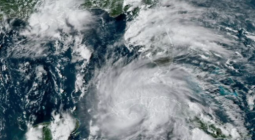

How the climate crisis played a role in fueling Hurricane Ida

Hurricane Ida made landfall near New Orleans on the 16th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina.

Hurricane Ida made landfall last weekend near New Orleans as a Category-4 storm, lashing the region with winds of up to 150mph (240kph), heavy rains and several feet of storm surge on the 16th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina.

Mercifully, levees held around the Big Easy after being reinforced in the wake of the 2005 storm which decimated neighborhoods and left 1,800 people dead. However the storm still caused massive flooding outside of New Orleans in communities like Houma and LaPlace.

Four deaths were reported in Louisiana and Mississippi, including two people killed when a highway collapsed in torrential rain.

And 43 people were killed in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and Pennsylvania amid unprecedented flooding across the northeast as the remains of Ida lashed the region on Wednesday night.

Officials say that the death toll was at least 26 people on in New York City and New Jersey including a two-year-old boy.

New York Police Department reported that at least eight people were killed when their basement apartments flooded, and in Elizabeth, New Jersey, five people were found dead after an apartment complex flooded.

Ida is the joint-fifth strongest hurricane ever to make landfall amid what’s shaping up to be a highly active Atlantic season. Last year saw a record-breaking 30 named storms which wreaked waves of damage in the US, Central America and the Caribbean.

While Ida had now weakened to a tropical depression, there remains significant threat of flash flooding as it marches north. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Weather Prediction Center is warning of torrential rainfall which could lead to once-in-a-century events in some areas.

Several factors linked to the climate crisis are helping to fuel more powerful, destructive storms like Ida, scientists say.

The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s leading authority on climate science, found that storms with sustained higher wind speeds – in the Category 3-5 range – have likely increased in the past 40 years.

The ocean absorbs over 90 per cent of excess heat caused by greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of fossil fuels and that warm water feeds hurricanes.

“There is more energy available, so intensification of these hurricanes is expected,” Dr Susan Lozier, president of the American Geophysical Union and an expert on the interaction of oceans, hurricanes and climate change, told The Independent. “And intensification brings more winds.”

More than a million people lost power when Ida toppled thousands of transmission lines and knocked 216 substations offline. Utility companies warned that thousands could remain in the dark and without air conditioning or running water for several weeks amid stifling heat and humidity.

(AP)

In New Orleans, temperatures were expected to feel like 106 degrees Fahrenheit (41C) on Wednesday.

As the planet warms, more moisture is held in the atmosphere, which means that storms also bring the possibility of a lot more rainfall.

“Within about 150km of the storm center, we expect average rain flux rate to increase about 7 per cent for every one degree Celsius of global warming,” Dr Tom Knutson, senior scientist with the NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, told The Independent.

In addition, global sea level rise is compounding the danger of storm surge.

“Storm surge will produce a greater inundation as background sea level is higher systematically over almost all regions of the globe because of global warming,” Dr Knutson said.

The Gulf region has among the fastest rising sea levels in the US and in Louisiana, sea level is now 24 inches higher than in 1950.

“As with everywhere else, the Gulf of Mexico has seen sea level rise because the oceans are warmer, but it's also due to the fact that there's been groundwater extraction and the ground has subsided over many years, making this much worse,” Dr Lozier said.

Climate change does not necessarily mean there will be more storms, Dr Knutson explained, and in fact the number may even decrease. However since about 1980, there is evidence that global warming has increased the chance of hurricanes ramping up into more extreme events.

There have been observations that hurricanes are now also moving more slowly, but Dr Lozier cautioned that the science is not as settled as with the other climate-driven factors impacting storms. “But slow-moving hurricanes really are bad news,” she added.

Research published last year in the journal Nature Climate Change proposed that changes in the rapidly warming Arctic region are contributing to weakened atmospheric circulation, which in turn may impact hurricane speed.

When combined with higher levels of rainfall, storms which squat over regions for extended periods can lead to catastrophic flooding as was the case with 2017’s Hurricane Harvey in Houston, Texas.

3 September 2021

INDEPENDENT