Meltwater runoff from Greenland becoming more erratic.

As world leaders and decision-makers join forces at COP26 to accelerate action towards the goals of the Paris Agreement, new research, again, highlights the value of satellite data in understanding and monitoring climate change. This particular new research, which is based on measurements from ESA’s CryoSat mission, shows that extreme ice melting events in Greenland have become more frequent and more intense over the past 40 years, raising sea levels and the risk of flooding worldwide.

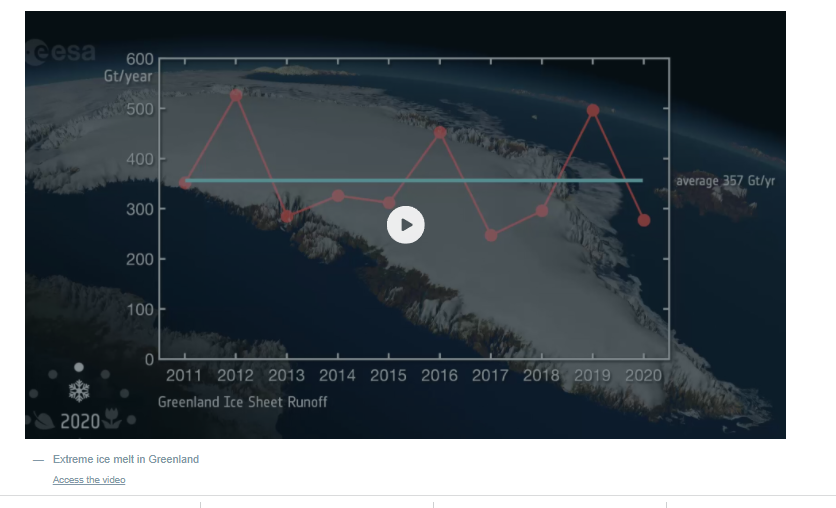

The findings, published this week in Nature Communications, reveal that Greenland’s meltwater runoff has risen by 21% over the past four decades, and has become 60% more erratic from one summer to the next.

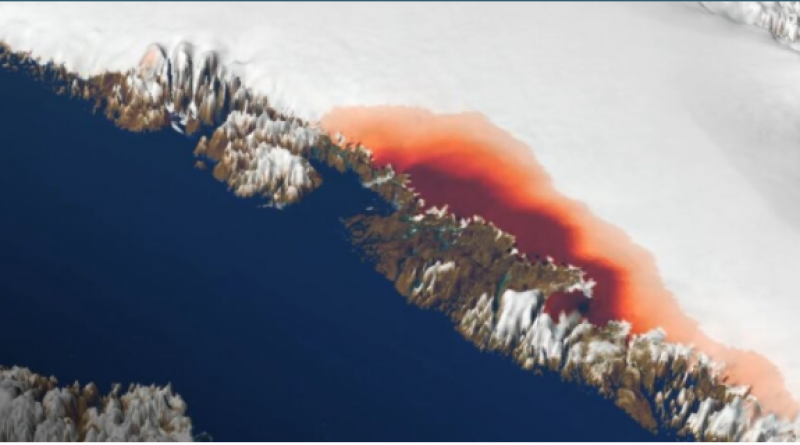

Over the past decade alone, 3.5 trillion tonnes of ice have melted from the Greenland ice sheet and spilled into the ocean. This is enough to cover the entire UK with meltwater 15 metres deep or cover the entire city of New York with meltwater 4500 metres deep.

The research was funded by ESA as part of its Polar+ Surface Mass Balance Feasibility project and used measurements from the Agency’s ice mission CryoSat – and it is the first study to use satellite data to detect ice-sheet runoff from space.

Lead author, Dr Thomas Slater, a research fellow in the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling at the University of Leeds in the UK said, “As we’ve seen with other parts of the world, Greenland is also vulnerable to an increase in extreme weather events.

“As our climate warms, it’s reasonable to expect that the instances of extreme melting in Greenland will happen more often – observations such as these are an important step in helping us to improve climate models and better predict what will happen this century.”

The research shows that between 2011 and 2020 meltwater runoff from Greenland raised the global sea level by one centimetre. Worryingly, one third of this total was produced in just two separate years, in 2012 and 2019 – two hot summers when extreme weather led to record-breaking levels of ice melting not seen in the past 40 years.

Raised sea levels caused by ice melt heightens the risk of flooding for coastal communities worldwide and disrupts Arctic Ocean marine ecosystems on which indigenous communities rely for food. It can also alter patterns of ocean and atmospheric circulation, which affect weather conditions around the planet.

During the past decade, runoff from Greenland has averaged 357 billion tonnes per year, reaching a maximum of 527 billion tonnes of ice melt in 2012, when changes in atmospheric patterns caused unusually warm air to sit over much the ice sheet. This was more than twice the minimum runoff of 247 billion tonnes that occurred in 2017.

The changes are related to extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, which have become more frequent and are now a major cause of ice loss from Greenland because of the runoff they produce.

Dr Slater said, “There are, however, reasons to be optimistic. We know that setting and meeting meaningful targets to cut emissions could reduce ice losses from Greenland by a factor of three, and there is still time to achieve this.”

These first observations of Greenland runoff from space can also be used to verify how climate models simulate ice sheet melting which, in turn, will allow improved predictions of how much Greenland will raise the global sea level in the future as extreme weather events become more common.

Study co-author, Dr Amber Leeson, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Data Science at Lancaster University in the UK, said, “Model estimates suggest that the Greenland ice sheet will contribute between about three and 23 cm to global sea-level rise by 2100.

“This prediction has a wide range, in part because of uncertainties associated with simulating complex ice-melt processes, including those associated with extreme weather. These new spaceborne estimates of runoff will help us to understand these complex ice-melt processes better, improve our ability to model them, and thus enable us to refine our estimates of future sea-level rise.”

Finally, the study shows that polar-orbiting satellite altimeters are able to provide instant estimates of summer ice melting, which supports efforts to expand Greenland’s hydropower capacity, and Europe’s ambition to launch the Copernicus Sentinel Expansion CRISTAL mission to eventually succeed CryoSat.

ESA’s CryoSat mission manager, Dr Tommaso Parrinello, said, “Since it was launched over 11 years ago, CryoSat has yielded a wealth of information about our rapidly changing polar regions.

“This remarkable satellite remains key to scientific research and the indisputable facts, such as these findings on meltwater runoff, that are so critical to decision-making on the health of our planet.

“Looking further to the future, the Copernicus Sentinel Expansion mission CRISTAL will ensure that Earth’s vulnerable ice will be monitored in the coming decades. In the meantime, it is imperative that CryoSat remains in orbit for as long as possible to reduce the gap before these new Copernicus missions are operational.”

3 November 2021

esa