‘The world is burning’: how Australia’s longest-serving fire chief became a climate champion

Greg Mullins says after the ‘black summer’ bushfires it is time for politicians to act on global heating.

The year 2019 was Australia’s hottest and driest on record. By 2040, those conditions – temperatures 1.5C above normal, contributing to the worst bushfire season the east coast has ever seen – will be average. By 2060, on current projections, it would be considered “exceptionally cool”.

The 2019-20 fire season, dubbed “black summer”, will become the norm.

It’s a grim future that has turned Greg Mullins, the longest-serving fire commissioner in Australia, into a climate campaigner.

“It’s gonna be a very, very dangerous place to live – not Australia, planet Earth,” Mullins says. “I’m deeply worried about my grandsons and what they’re inheriting from us.”

That worry is at the heart of a new book, Firestorm, written after that terrible summer of bushfires and the resulting royal commission. The book is dedicated to Mullins’ grandsons, Eamon and Oli, and their future safety.

“I want you to know that I tried my best,” it says.

In 2019, Mullins formed a coalition with other former fire chiefs to call for a policy response to the climate emergency. In February 2020, with much of Australia still burning, they were hopeful that the federal government would finally be pushed to act on the climate emergency.

But then the pandemic hit, and the problem of Australia’s non-existent climate policy was pushed to the back burner once more.

“That’s incredibly convenient for a government that just seems to find it extremely difficult to move with the public sentiment on climate, because it’s pretty overwhelming,” he says.

In his new book, Mullins argues that it is time for politicians in Australia to put the fate of the country ahead of political struggles.

“I’ve worked in government for many years and a rare commodity in government, I think, is courage,” Mullins says. “They expect it of public servants, police commissioners, fire commissioners, generals in the army, and health department heads, but it’s pretty rare, I think, to see politicians step up and say: well, this is a crisis.”

‘These things are unprecedented’

Mullins retired as commissioner in 2017, after 39 years as a professional firefighter, and spent the 2019-20 fire season on the back of a fire truck as a volunteer for the New South Wales Rural Fire Service.

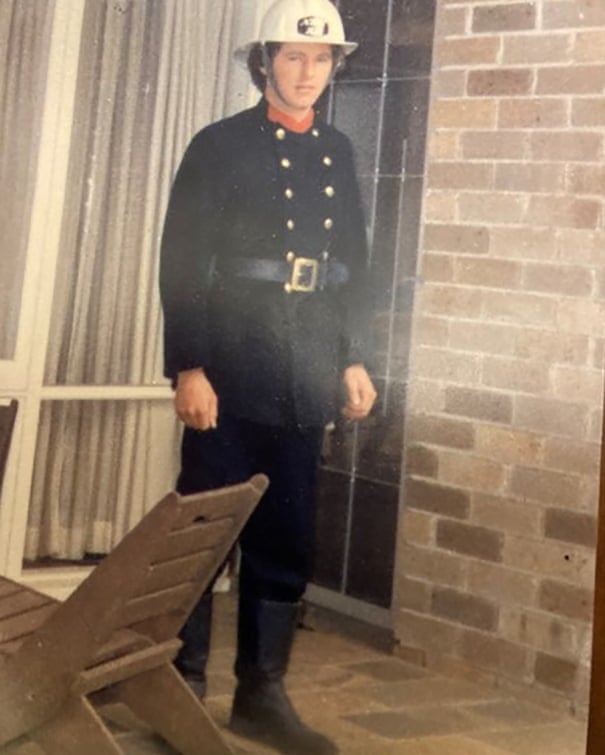

He joined the RFS as a volunteer at age 13, tagging along after his father, Jack, and experienced his first burn over – long, terrifying minutes lying face-down in a wheel-rut while the flames ran over him, leaving him “looking like a boiled lobster” – the day before his year 12 maths exam.

It’s fair to say he has more experience waging and coordinating bushfire campaigns than anyone else in the country. But the 2019-20 fire season was the worst he had ever experienced.

“I’ve very rarely felt that my life was in danger the way I did that summer, on multiple occasions,” he says.

In December that year, at Blackheath in the Blue Mountains, Mullins and another firefighter were engulfed in flames in a gully after getting caught behind a house, in the middle of the night. In contravention of years of accepted fire behaviour, the fire conditions had not dampened overnight – the humidity had not changed, the temperature had not dropped.

“It should not have been burning like that at night,” Mullins says. “People’s eyes glaze over when I talk to them about it, because most people don’t realise you have to be an amateur meteorologist to be a firefighter. But all these things are unprecedented. In the old days we’d really up the attack on a bushfire at night, because that’s when it died down, but they don’t necessarily do that any more because the atmosphere is warmer and all the dynamics have changed.”

