Hit $100bn target or poor countries face climate disaster, the Gambia tells Cop26

West African nation’s environment minister says richer countries must finally honour funding commitment made at Cop15 in 2009

Rich countries must hit their $100bn climate finance target in the last week of Cop26 or it will be catastrophic for the poorest nations suffering the most from the climate crisis, the Gambian environment minister has warned.

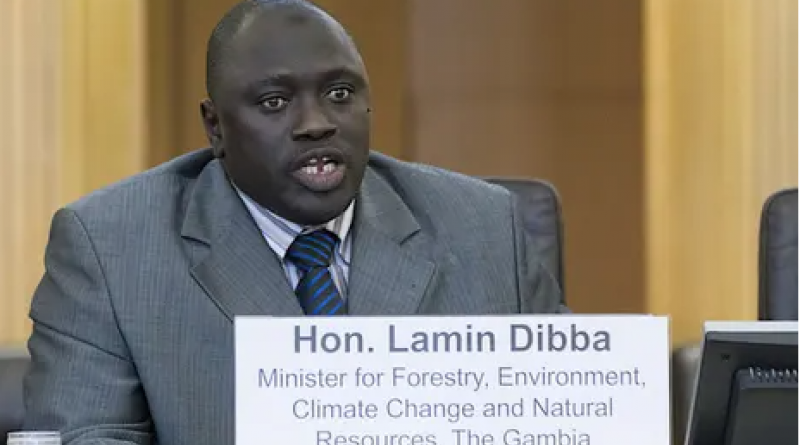

In an interview with the Guardian as he prepared to leave for Glasgow, Lamin B Dibba urged developed countries to finally honour the annual funding commitment that was made 12 years ago at the Copenhagen climate summit (Cop15) – but which has never been achieved.

“We [the world’s least-developed countries] bear the biggest brunt of the impact of climate change and we would like to see the commitment that was taken by the developed countries be fulfilled,” he said.

If the $100bn (£75bn) target was not reached, he added, the consequences for those nations would be grave. “It would be catastrophic because we need those resources,” Dibba said.

The leaders of the wealthiest countries at Cop26 are reported to be scrambling to reach the $100bn figure, with Boris Johnson keen for positive announcements after criticism of the summit’s lack of progress.

Poor countries were given about $80bn (£60bn) in climate finance in 2019, the latest year for which full data is available, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

The Gambia, Africa’s smallest mainland country, has been praised by some for its plans to tackle the climate crisis. A recent analysis found it to be the only “Paris-compatible” country in the world, with plans for keeping to the goal of limiting global heating to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels by 2100.

But Dibba said that without a hefty injection of climate finance and other support it would be difficult for the west African nation to respond properly.

He called on richer countries to increase their ambition, warning that unless they did, Gambian efforts would be in vain. “We have our long-term vision but we would also want to see [it] on the part of the developed nations, because without that all the efforts we are doing will be negated by the impact of their economic activities,” he said.

Coastal and low-lying, the Gambia has been suffering the impact of climate change for years. Its farmers have seen crop yields decrease due to irregular rainfall; its tourist industry is grappling with beach erosion; and many residents, particularly the poorest, face regular flooding and other natural disasters.

Dibba wants to see greater investment in resilience and adaptation programmes to build the capacity of vulnerable communities to withstand extreme climate events, “so that whatever happens they will be able to weather the shock.”

He says developing countries do need to be inward-looking as well as focusing their demands on richer nations, and says the Gambia is building its own national climate fund with initial investment coming from the government.

But without the financial and technical support of the big global powers, countries such as the Gambia, which is responsible for less than 0.01% of annual global emissions, fear they will continue to suffer disproportionately from a crisis they did very little to create.

“It’s important we shift the paradigm from ‘business as usual’ to a more realistic plan for the entire globe,” said Dibba. “Because if they [the richer countries] don’t, what will happen? Yes, we will suffer, and the Gambia is emitting 0.01% of greenhouse gases. But the consequence, the economic damage, the cost to society … you quantify this.”

Additional reporting by Omar Wally

8 November 2021

The Guardian