Why is support for nuclear power noisiest just as its failures become most clear?

The UK government and mainstream media agree we need nuclear to avoid the worst climate change. They’re wrong – so why aren’t we hearing that?

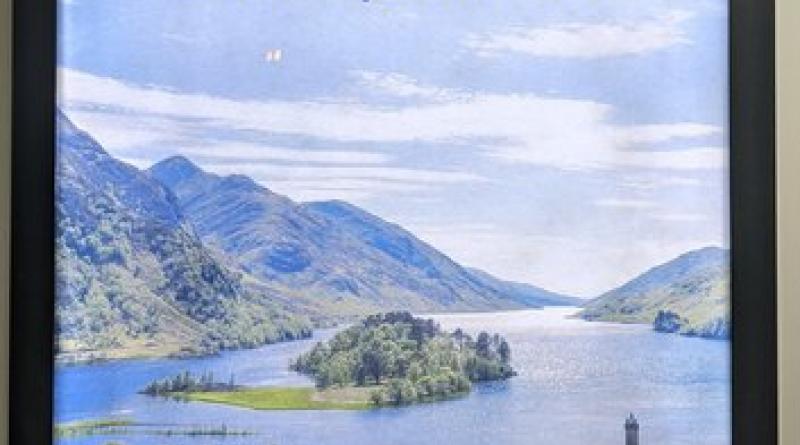

At Edinburgh’s Haymarket station, on the route used by COP26 delegates hopping across to Glasgow in November, a large poster displayed a vista from the head of Loch Shiel. In the foreground, a monument to the Jacobite rebellion towers from the spot where Bonnie Prince Charlie raised his standard. From there, the water sweeps back to a rugged line of hills.

This is one of Scotland’s most iconic views, famous for both its history and its role in the Harry Potter films.

On the poster, written in the sky above the loch are the words: “Keep nature natural: more nuclear power means more wild spaces like these.” At the bottom is a hashtag – #NetZeroNeedsNuclear – with no further mention of who might be behind this advert.

But it’s not hard to find a website for this group, which claims to be run by “a team of young, international volunteers made up of engineers, scientists and communicators”, all with the engagingly smiley profile pictures to be expected from citizen activists.

Only when you scroll to the end do you see these activities are ‘sponsored’ by nuclear companies EDF and Urenco. At the bottom, it is explained that Nuclear Needs Net Zero is part of the Young Generation Network (YGN) – “young members of the Nuclear Institute (NI), which is the professional body and learned society for the UK nuclear sector”. The website asserts that the Nuclear4Climate campaign – described as “grassroots” both on the site and in a presentation to an International Atomic Agency conference in 2019 – is in fact “coordinated via regional and national nuclear associations and technical societies”.

During COP26, Nuclear Needs Net Zero laid on a pro-nuclear flash mob in central Glasgow, complete with young dancers wearing ‘we need to talk about nuclear’ T-shirts. Such is the ostensibly fresh, youthful face of today’s nuclear lobby.

Of course, all this is par for the course in the creative world of PR. But there are more substantive grounds why nuclear advocates might wish to avoid too much public scrutiny at the moment. One reality, which can be agreed on from all sides, is that this is by far the worst period in the 70-year history of this ageing industry. So how come it is benefitting from growing and noisy support in mainstream and social media? Why are easily refuted arguments still being deployed to justify new nuclear power alongside renewables in the energy supply mix? And why has the media seized so enthusiastically on a few prominent converts to the nuclear cause?

Nuclear loses out to renewables

At current prices, atomic energy now costs around three times as much as wind or solar power. And that’s before you consider the full expense of waste management, elaborate security, anti-proliferation measures or periodic accidents. For more than a decade, nuclear has been plagued by escalating costs, expanding build times and crashing orders. Trends in recent years are all steeply in the wrong direction.

So the rising clamour of advocacy seems to be in inverse proportion to performance. Whatever view one takes, nuclear power is in a worse position than it’s ever been compared with low-carbon alternatives – and a position that is rapidly declining further.

Among those few countries still pursuing large-scale nuclear new-build programmes, most (like the UK) are either equipped with, or actively chasing, nuclear weapons. But even in the UK (home to one of the proportionally most ambitious nuclear programmes in the world), official data unequivocally shows that renewable energy seriously outpaces nuclear power as a pathway to zero-carbon energy.

Why are easily refuted arguments still being deployed to justify new nuclear power?

In fact, despite misleading suggestions to the contrary by senior figures, background government data has for decades shown that the massive scale of viable UK renewable resources is clearly adequate for all foreseeable needs. Even with storage and flexibility costs included, renewables are available far more rapidly and cost-effectively than nuclear power.

So, for all the breakdancing, it really is a conundrum why persistently bullish government and industry claims on nuclear power remain so seriously under-challenged in the wider debate. It is becoming ever more clear that nuclear plans are diverting attention, money and resources that could be far more effective if used in other ways.

