantea, and Kenya’s Ol Pejeta and Kenya Wildlife Service. Hildebrandt believes increased international cooperation is the future of conservation, sharing resources without the expectation of payback. “It’s the moral thing to do,” he says.

Covid-19 thwarted BioRescue’s 2019 momentum, disrupting travel and diverting science funding. They wondered if they would be able to harvest more egg cells from Fatu and the aging Najin and get them to a laboratory in Italy during a global pandemic.

But given the cost and complexity – should they?

How we answer this question not only determines the rhinos’ future, but our ability to pioneer processes that will be called upon to preserve other species.

•••

The stakes could not be higher. There are no longer any living northern white rhino males after the beloved Sudan was humanely euthanized at the advanced age of 45 in 2018. Ol Pejeta employs intense security measures against the constant threat of poaching: armed rangers, electric fences, the specialized K-9 unit, motion sensor cameras, and airplane surveillance.

In 2014, scientists discovered that 20-year-old Fatu cannot conceive naturally, and recently that her mother Najin has a large tumor in her abdomen next to her left ovary, potentially compromising the egg harvesting process. Najin’s hind legs are weak and veterinarians believe a pregnancy – 16 months of depleted resources for the mother and a 100kg baby – would cause debilitating stress.

In December, BioRescue harvested 14 egg cells from Fatu using an ultrasound-guided probe. Though sperm can be frozen, unfertilized eggs cannot. Thus, Fatu’s eggs are better traveled than any of us in 2021. They were overnighted via a charter flight from Nairobi to Frankfurt to Milan, then driven to the Avantea laboratory in Cremona, Italy.

Once in Italy, Fatu’s eggs were matured and combined with frozen sperm from Suni, a bull born in 1980. (Though he died of natural causes in 2014, Suni’s sperm was collected when he was still relatively young. His sperm is considered healthier than that collected from the aged Sudan.) After eight of Fatu’s eggs were fertilized, two were deemed viable, and were cryofrozen on Christmas Eve, bringing the total frozen embryo count to five.

Though Suni is dead and Fatu cannot conceive, science has christened this couple the future of the northern white rhino.

•••

In November 2015, I joined an NGO focused on ending extreme poverty for women in Nanyuki, Kenya. Before heading to our field work further north, we drove into the Ol Pejeta Conservancy after a brief but violent rainstorm. There, I witnessed the last remnants of several species: a handful of Grevy’s zebra, a reticulated giraffe, a cheetah, and – just beyond an electric fence and armed guards - the last three northern white rhinos. Sudan was still alive.

I walked through Ol Pejeta’s rhinoceros cemetery, where a sign reads: “A Memorial to Rhinos Poached on the Conservancy Since 2004.” I stood next to a gravestone for Shemsha, a female black rhino who was “shot dead with both horns removed”. Rhino poachings are gruesome, calculated and a daily danger for both the rhinos and the rangers.

That November, I photographed Sudan and Najin in their 700 acre enclosure. Now the photos remind me of those of the last passenger pigeon named Martha, or the last Carolina Parakeets named Incas and Lady Jane. When populations dwindle, a specificity occurs. A personal connection blooms, making investment more urgent, and the loss harder to bear.

Mwenda thought he would leave his job as a keeper at Ol Pejeta after Sudan died. “No one wants to be associated with failure,” he says. “No one wants to watch a species die.”

Mwenda recalls a day three years before Sudan was euthanized. “I was standing with him out in the field, feeding him bananas. I enjoyed looking at his lovely face. I think he was feeling good. But then I looked at him and saw he was dropping tears. I know scientists will say that rhinos do not cry. But I think maybe he was feeling empty. I laid my hands on him. After that day, I decided it was not about taking selfies with rhinos and making a photo about the last of a species. It’s about making meaning. I told Sudan I would become his voice when he was gone.”

Mwenda thinks a lot about the youngest rhino, Fatu. Soon, her mother Najin’s age and tumor will lead to a decline. “Fatu is an ending,” Mwenda says. “This is her reality. She will have to bear the responsibility of being the last of her kind. She will be a symbol of political and human greed. That’s what her loneliness stands for. That is her work.”

