Net-zero emissions targets are vague: three ways to fix.

To limit warming, action plans from countries and companies must be fair, rigorous and transparent.

Five years ago, the United Nations Paris climate agreement set a ceiling for global warming at well below 2 °C, ideally 1.5 °C relative to pre-industrial levels. World leaders also agreed to balance greenhouse-gas emissions in the second half of the century, so that the sum of all greenhouse gases emitted from human activities is zero. In response, ever more countries, institutions and companies are announcing net-zero targets1,2. Recent examples include the United States, China, the European Union, the technology firm Microsoft and an alliance of European airports. These welcome signs of intent come with difficulties.

Plans are hard to compare, and definitions loose. The details behind ‘net-zero’ labels differ enormously. Some targets focus solely on carbon dioxide. Others cover all greenhouse gases. Companies might consider only emissions under their direct control, or include those from their supply chains and from the use or disposal of their products. Sometimes the targets do not aim to reduce emissions, but compensate for them with offsets.

Important questions are being overlooked. Should some sectors, such as electricity generation, reach net zero earlier to counterbalance harder-to-abate sectors including heavy industry? Is it fair to expect emerging economies to reach net zero on the same schedule as long-industrialized ones? Without careful attention to such issues, individual achievements risk being too weak to deliver the collective climate goal of the Paris agreement.

Critics could argue that vague targets are better than none. But the stakes are too high to take comfort in mere announcements. Everyone need not make the same choices. But without more clarity, strategies behind net-zero targets cannot be understood; nor can their impact be evaluated.

Here we call on nations, companies and the researchers advising them to clarify three aspects of their targets: their scope; how they are deemed adequate and fair; and concrete road maps towards and beyond net zero. A key date for this clarity will be the next UN climate summit, in Glasgow, UK, in November, where countries will present new climate pledges.

Scope

Targets must specify which emission sources and which gases are covered (CO2, all greenhouse gases, or a subset); when net zero will be reached, and whether the intent is to reduce, remove or offset the emissions.

The choice of gases being tackled affects the outcome for the climate. CO2 is the main cause of rising global temperatures; it accumulates and lasts for hundreds to thousands of years in the atmosphere. Bringing CO2 emissions down to net zero halts further warming, but the impact of CO2 already present in the atmosphere will linger for centuries. By contrast, shorter-lived greenhouse gases, such as methane, last for years to decades. Reducing these would diminish their contribution to warming relatively quickly. But eliminating their emissions is impossible at present, and there are currently no technologies to actively remove them from the atmosphere, unlike CO2.

Each country or organization takes a different tack. The EU targets all greenhouse gases by 2050. China’s net-zero plan focuses on balancing only CO2 emissions, by 2060. The current presidential administration’s climate plan for the United States aims to reach net zero by 2050, but has yet to specify which gases are covered. The Paris agreement considers all greenhouse gases; emissions that cannot be eliminated have to be balanced by removing an equivalent amount of CO2 from the atmosphere. The UN has agreed a metric to determine this equivalent amount: the greenhouse gas Global Warming Potential over 100 years, or GWP-100.

