Bacteria helping to extract rare metals from old batteries in boost for green tech

Workers sorting electronic waste at a factory in India. Photograph: Elke Scholiers/Getty Images

Scientists have formed an unusual new alliance in their fight against climate change. They are using bacteria to help them extract rare metals vital in the development of green technology. Without the help of these microbes, we could run out of raw materials to build turbines, electric cars and solar panels, they say.

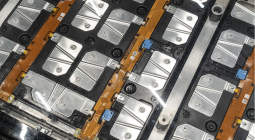

The work is being spearheaded by scientists at the University of Edinburgh and aims to use bacteria that can extract lithium, cobalt, manganese and other minerals from old batteries and discarded electronic equipment. These scarce and expensive metals are vital for making electric cars and other devices upon which green technology devices depend, a point stressed by Professor Louise Horsfall, chair of sustainable biotechnology at Edinburgh.

“If we are going to end our dependence on petrochemicals and rely on electricity for our heating, transport and power, then we will become more and more dependent on metals,” said Horsfall. “All those photovoltaics, drones, 3D printing machines, hydrogen fuel cells, wind turbines and motors for electric cars require metals – many of them rare – that are key to their operations.”

Politics is also an issue, scientists warn. China controls not only the main supplies of rare earth elements, but dominates the processing of them as well. “To get around these problems we need to develop a circular economy where we reuse these minerals wherever possible, otherwise we will run out of materials very quickly,” said Horsfall. “There is only a finite amount of these metals on Earth and we can no longer afford to throw them away as waste as we do now. We need new recycling technologies if we want to do something about global warming.”

And the key to this recycling was the microbe, said Horsfall. “Bacteria are wonderful, little crazy things that can carry out some weird and wonderful processes. Some bacteria can synthesise nanoparticles of metals, for example. We believe they do this as a detoxification process. Basically they latch on metal atoms and then they spit them out as nanoparticles so that they are not poisoned by them.”

Using such strains of bacteria, Horsfall and her team have now taken waste from electronic batteries and cars, dissolved it and then used bacteria to latch on to specific metals in the waste and deposit these as solid chemicals. “First we did it with manganese. Later we did it with nickel and lithium. And then we used a different strain of bacteria and we were able to extract cobalt and nickel.”

Crucially the strains of bacteria used to extract these metals were naturally occurring ones. In future, Horsfall and her team plan to use gene-edited versions to boost their output of metals. “For example, we need to be able to extract cobalt and nickel separately, which we cannot do at present.”

The next part of the process will be to demonstrate that these metals, once removed from old electronic waste, can then be used as the constituents of new batteries or devices. “Then we will know if we are helping to develop a circular economy for dealing with green technologies. New legislation has decreed that by the next decade recycled metals will have to be used at significant levels for manufacturing new green technology devices. Those goals will be hard to achieve and bacteria will be vital in achieving them.”