•••

BioRescue must balance short term objectives – like extracting eggs and freezing embryos – with ambitious long-term plans.

“We plan to have a calf on the ground in two to three years,” Hildebrandt tells me.

First, scientists will plant Suni and Fatu’s embryos into a southern white rhino female, a similar rhino which diverged from the northern white rhino around a million years ago. Owuan, a sterilized southern white bull, arrived at the conservancy in early December to help indicate when the female is in heat, maximizing chances that the embryo will take.

Luckily, frozen embryos are not the only path forward. Nobel Prize-winning scientist Shinya Yamanka’s work with mice shows that skin cells can be transfigured with stem cells to create gametes – or, as the everyday reader might think of it: test tube rhinos. According to Hildebrandt, enough skin cell samples exist to create the necessary genetic diversity for a healthy future population. Over 20 to 30 years, the population would grow in surrogates and sanctuaries. One day – perhaps when Fatu and the original scientists are gone – northern white rhinos will return to Uganda, the most feasible country in the rhino’s original range.

The embryos are currently stored in a tank of liquid nitrogen kept at -196C, with a backup generator for additional security. Theoretically, the embryos will continue to be viable for thousands of years, waiting for science to catch up.

“Liquid nitrogen buys us time,” Hildebrandt says.

I think of Norway’s Svalbard Global Seed Vault, or as some call it – the Doomsday Vault. I imagine the analogous sperm and oocyte bank of endangered species, a frozen Noah’s Ark, where embryos from Fatu and Suni join embryos from vaquitas, cheetahs and Right Whales. A so-called Bio Bank.

But liquid nitrogen cannot replace what Hildebrandt calls “social knowledge”. It’s critical that a baby northern white rhino spend time with Fatu and Najin to learn the proper head position for grazing. “A southern white rhino can provide a northern white rhino milk,” Hildebrandt says. “But not species-specific knowledge.”

•••

How do we determine which species are worth saving, and how far to go? How do we realize when we’re pushing western conservation standards and consequences on other nations – like punishing hungry locals hunting animals for bush meat, or asking them to change longstanding cultural beliefs and medicinal practices? Is conservation a global concern? These are questions that will be asked increasingly as the planet hurtles through its sixth mass extinction.

I ask BioRescue if, ethically speaking, there’s a way the conservation community thinks about prioritizing spending to prevent extinction. For example, do we prioritize animals who have an important function in their ecological niche?

Hildebrandt points out that preserving the integrity of keystone species and ecosystems is a public health issue. “We may get more pandemics as systems break down,” he notes, thinking about HIV, Ebola, Covid, and ones we can’t yet imagine. Unhealthy and unnatural ecosystems release pathogens and promote the spread of disease.

“This is not just exotic conservation or a scientific exercise, like the mammoth project,” Hildebrandt explains, “but an attempt to repair a complex ecosystem. We are providing solutions for irresponsible behavior. It is much wiser to save species through responsible behavior, while we still can.”

“Think of all the other ridiculous things humans spend money on. This may be cheap in comparison,” Jan Stejskal, director of international projects for the Dvůr Králové Zoo, tells me.

“I believe in the value of the rhino himself,” Stejskal adds. “Who can ascribe value to an animal? It’s about more than subsistence. It’s deeper than that.”

“It’s existential, a new philosophy,” Hildebrandt says. “Sudan is not dead for me. What is death? He is saving his species. This is life. It’s a complex process, but it’s possible to preserve life, and give opportunities to future generations.”

Mwenda hopes that the upside of Covid’s impact on tourism is that Kenyans have been able to connect with wildlife through opportunities usually reserved for tourists. He wants Kenyans to see the northern white rhinos as not just good for tourists, but good for Africa.

“These rhinos are my family,” Mwenda says. “I spend more time with them than my own family. I truly love them.” His shift is winding down as we finish our talk. Soon, he will escort Najin and Fatu to their evening enclosure, his favorite time of day.

“Right now it sounds helpless,” Hildebrandt says. “But we have a fair chance. We just need support. The fragility of our planet is dramatic. We must act now.”

14 January 2021

The Guardian