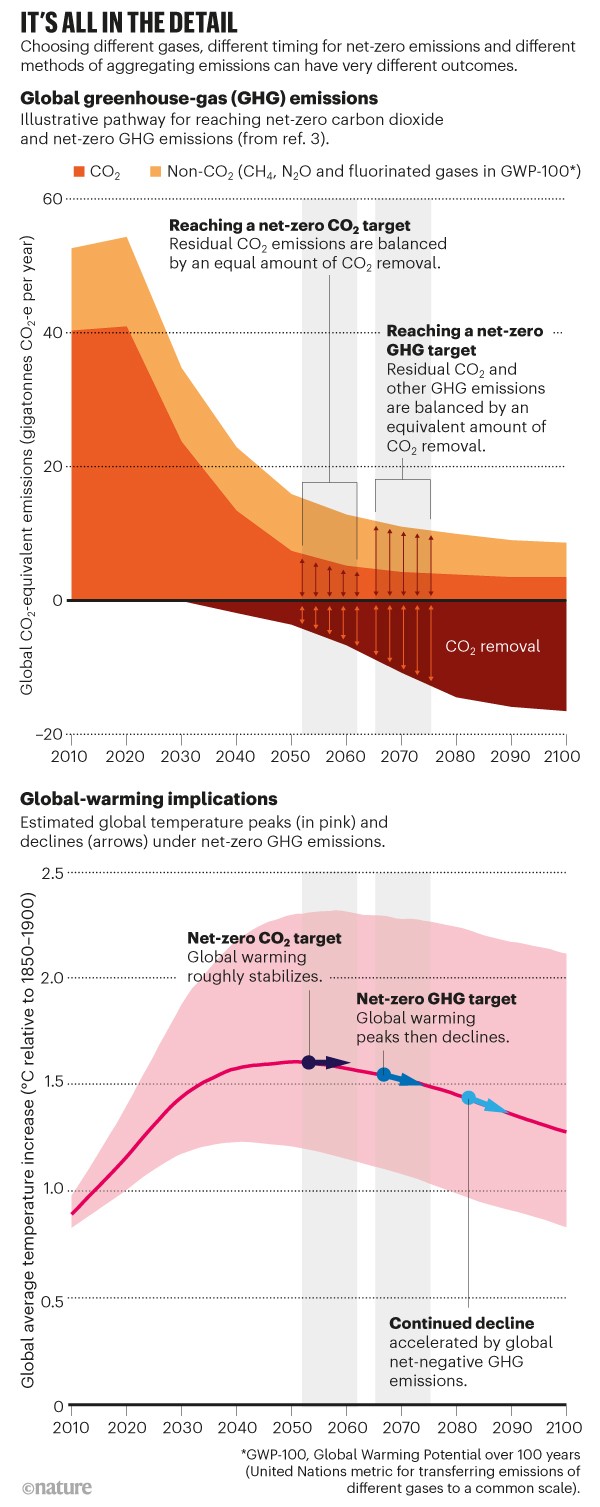

All available Paris-compatible pathways to meet net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions use a combination of three strategies. These are: rapid and large reductions in CO2; additional deep reductions in non-CO2 greenhouse gases; and a ramping up of strategies to remove CO2 from the air. (One specific pathway is shown in ‘It’s all in the detail’). In the pathways for limiting warming to 1.5 °C presented by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) net-zero CO2 emissions are reached around 2050 (2046–55). However, net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions would only be reached one or two decades later (2061–84)3.

Because CO2 removal is used to balance other, shorter-lived greenhouse gases, the Paris agreement’s net-zero target will achieve more than stabilizing global warming: temperatures will peak and slowly decline4,5 (see ‘It’s all in the detail’). But the balance is delicate: change the metric or the gases covered, the speed at which various gases are reduced or the proportion of reduction versus removal, and the peak and rate of temperature decline could be very different5. Temperature might not even decline at all.

Vague terms abound. For example, ‘carbon neutral’ and ‘climate neutral’ are sometimes synonyms for net-zero CO2 and net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions, sometimes not. France’s strategy, for instance, speaks of carbon neutrality but spans all greenhouse gases. Consistency, clarity and accuracy are essential.

The scope of the sources of emissions covered also varies. Company targets might cover only emissions resulting from their direct activities, or they might also include emissions across their value chains. For example, Swedish furniture giant IKEA has a net-zero target that includes all emissions from its entire supply chain. So does Microsoft, which by 2050 also plans to neutralize all CO2 it has emitted since its founding in 1975. By contrast, ACI Europe, representing more than 500 European airports, has set a net-zero CO2 target for 2050 that covers just buildings and operations on land, not emissions from aeroplanes. Only 2% of emissions of all aviation activities that pass through these airports is addressed.

The anticipated role of CO2 removals also needs more clarity. Target setters should declare how they will combine emissions reductions, direct removals and offsets. Direct CO2 removals are those under the control of the organization or entity. Offsets are purchased reductions or removals fulfilled by someone else, elsewhere. On the whole, direct emissions reductions are preferable. Strategies for removal or offsetting often have uncertain effectiveness and could come with more risks.

For example, some solutions require a lot of land. This can have knock-on impacts on biodiversity, and the security of food and water supplies. Planting a forest, for example, might displace agriculture; planting monoculture energy crops could reduce species diversity. The permanence of such biological removals remains uncertain. The long-term carbon-storage capacity of forests and soils is not well known, and there can be no guarantee that a forest won’t later be logged, devastated by a forest fire or altered by climate change6.

Engineered solutions — such as using chemical filters to suck CO2 from the air to be buried underground — are still nascent. Deploying such technologies on a scale large enough to have a global impact remains speculative. Ultimately, costs and social acceptance might limit any CO2 removal option. For example, communities might oppose landscapes being transformed or CO2 being stored beneath their homes6. Net-zero declarations should say how these risks will be managed.

Adequacy and fairness

Countries and companies that set net-zero targets generally assume, and sometimes claim, that these will meet the global goals of the Paris agreement. However, this involves implicit assumptions about what a fair contribution would be and what others should contribute. Ethical judgments are unavoidable, even if unvoiced.

What is considered ‘fair’ differs across countries and communities. All of these are in different stages of development, with a variety of opportunities, financing and resources available, and differing contributions to global warming. For example, Singapore is a small, densely populated country with limited potential to deploy renewables, but is rich and has high capacity to finance action. The EU has been contributing to global warming for more than a century and was heavily deforested in the past, which means it now has significant potential for reforestation. Yemen has some of the best solar-energy resources in the world, but, as a least-developed country experiencing continuing unrest, it has little access to the necessary investments. Similar diversity applies to economic sectors. The agriculture and forestry sector has clear opportunities for CO2 removal; aviation and metals industries don’t.