One impact of this continuing official nuclear support is that climate action is being diminished and slowed. As a paper in Nature Energy (which one of us co-authored) showed last year, in worldwide data over the past three decades, the scales of national nuclear programmes do not tend to correlate with generally lower carbon emissions. The building of renewables does.

In fact, this study found “a negative association between the scales of national nuclear and renewables attachments. This suggests nuclear and renewables... tend to crowd each other out.”

The issues are, of course, complex. But this finding supports what the dire performance picture also predicts: that nuclear power diverts resources and attention away from more effective strategies, increasing costs to consumers and taxpayers. So it is even odder that loud voices continue to make naïve calls to ‘do everything’ – that nuclear must on principle be considered ‘part of the mix’ – as if expense, development time, limited resources and diverse preferable alternatives are not all crucial issues.

Despite the urgency of the climate emergency, there is strangely little discussion about this evidence that nuclear power may be impeding progress with options that clearly work better.

The media loves nuclear power

In fact, the British media has developed a habit of doggedly repeating claims by the nuclear industry that are, at best, somewhat wishful thinking.

One would not guess from all the noise about ‘small modular reactors’ (SMR), for instance, that the record of new nuclear designs has consistently been one of delayed schedules and escalating prices. One might easily miss that efforts at nuclear cost reduction have always depended more on scaling up than scaling down. And new SMR programmes do not even claim to address pressing current carbon targets. With debate persistently dominated by naively optimistic projections, it is oddly neglected that these familiar claims and sources have all repeatedly been falsified in the past.

Likewise, UK media debate remains unquestioningly locked into sentimental attachments to old ideas of ‘base load’ nuclear power – a notion now recognised by the electricity industry to be outdated. Far from being an automatic advantage, the inflexibly steady ‘base load’ output of a typical nuclear power reactor can present growing difficulties in a modern dynamic electricity system. It often seems to be forgotten that frequent unplanned nuclear closures pose their own kinds of intermittency risks, made worse by the massive unit sizes of nuclear reactors.

In fact, smart grids and plummeting storage costs make the challenge of managing fluctuating renewable energy sources far less significant than the growing price advantage enjoyed by renewables over nuclear power. Yet the variable outputs of renewables continues to be raised as an issue in the UK, as if this were some kind of trump card, as though two decades of technological advance never happened.

Points are further routinely missed when media attention is repeatedly given to emphatic claims that relatively few people died directly during nuclear catastrophes like Chernobyl and Fukushima. This surprisingly neglects the fact that – whatever position one takes on their magnitude – the real public health risks from these major releases of radioactivity lie in a generally elevated incidence of cancer, not in people falling dead on the spot.

It is against this substantive background that the persistent intensity of UK government support for nuclear power is so odd – and the rising clamour of UK pro-nuclear PR and media articles so striking. Nor is it just the media. Among campaigners, it is strange, given resolute government nuclear commitments, that even some of the previously most critical voices (like Friends of the Earth), seem to be growing strangely quieter.

Environmentalists’ Damascene conversions

One oddly prominent trope pertains to environmentalists who are reported to have changed their minds. In any time, such personal shifts would generally be a peculiar media preoccupation – no other debate in the environmental movement is closely followed in the establishment press. But when the reported changes so consistently favour such a manifestly globally failing policy, it is especially peculiar. Why, when nuclear fortunes are at their lowest ebb in half a century, is the surface impression so much more supportive than it ever has been?

For instance, some of the most prominent examples of the ‘repentant critic’ trope emerged a decade ago, around George Monbiot and Mark Lynas. Each has emphasised repeatedly and loudly that they were once actively critical of nuclear power, but have since changed their thinking to become more favourable.

Speaking to openDemocracy, Monbiot this month clarified that he is against Hinkley C nuclear power station in Somerset, due to open in 2026, which he called “a white elephant”. But – despite the issues around SMRs mentioned above – he says he “remains enthusiastic about fourth generation modular technologies [like many SMRs]”.

Crucially for Monbiot: “Fukushima woke me up to how low the risk from nuclear was by comparison to other energy sources. A disaster on such a scale… and nobody died. Yet, as a result of it, several governments started talking about scrapping their nuclear power stations, which meant returning to fossil fuels. Germany went all the way, with catastrophic consequences: early decommissioning meant hundreds of millions of tonnes of extra CO2. Because of what? The risk of tsunamis in Bavaria?”

For his part, Lynas told openDemocracy: “I think the anti-nuclear side are the ones accepting a few extra billion tonnes of CO2 in order to get zero-carbon nuclear fission off the grid!”

Of course, it is a strength, not a weakness, to be able to change one’s mind. And free thinking should always be welcomed. It might be wondered why Lynas and Monbiot’s changes of views run counter to trends in the relative performance of nuclear power. We might wish they would engage more with some of the substantive developments summarised earlier in this article, but they are entitled to their views. What remains more interesting is why parts of the press should so often and loudly repeat this ‘repentant critic’ trope in aid of such a struggling industry.

