How to create a net-zero, nature-positive recovery.

- The COVID-19 pandemic saw wild animals roaming empty streets and a drop in emissions in many places around the world.

- Yet these improvements to nature are unlikely to remain, and the environmental crisis is set to worsen in the year ahead.

- Here's how to create a net-zero, nature-positive recovery.

During 2020, many of us saw images of deserted urban areas being reclaimed by animals and heard reports of carbon dioxide emissions plummeting as transportation ground to a halt. A new analysis shows that the US had reached its lowest level of emissions in three decades.

It would be easy to assume that COVID-19 allowed nature to thrive. However, we must not prematurely celebrate nature’s comeback.

Far from downplaying glimmers of hope and beauty that were welcomed interruptions to an otherwise difficult year, acknowledging that these have little impact in the long run will serve us better to achieve meaningful progress.

The outlook on the coming decade may be bleak if we do not seize the narrowing window of opportunity that we have to make systemic changes. By doing this, we can both prevent similar crises in the future and create sustainable, healthy and equitable jobs, societies and economies. The pandemic made an unquestionably strong case for a shift towards a net-zero, nature-positive global economy and, thankfully, we have the knowledge and the tools to make it happen.

Nature bouncing back?

Amidst the tragedies of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economy entering a global recession, you could be forgiven for thinking that it wasn’t all bad news.

We were inundated with delightful images of previously unseen animals strolling through city streets. Mountain goats explored Welsh towns, deer were spotted congregating outside metro stations in Japan and pumas took to the streets of Santiago, Chile.

Wild boars cross a road in a residential area during a COVID-10 lockdown in Haifa, northern Israel, on 16 April 2020. Picture taken April 16, 2020.

Many ecosystems also appeared to have been given time to regenerate, being temporarily spared humanity’s polluted hand. The canals of Venice famously turned clear and plants started to make a comeback in built-up areas such as parks and city squares.

Similarly, due to the slowdown of economic and social activities, air quality improved in many places around the world, including megacities including Delhi, London, New York and various cities in China. Global CO2 emissions and total nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions decreased by as much as 30% and, as car traffic plummeted and industrial production slowed down, the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions followed. It seemed that at least the atmosphere was benefiting from the global pandemic.

Image: World Economic Forum

Lockdowns also highlighted both a fundamental human need for nature and the divisions between those who had access to it and those who did not. For those with a balcony, view of nature or a garden, the lockdowns may not have felt as oppressive. People craved their own patch of green and marvelled at the sight of animals roaming around freely. Nature, we may have thought, was healing.

Sadly, however, the breather that nature appeared to get is not only temporary but is extremely localised. Other areas have not been having the same luck.

Nature loss and climate change on the rise

If not for COVID-19, the year 2020 would have been remembered for environmental disasters that continued despite scattered improvements. COVID-19 news domination was punctuated by reports of wildfires, flooding, tropical storms and the highest temperature ever recorded on Earth.

As pollution levels decreased in many cities, the effects were countered by increased emissions from home activities. Although nitrogen dioxide declined sharply in Italy, China and New Zealand, COVID-19 responses triggered the increase of global ozone concentrations, which contributes to climate change.

Image: REUTERS/Adrees Latif

Lockdowns in countries with high levels of biodiversity also restricted the ability of governments and communities to protect wildlife. Incidences of illegal poaching and deforestation increased in South America, Asia and Africa. Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon increased by 30% in March 2020 compared to the previous year and forest fires lit by land grabbers broke records in Colombia. Illegal fishing is also on the rise in many areas, with fishermen taking advantage of a drop in enforcement capacity.

COVID-19 has also halted the nature-based tourism industry. In many countries, communities relied on this as a source of income, in addition to these funds being used to protect nature. For countries like the Seychelles and Vanuatu, tourism accounts for 30% and 45% of their GDP, respectively. The economic crisis may prevent such tourism from returning for quite some time, while conservation is unlikely to be perceived as a priority for government spending.

The improvements witnessed in biodiversity and emissions during the lockdowns are unlikely to remain, and the situation is on course to get worse than before the pandemic. For the climate, there is historical precedent for this. There were also dips in emissions during the 2008 financial crisis, yet emissions bounced back as economies recovered.