On the NSW south coast one week later, Mullins saw walls of flames kilometres long and more than 60 metres high, twice the height of cool-climate rainforests that also should not burn, but which had slowly dried out over decades.

“I saw kangaroos dying on the side of the road that had been burned to death – I’ve never seen that before, because they know where to go and how to get away, but there was no escape,” Mullins says.

“I heard thunder, saw lightning up in the sky – no rain – but then incredible winds … when you get a pyro-convective storm, the winds can come from every direction. It just changes.”

Pyro-convective storms, or firestorms, used to be rare events. Just 60 were recorded between 1978 and 2018. In the summer of 2019-20, meteorologists recorded 35 in just six months.

It was a pyro-convective storm that picked up a firetruck on NSW-Victorian border on 30 December 2019, flipping it on to its back and killing 28-year-old volunteer firefighter Samuel McPaul.

On the worst fire days, Mullins says, it is not safe to send firefighters out. People who stay behind to protect their homes in those conditions will either be on their own, or put in jeopardy the lives of firefighters who go to save them.

“It was one of the reasons I decided I wanted to retire as commissioner, because one death of a firefighter is one too many,” he says. “I got to the stage where I couldn’t really deal with that any more. I didn’t want to tell another family that they’d lost a loved one.”

On 31 December 2019, two Rural Fire Service trucks fighting a bushfire on the NSW south coast, south of Nowra, caught on fire, forcing the crew to walk out.

“When I saw that, my immediate thought was: that fire truck they were in was bought on my watch when I was commissioner, and it wasn’t designed to withstand that sort of heat,” Mullins says. “That feeling of responsibility ... oh, thank God they got out.”

For the most fire-prone areas of the country – Gippsland and the Victorian alps, the NSW south coast, southern highlands and the Blue Mountains – the only option left for emergency services is to order a mass evacuation, as both Victoria and NSW did over black summer.

But even that has its risks, if you don’t do it early enough. Driving past the kilometres-long stretches of cars filled with people evacuating the NSW south coast on New Year’s Eve in 2019, Mullins says, he had “visions of fires, sweeping through the highway and just burning all those people in the cars”.

“Somehow the police got them out, I don’t know how.”

The change in bushfire behaviour over the past 40 years is so significant that Mullins compares it to the atom bomb.

“It’s like they (bushfires) have suddenly gone nuclear and we’ve only got conventional weapons,” he says. “Nature has overwhelmed us.”

Australia’s ‘embarrassing’ climate position

The royal commission into national natural disaster arrangements warned that the techniques used to control major bushfires would not work under the kinds of catastrophic fires the country would face under global heating.

The inquiry was explicitly told not to examine climate change but found the worsening fires and the worsening climate to be inextricably linked. It made 80 recommendations – some of which have been accepted by the federal government, but a number of which – including the recommendation for a sovereign national aerial firefighting fleet, and the recommendation for national climate principles – have only been noted or accepted in principle.

Currently, Australia’s aerial firefighting arrangements are contingent on there being minimal overlap between the fire seasons of northern and southern Australia, and no overlap between fire seasons in the northern and southern hemisphere. That is no longer the reality.

“The whole world is burning at the same time,” Mullins says. “We need to take action on emissions, and Australia’s not living up to its international responsibilities. I find it really embarrassing. I’ve been speaking to some friends from the US this morning, former fire chiefs from California, and it’s a bit embarrassing when they talk about what Joe Biden’s doing with climate and Scott Morrison’s doing, it’s a very big contrast.”

Morrison has been in the US, meeting with Biden and other world leaders. On Friday the federal treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, gave a speech arguing that setting a target of net zero by 2050 was necessary for economic security. Morrison swiftly shut it down, telling reporters in Washington that Australia had made no such commitments.

Instead of looking at emissions reduction, Australia’s post-fire debrief is stubbornly focused on hazard reduction burning, land clearing and environmental red tape: interventions that, research and first-hand experience has shown, are not effective against bushfires in extreme or catastrophic conditions.

“It’s just grabbing on to simplistic single solutions, and none of that’s going to work,” he says. “The problem is too big to solve, and people don’t like being in a position where they feel they can’t control things so they’ll grasp at simplistic suggestions, and they’ll grasp at blame.”

The solution Mullins puts forward is political: vote for politicians who have shown a willingness to take action on emissions reduction, not just pay it lip service.

“It’s a political problem at the moment,” says Mullins. “You’ve got a government with a very slim majority in coalition, and one of the coalition partners just can’t get there – despite its former base, farmers, saying we’re on board with this.”

26 September 2021

The Guardian