Big farmers use climate-resistant seeds. Most small farmers can’t get them.

Half of all humans owe their lives to small farmers, because that’s who grows most of the food in Africa and Asia. But it turns out that small farmers in poorer countries are stuck with seeds that can’t cope with a rapidly changing climate.

It’s a different story here in North America. A farmer in Illinois facing drought can plant Pioneer’s AQUAmax corn, which provides solid yields in dry years. If damp weather is covering your peas in powdery mildew, you can get mildew-resistant seeds. Most small farmers, on the other hand, can’t get their hands on new seeds bred to tolerate droughts, floods, and pests.

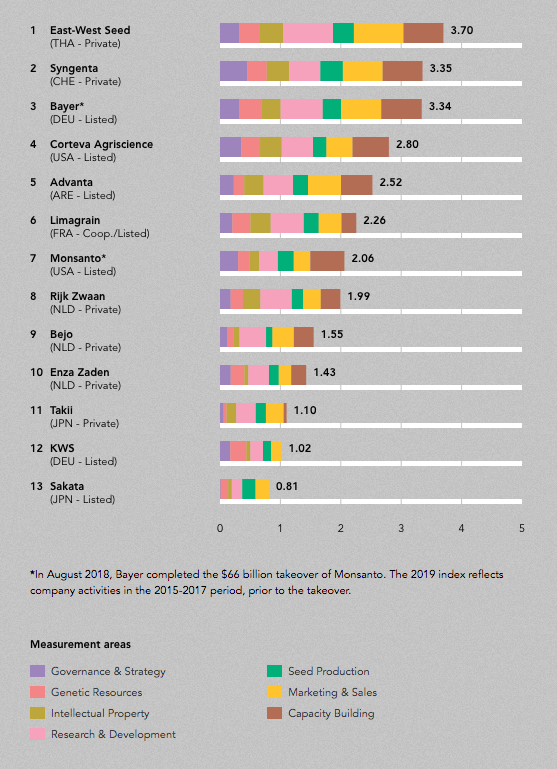

For the past six years, the Dutch nonprofit Access to Seeds has been researching the $50-billion seed industry — companies like Monsanto-buyer Bayer, Syngenta, and Pioneer — to see if they are making the latest innovations available to small farmers. It released a report this week showing that the vast majority of the world’s farmers can’t get their hands on the same seeds that help wealthier farmers produce bountiful harvests.

Grist spoke to Ido Verhagen, executive director of the nonprofit, about why more small farmers are seeking out improved seeds, why no one wants to breed beans, and why he thinks we need agribusinesses to help fix the food system. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Q. Why should we care if farmers are able to buy the latest seeds?

A. Seed is the key technology in agriculture. If we want Earth’s population of 10 billion by 2050 to have nutritious diets without ruining the planet we have to create a more sustainable food system, and that starts with seeds.

Q. I know some readers will think that companies selling seeds to small farmers would be a problem, not a solution.

A. I’m not claiming farmers should use seeds coming from companies, but I think they should have the choice.

There’s an Israeli NGO called Fair Planet seed that did some experiments with farmers in Ethiopia testing seeds from companies and traditional varieties. Just by using more advanced practices like using seedbeds [rather than throwing seeds across a field), they could double the yields of their traditional varieties. But by using varieties that were the result of modern plant breeding, yields were five times higher. So farming techniques matter a lot, but seeds matter even more.

Also, in times of climate change, more farmers are starting to ask for seeds. We did roundtable discussions with farmers’ organizations, and farmers from Africa said, “Yes, why can’t we get access to the technologies that are just common in Europe and the USA?” But farmers from Asia told us, “Well, actually we manage quite well ourselves.” We had these same roundtables just three years later in 2016 and everything had changed. Even the farmers in Asia were saying, “We do need better seeds because of climate change.”

The old method — farmers saving the seeds from the plants that perform best each season — was not keeping up with climate change.

Q. How many small farmers have that option?

A. The big global companies reach just 10 percent of small farmers. But there are smaller seed companies everywhere. I was impressed by the regional seed industry in Asia: They have broad breeding programs, they are highly competitive, and they are investing in a lot of local businesses. In East Africa, there is an emerging seed industry, but they only breed for a select few crops. If you include those smaller regional companies, they reach 20 percent of small farmers around the world.

![]()

Q. Are there crops that aren’t getting enough attention?

A. The seed industry hardly invests in legumes [like chickpeas, lentils, and beans]. That’s an issue.

Q. Yeah, if we want to get protein from plants rather than carbon-intensive meat, we need legumes.

A. Yes, but it’s difficult to build a business case for them. Their seeds are easy to reuse, so farmers don’t have to buy them every season. That means companies get a lower return on investment for all the breeding, so they aren’t as interested.

Q. One thing you found is that companies are starting to breed crops with better nutritional value.

A. For a long time in breeding, the focus was on yield and disease resistance, and nutrition wasn’t a priority. Now more and more seed companies tell us that nutrition is also a breeding target. But this is difficult and it can be hard to get farmers to adopt those seeds because they generally care more about yield, not nutrition.

Q. What happens next, ideally?

A. We started six years ago, more or less as a copycat initiative. There was already something called the Access to Medicine Index that wanted to encourage Big Pharma to make medicine available in developing countries. It created a race to the top, and increased the understanding between the public and private sectors, allowing, for example, the World Health Organization and pharmaceutical companies to form partnerships.

So our main goal is just to show how this industry is performing and which companies are good candidates for partnerships with NGOs and research institutes. If we want to be able to feed 10 billion people without exceeding planetary boundaries, the whole system has to move. And these benchmarks allow us to identify priorities.

Q. I know this is just your second report, but do you see any examples of companies reacting in a race-to-the-top kind of way?

A. I think you have to be modest — we can’t assume it’s because of us. But three years ago, only a few of these companies had really thought about how to contribute to global food security — at least not explicitly. Now almost all of them have explicit targets.

They are looking at their strengths and trying to use them. So a Dutch seed company that is really good in breeding is opening a breeding station in Tanzania. Syngenta has set up a foundation with projects around the world to help pre-commercial farmers adopt new technologies and start selling food. Companies are exploring how they can contribute, and not just by charity, because charity is good but it can start today and stop tomorrow. We are really interested in sustainable business models, so that the seed is there season after season for farmers.

1 February 2019

Nathanael Johnson

![]()