Net-zero targets defined using metrics other than GWP-100 also shift the mitigation burden between gases, and thus between sectors and countries5,7–9. Giving less weight to methane would make it easier for countries with high emissions from agriculture to claim that net zero has been reached. However, this would also result in more global warming unless other countries — with mainly CO2 emissions — agree to reach net zero sooner.

Climate policies can be win–win, but emissions targets are a zero-sum game. If one country or company does less, others have to do more to achieve the same global temperature outcome. If a country takes 2065 as its national net-zero CO2 target for limiting global warming to 1.5 °C, for example, it implicitly expects that all other countries together will reach net-zero CO2 before the global average of around 2050.

Parties to the Paris agreement should proactively disclose why they consider their net-zero targets to be fair and adequate. This is currently requested for near-term national mitigation targets (the nationally determined contributions, or NDCs) but not yet for longer-term targets such as net zero.

Fairness issues also arise from carbon offsets. Cheap offsets can mean that a company makes limited effort to address its own emissions. Offsetting emissions through projects in another country outsources any social and environmental risks. Finally, avoiding double-counting of offsets is a challenge — for example, if a reforestation project in Sierra Leone sells an offset credit to Microsoft, this emissions reduction is double-counted if it is also included towards Sierra Leone’s emission target. The climate, obviously, sees the benefit only once. Finally, trade in manufactured goods and energy further complicates the picture of who is responsible for what.

On the whole, cutting emissions locally is preferable to offsetting them. Continued reliance on offsets might become increasingly unrealistic and ultimately unfair to countries that provide the offsets but cannot count those actions towards their own targets.

Two key questions for adequacy and fairness are: would the world still hit net zero if everyone applied this logic? And would it be fair to apply the same logic to all countries?

Self-interests cannot be avoided. Countries often choose fairness principles that favour their situation, overestimating how much their actions contribute to the global goal. Modelling has shown, for example, that if all countries were to pursue the targets they deem fair and in line with 1.5 °C, warming would hit 2 °C10. This is why rigour and transparency are needed to support conversations about what is and isn’t equitable in light of a collective, global target.

Long-term road map

Net-zero targets are more credible if they include milestones, an implementation plan, and a statement about longer-term intent for either maintaining net zero or going net negative. Leaving these out risks inaction, diversions and failure.

For example, the United Kingdom announced in 2019 that it would reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050, but its near-term policies were still off track. In 2020, it published its first NDC for 2030, together with other policy milestones. In combination, these now present a more coherent domestic plan.

Net-zero targets are not end points. They are themselves milestones to meeting net-negative emissions targets further down the road11. Few targets explicitly consider this, but it determines how net zero is best approached.

Those most able to reach a net-negative future need to plan for it now — not out of generosity, but out of necessity, to reach net zero globally. Finland and Sweden, for example, have targets for reaching net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2035 and 2045, respectively, and going net negative thereafter. In the context of an EU-wide net-zero target for 2050, these intentions can compensate for the weaker reductions of other nations with greater technical or political obstacles.

Furthermore, targets must be amenable to tightening. As we experience an increasingly warmer world, nations and companies might decide that action should be taken more rapidly12. Acceleration can be encouraged by setting a regular schedule for revising targets, such as those already in place for the shorter-term NDCs.

Critics might question the value of discussing a road map to net-negative emissions when the world is not even on track to achieve net zero. In our view, these conversations are crucial in shaping a sustainable long-term future for our shared planet.

Next steps

Countries and companies must add rigour and clarity to their net-zero targets, to enable these to be evaluated and assessed (see ‘Checklist’ and Supplementary information).

Research can support improvements in all three aspects. For example, in respect to scope, nature-based carbon sinks are used for direct removals or offsetting. Studies should better characterize risks surrounding the future reliability of such sinks, their potential reversal under climate change and their wider social and ecological consequences.

The area of adequacy and fairness is ripe for work across multiple disciplines. Setting net-zero targets at a country or company level cannot be done only by natural scientists or economists. Ethicists and social scientists are needed to help explore how fairness concepts apply to today’s multinational corporations — which span multiple countries and sectors, and involve staff on incomes ranging from the lowest to the highest. Equity must be made a central part of the process, including in tools used to design net-zero targets so that the wider implications of assumptions and decisions become clear.

For work towards a concrete road map, the UN review process for detailing near-term NDCs — assessing and revising them every five years — is a good starting point. That can be extended to include longer-term net-zero targets. Companies should do the same and apply a standardized review process, considering the aspects we have outlined here.

Today’s targets are only the start of a long journey towards a safer world.

Nature 591, 365-368 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-00662-3

16 March 2021

nature