Inside Australia's climate emergency: the air we breathe.

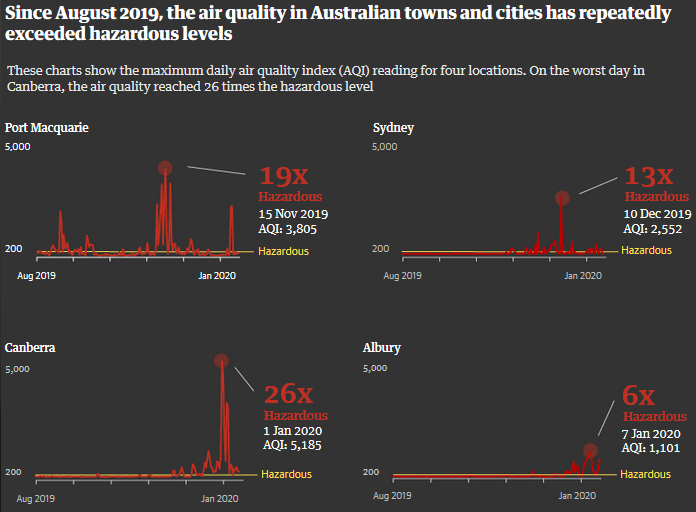

For months, Australians breathed air pollution up to 26 times above levels considered hazardous to human health. The long-term impact could be devastating.

On the worst day of the smoke, Madhumitha Janagaraja remembers watching four ambulances speed through the centre of Canberra in a single hour.

“My only thought was: how many people are going to die?” she says.

It was early January. The Australian capital had endured days of poisonous air quality. Thick smoke from fires burning in New South Wales and Victoria had rendered the city’s landmarks invisible.

On New Year’s Day in Canberra the air quality reading was the worst on the planet: 26 times levels considered hazardous to human health.

Janagaraja, a psychology student at the Australian National University, has rheumatoid arthritis. “I think for even ordinary people it makes it really hard to breathe,” she says. “But for me, when [the air pollution] increases, my levels of inflammation, my joint pain, increases massively. It gets worse every time I take a deep breath.”

By the time she asked a friend for help she had spent two days indoors, skipping meals, barely able to breathe, such was the effect of the smoke on the already inflamed joints around her rib cage.

“It’s been quite a huge loss of bodily autonomy because I’m not someone that’s very good at asking for help.”

Australia is known for its clean air. But this summer’s unprecedented fire season is changing that. Millions of people in Canberra, Sydney, and rural towns close to the fires breathed toxic pollution for months.

And experts say we don’t yet know what the long-term health effects will be.

“We’re all currently living in a big experiment,” says Donna Green, an associate professor at the University of New South Wales’ climate change research centre.

“We know it will be bad, we just don’t know how bad.”

In Sydney and Canberra, hospitals were pushed to breaking point.

David Caldicott, an emergency department doctor and senior clinical lecturer at the Australian National University, describes smoke-filled rooms, a jump in emergency respiratory cases and “many anxious parents with kids with asthma”.

The smoke that blanketed the city was so bad that it caused MRI scanners to stop working.

Donna Green has spent years studying the relationship between climate change, air pollution and human health. She says rising temperatures from climate change can increase air pollutants, such as ground level ozone.

As Australia experiences more frequent bushfires and dust storms because of climate change, we will also see an increase in air pollution, sometimes far from its original source. “We’re seeing it already and we’re going to see more of it in future,” Green says.

The most common air pollutants that are dangerous to human health are coarse and fine particulate matter (PM), nitrogen oxide, sulphur dioxide and carbon monoxide.

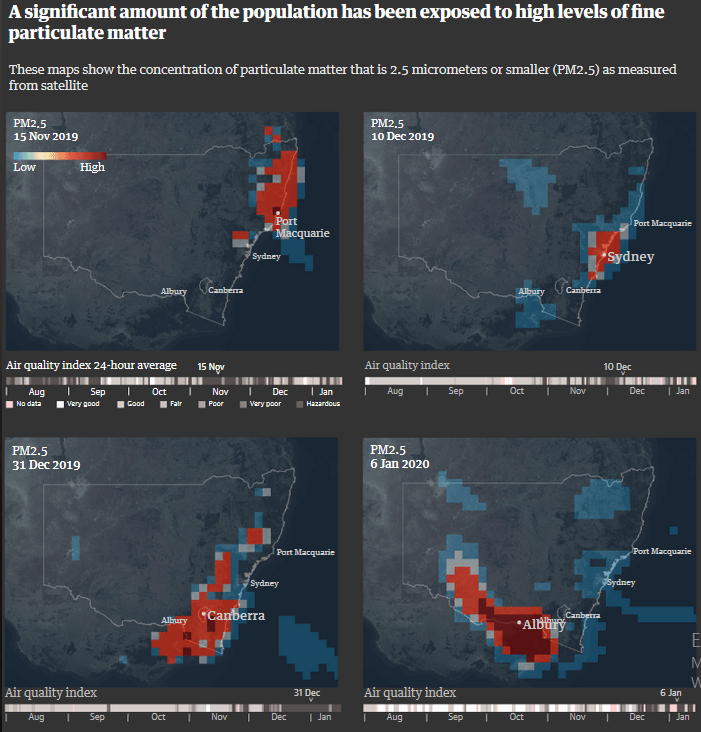

The smoke that many Australians inhaled this summer contains fine particles, known as PM 2.5, that are especially damaging because they can enter the bloodstream. “It can affect every system in your body, which means you’re not only talking about respiratory-related and heart-related problems, people are linking it to diabetes [and] dementia,” Green says.

“Air pollution has recently been linked to autoimmune diseases. The causal relationship isn’t yet known, but if it contributes only a small amount to these diseases, the overall impact on a population would be large.”

But nobody knows the impact of medium- to long-term exposure to bushfire smoke. “We haven’t had this kind of exposure before,” Green says. “People are madly scrambling now to do the studies.”

Caldicott says his greatest concerns are for children and what the cumulative effects of a decade or more of this type of pollution might be.

He says the days of troubled breathing and no sunlight in Canberra have also caused psychological trauma for many that has manifested in anxiety, nervousness and anger.

Janagaraja says the city of Canberra was ill-prepared for the crisis.

Those most in need were often the least able to reach out for help: people with disabilities, people with chronic conditions, rough sleepers, or people confined to their homes. The Australian Capital Territory government took days to make masks available for its most vulnerable residents.

Janagaraja and other students working with the students’ association organised for more than 2,000 masks to be brought in from Sydney. There was a rushed panic as the students handed them out. But even the PM2 masks are not 100% effective.

“I remember being inside at Belconnen Westfield to try and get a bit of a reprieve from the air,” she says. “And the smoke alarm started going off [inside this] massive shopping centre.”

“I came home to see the same thing, smoke alarms just going off and people had to come outside and stand in the smoke where they were coughing 10 times worse.”

“It felt really frightening to have your eyes burning, feeling unable to breathe, inside a building. There was no safe or last resort to get respite that you might have in other weather conditions.

“There was nothing we could do, with the resources that we had, to make the situation any better.”

*Read the original article here.

The Guardian