Today, experts are concerned that global emissions in 2021 will rise beyond 2019 levels. In addition, many countries have been loosening environmental regulations and, in some countries, early recovery packages were targeted towards bailouts for oil and high-carbon infrastructure.

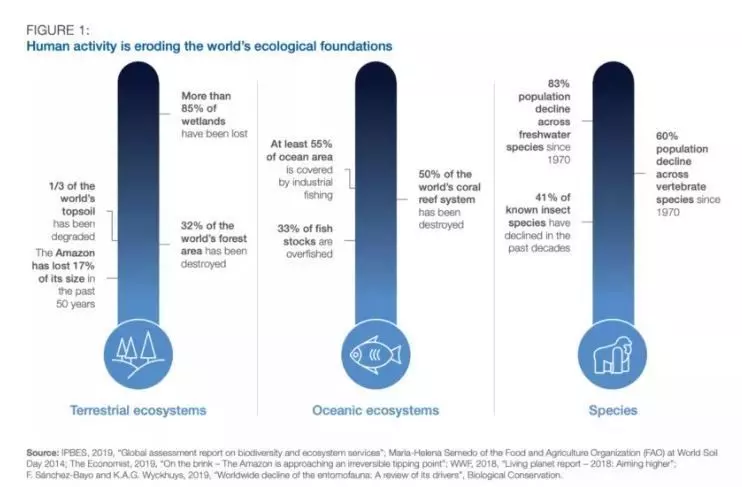

Image: World Economic Forum Nature Risk Rising

Towards a net-zero, nature-positive recovery

While the lockdowns provided a glimpse of how life could be different for our planet, this will only be the case through decisive and deliberate action. It shouldn’t take a pandemic, with devastating consequences on millions of lives, to let nature reappear and emissions drop. Rather than being good for the environment, COVID-19 only showed us how unsuitable our current socioeconomic systems are.

Some stimulus packages are acknowledging the importance of placing nature at the heart of our recovery, and in September world leaders pledged to reverse nature loss by 2030. However, on average, the pandemic is likely to reinforce negative environmental trends with stimulus packages in only seven of 25 major economies estimated to have a net positive impact for the climate and nature.

As world leaders discussed stimulus and recovery packages to keep the economy afloat, milestone global meetings to decide how to address biodiversity loss and climate change had to be postponed to 2021. These are critical opportunities to reset our economies and societies for the better. Governments and businesses must focus on addressing some of the increasingly indefensible realities of our societies and economies that this pandemic has uncovered. For example, they must ensure that economic activity is regenerative, rather than destructive, to nature, that businesses reduce their carbon footprint, and that there are sustainable, equitable jobs.

As the World Economic Forum's recent reports have found, more than half of the world’s GDP is highly or moderately dependent on nature, and opting for a nature-positive economy in key sectors could create 395 million jobs by 2030. We are likely to, therefore, pay a high price in the future for overlooking its importance in decisions made today.

Similarly, in the High Ambition Coalition's Statement on Resilient Recovery, it stressed the importance of aligning green measures from stimulus packages with climate ambitions. The UN’s 2020 Emission Gap Report highlighted that recovery investments in climate action could cut up to 25% off the emissions projected for 2030. Countries need effective policies to support zero-emissions technologies and infrastructure, reduce fossil fuel subsidies, stop new coal plants and promote nature-based solutions.

The pandemic transcended borders in more ways than one. We saw unprecedented levels of international cooperation, with information sharing and the deployment of healthcare personnel and equipment. It also taught us that, when we work together, we can enact great change. This needs to be channelled into the fight against nature loss and climate change too.

COVID-19 offered many the chance to stop and reflect on the sort of world we belong to. If nothing else, the pandemic revealed that our economies are inherently vulnerable to shocks. Images of animals reclaiming once-bustling city streets, and a dip in greenhouse gas emissions were a relief during a time of such angst, but they are exceptions that are likely to be long forgotten unless we work towards a better future. Designing net-zero, nature-positive stimulus packages is key in preventing future outbreaks, improving economic and environmental stability and enabling people to live healthier, more fulfilling lives.

*watch the video here

13 January 2021

World Economic Forum