EU Eyes First-of-a-Kind Border Levy in Climate Fight

The European Union is planning to slap an import levy on steel, cement and aluminum produced in countries with lower environmental standards, as it seeks to become a world leader on climate without harming domestic producers.

In a move no other country in the world has taken, the European Commission wants to introduce a system imposing a penalty for bringing into the bloc emissions embedded in goods, according to a person familiar with the proposals due to be unveiled next month. The levy will be based on carbon costs domestic producers already face, and will also affect fertilizers and electricity.

Importers will have to buy special certificates at a price linked to the EU Emissions Trading System, the person said, asking not to be named commenting on private discussions. Carbon prices in that market have soared to records this year.

The planned measure is part of a broader package to be put forward on July 14, in a bid to align the EU economy with stricter emissions-reduction targets for 2030. The 27-nation bloc is tightening its environmental rules in an overhaul that will affect all areas from transport to energy production and trade. The overarching goal of the Green Deal is for Europe to become the world’s first climate-neutral continent by the middle of the century.

EU leaders have repeatedly said in summit communiques that they would welcome a border-levy mechanism. Still, hashing out the details of the so-called Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism may stir long debates within the bloc. The issue isn’t on the agenda of the Group of Seven meeting this month, though one official said it could be discussed informally.

Dual Goal

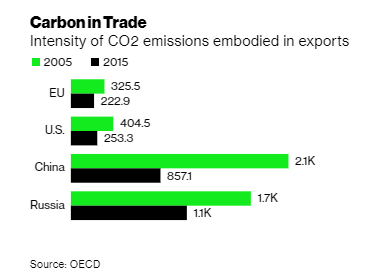

The EU wants to hit two birds with one stone: provide a level playing field for its businesses and encourage more climate action from countries outside the bloc. But its plans are already causing diplomatic unease in countries from Ukraine to China and India. The planned levy will be proposed just five months before a crucial climate summit hosted by the U.K., where coalition-building will be key to ensuring major emitters step up their efforts.

If the proposal escalates trade tensions, the CBAM may wind up being a tool the EU wields rather than a full-blown penalty for imported pollution that eventually gets extended to cover more sectors. The EU has already learned a trade and climate lesson when it included flights to and from Europe in its carbon market last decade, putting a price on every ton of CO2 discharged by planes. Following an uproar and threats of retaliation from Brazil to the U.S., Russia and China, the EU backtracked, scaling down its program.

In the most optimistic scenario painted by some analysts and EU diplomats, Europe’s plans would lead to the creation of a “climate club” across continents. That would need endorsement from the U.S. administration, which hasn’t decided yet what regulatory approach to follow to reduce greenhouse gases.

The commission is considering a transition period of up to three years before full entry into force of the mechanism in January 2026, according to a draft proposal. Between 2023 and 2026 it could use a simplified system “with the objective of reducing the risk of disruptive impacts on trade flows and alleviating the initial administrative burden,” the proposal said. Revenues would go into the EU budget.

The energy industry has also called for the introduction of CBAM but many companies want the tool to be an addition than alternative to free allowances that they now get as a shield against carbon leakage. That’s another sticking point that policy makers will need to tackle.

Given all the sensitivities, the draft regulation may still change even before it’s adopted by the commission in July. Once it’s been put forward, it will have to be approved by the European Parliament and by member states to become law. That process involves negotiations that can take as long as two years.

Under the draft, importers in the affected sectors will be required to buy electronic emission certificates at prices corresponding to those in the EU ETS, the world’s biggest cap-and-trade program for greenhouse gases. Each CBAM certificate will correspond to one metric ton of emissions embedded in the imported goods.

Market Pricing

The cost of emissions in the EU carbon market has soared 10-fold in the past four years as the bloc bolstered the program and vowed to step up climate action. Benchmark permits to pollute jumped to an all-time high of 56.90 euros on May 14 and ended the day at 51.40 euros on Wednesday.

The price of CBAM certificates will be calculated as the average of the closing prices of all government auctions of carbon permits during each calendar week, according to the draft.

“In case the actual emissions cannot be adequately verified, including cases where the authorised declarant has failed to submit the necessary information, the number of CBAM certificates to be surrendered shall be determined in accordance with default values,” the commission said in the draft, which may still change before publication.

If the embedded emissions originate in a country which has carbon pricing, the importer would be entitled to claim a reduction in the number of CBAM certificates to be surrendered. Such an application would have to be in line with a special carbon price certification system that the commission will design separately.

Importers will face a penalty for failure to comply with the regulation, according to the draft. They will have to pay three times the average price of CBAM certificates in the previous year for each certificate that wasn’t surrendered.

(Updates with details of legislative process from the seventh paragraph)

2 June 2021

Bloomberg Green