One more recent example is that of Zion Lights, whose billing in the Daily Mail as “the former XR [Extinction Rebellion] communications head” has been countered by that organisation. Lights’ shift of position – leaving the Extinction Rebellion to campaign in favour of nuclear power – was featured between June and September 2020 in City AM, the Daily Mail (twice) and the Daily Telegraph, as well as in an article on the BBC News website. Then, in a second round of attention in October, the story was again covered by the Mail, with Lights also featuring in The Sun, this time with a spin (since debunked) targeting wind power.

And as if this were not curious enough, the former BBC Radio 4 Today programme anchor John Humphrys, a prominent and respected figure in national media, also picked up the story with a long article in the Daily Mail that span a similar ‘repentant critic’ storyline in his own way.

What is even more notable about this specific instance of a general syndrome is that Lights – the individual at the heart of this story – has (to her credit) made no effort to conceal that she was employed for a period by a high-profile industry-supporting public relations outfit with a long track record of unashamed advocacy of nuclear power – the US Environmental Progress organisation.

A lack of voices for renewables

The implications here go beyond any individual. What is strange is that media attention is so strong on these kinds of arguments, while counter-commentary is so relatively quiet. After all, whilst not infallible, environmental concerns about nuclear power have over the years generally been broadly vindicated. Whichever side one is on, it has to be admitted – despite repeated UK government and industry denials – that formerly hidden costs have been revealed, ambitious construction plans have failed, protracted waste problems remain unresolved, and accidents once claimed to be of negligible likelihood, have in fact occurred.

With regard to ‘repentant critics’, then, the crucial question is this. With renewables displaying such massively improving performance worldwide, where are the high-profile media platforms for their own ‘repentant critics’? Why is it a technology that is so markedly declining that supposedly triggers such newsworthy shifts of view?

Nor are these odd patterns restricted to traditional media. Social media also seems susceptible. At the same time as Lights’ oddly prominent personal journey was garnering so much unquestioning news attention, other striking developments were underway on Twitter. Here, the Friends of Nuclear Energy set up shop in December 2019, the UK Pro Nuclear Power group (UKPNPG) in April 2020, and Mums for Nuclear UK in July 2020.

Official UK nuclear attachments are treated as an unquestionable given

In an especially intriguing example, GreensForuclearEnergy has been active on Twitter since May 2019, spending considerable effort promoting nuclear power and attempting to change the position of the Green Party. Then Liberal Democrats for nuclear power (LDs4nuclear) set up on Twitter in October 2020. In taking up our invitation to respond to core questions raised in this article, GreensForNuclearEnergy pointed to its website, on which it emphatically urges “no compromise to combat climate change”.

This Green Party case is particularly noteworthy, since it is (strangely given underlying patterns of public concern on nuclear issues), the only organised political force in England collectively offering a consistently sceptical position about nuclear power in Parliament. With the longstanding Green grounding on this issue so strong over a half-century, it is especially strange that this development should come at a time when – at least for the Greens – the argument is more over than it has ever been.

What remains particularly striking about all the instances we cite is that none engage substantively with the real-world performance of nuclear power as it is. Despite vivid rhetorics around needs for ‘science-based’ policy – and occasionally colourful fear-mongering about intermittency ‘putting the lights out’ – none of these prolific voices address (let alone refute) the worldwide substantive picture that shows nuclear power overwhelmingly to be slower, less effective and more expensive at tackling climate disruption than are renewable and storage alternatives.

UK government policy

Despite the surface commitment, we see this trend in UK government energy policy too. Dig into more specialist civil service policy papers and you find spiralling prices and little in the way of an energy-related case for nuclear power. But – in a remarkable departure from the normally diligent attention to costs – the most recent energy white paper ignored all that boring economic detail. Official UK nuclear attachments are treated as an unquestionable given.

If a persuasive explanation is sought for this persistent intensity of UK government support for nuclear power, then the real picture seems clear behind the distractions. Official UK defence documentation, many unanswered national and international media reports, brief admissions to Parliament and explicit statements in other nuclear-armed countries all make it pretty clear that the reasons are actually more military than civilian.

So, it might be understood why deep-rooted nuclear interests are seeking to hide these inconvenient facts behind pretty pictures of the West Highlands. But why is the media so keen to help, squirrelling realities away from view behind tales of repentant environmentalists? Why is so much new noise building up behind nuclear power in formerly critical political parties, just when the case has grown weaker than ever?

Profound issues are raised here, not only concerning the cost and speed of climate action, but about the independence and professionalism of the UK media and the health of British democracy as a whole. Whichever opinion we each take on nuclear issues – and whatever the undoubted uncertainties and ambiguities – we should all care very deeply about this.