The dark secrets behind big oil’s climate pledges

Oil companies and the banks that finance them are making empty promises – and getting credit for them too

JPMorgan Chase won glowing headlines last year when the global investment bank unveiled a commitment to counter the climate crisis.

The press amplified JPMorgan’s message – sometimes in JPMorgan’s own words. Fortune published a commentary article trumpeting the bank’s plans to “tackle climate change”. Six paragraphs into the piece, the writers noted they worked for the investment firm. (They were actually its top executives.)

The bank waited months to detail its plans. In May, it finally outlined its goals: JPMorgan would not pressure oil companies to lower their emissions. Instead, the firm would encourage them to become more efficient. They would focus on their “carbon intensity”.

That metric has become a favorite of banks, oil companies and other big businesses. They’ve balked at requirements to cut overall climate pollution. But “carbon intensity” pledges have given companies a framework to keep investing in dirty fuels, while also expanding into pollution-capturing technology and cleaner energy.

“They love the metric,” said Jeanne Martin, senior manager of banking standards at ShareAction, a non-profit focused on responsible investment.

“They have committed to reducing intensity and financing to the oil and gas sector. But that doesn’t ultimately mean they will reduce oil and gas activities. It may actually increase at a faster rate.”

Such “greenwashing”, experts say, allows companies to downplay the scale of the climate crisis – and continue contributing to the problem.

“It’s the next five or 10 years that will determine our collective futures,” said Andrew Logan, oil and gas director at Ceres, the non-profit that advocates for corporate sustainability.

“It’s probably safe to say that there is no company – certainly in the financial sector, or heavy-emitting sectors – that has a fully defensible plan when it comes to meeting the scale and scope of the urgency of the climate challenge.”

World leaders are starting to find the gap between corporate rhetoric and action too glaring to ignore.

Historically, oil and gas companies have been top sponsors at international climate meetings, hosting events and prominently displaying advertisements with their climate goals.

That is beginning to shift. The UK, host of this week’s landmark climate summit in Glasgow, will limit participation by companies unless they have a “credible short-term action plan” to ratchet down emissions.

But in the run-up to this year’s negotiations, oil companies are blitzing social media with advertisements about their climate pledges.

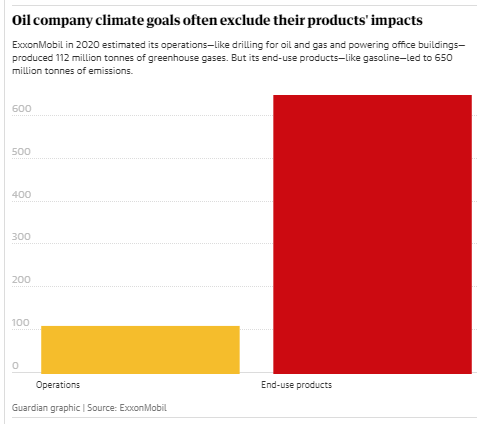

In a Facebook ad campaign launched this month, ExxonMobil promises to cut pollution from drilling. It plans to do that by reducing emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas much more potent than carbon over the short term. That will lower the “methane intensity” of its operations – but it ignores the emissions from customers burning the fuel itself.

“The fossil fuel companies feel the heat and feel the pressure to do something about this, if they want to remain the main provider of energy,” said Yamide Dagnet, the director of climate negotiations at World Resources Institute.

Royal Dutch Shell announced last week it will cut its absolute carbon emissions in half by 2030. But the commitment pertains only to the company’s internal climate footprint, not the much larger share of emissions that occur when its fuels are burned for energy. The timing of the announcement is also notable, as it comes on the heels of a Dutch court ruling earlier this year that Shell must slash its emissions 45% by 2030.

Most other fossil fuel companies – and the banks that finance them – continue to find alternatives to promising outright emissions reductions.

A net zero goal signals a company aims to offset its emissions by adding cleaner energy projects to their portfolios, or attempting to capture carbon dioxide and stop it from entering the air. But these goals can be so narrow as to be meaningless.

Beau O’Sullivan, senior communications campaigner at the global social activist group Sunrise Project*, said fossil fuel companies were “inoculating themselves from bank and shareholder pressure by making these net zero commitments”.

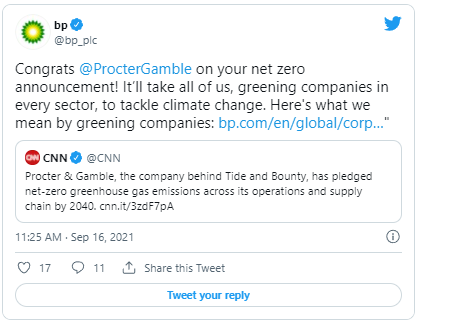

BP has the most aggressive decarbonization plans in the sector, according to an analysis by the global energy research and consultancy firm Wood Mackenzie.

The company aims to be net zero for its operations and upstream production by 2050 and to halve its carbon intensity by then. It has slashed its budget for oil exploration, and it’s the only oil giant that has promised to cut production over the next decade.

But the devil is in the details – or the lack thereof.

BP declined to comment on why it has excluded a large portion of its emissions in its net zero commitment, choosing not to calculate emissions from its more than 20% stake in the Russian company Rosneft. Rosneft explores for oil and gas in some of the most remote regions, including in ecologically vulnerable Siberia and the Arctic.

The company’s lobbying also conflicts with its climate message. In 2020, BP left three associations because of their climate positions. But it is still a member of the American Petroleum Institute, which has lobbied against electric vehicle tax breaks, methane regulations and drilling restrictions in the Arctic.

BP in a March 2021 report said it is working with API and other associations to move “on important issues such as support for the Paris Agreement, regulation of methane, carbon pricing and the role of climate science”.

These greenwashing campaigns benefit more than just the oil companies.

Banks are increasingly under pressure to drop their financing of fossil fuels. To defend their continued investments, they’re pointing at oil companies’ climate pledges.

“We’re now at a point where the very largest investors in the world, the investors who are the biggest shareholders in high-emitting companies, see climate change as a real threat to the financial health of whole sectors,” said Miguel Jaller, the vice-chair of the department of civil and environmental engineering at the University of California, Davis. Jaller was the lead author on a white paper that found intensity targets can play a role in emissions reductions, but aren’t a one-size-fits-all tool.

“Ultimately, climate change is an absolute problem that requires absolute reductions in emissions,” Jaller said.

Banks have begun to commit to shrink the carbon footprint of their own operations, including from powering their office buildings. But their biggest contributions to global heating are in the oil and gas companies they finance. Few have weaved in climate commitments with their financing strategies, although they are beginning to now.

The world’s 60 largest banks financed nearly $4tn in fossil fuel projects between 2016 and 2020, according to a March report from a coalition of climate organizations including the Rainforest Action Network (RAN), Sierra Club, BankTrack and more. That total includes lending, equity issuance and debt underwriting.

JPMorgan is the largest financier of oil and gas projects in the world, according to the report. The US-based bank poured $51bn into the sector just in 2020.

JPMorgan announced in May of this year that it would revise its lending portfolio to be more sustainable.

“We are the first large US bank to lay out concrete targets that help meet the goals of Paris – climate change is a critical issue and we want to be part of the solution, advancing sustainable and inclusive growth,” a spokesperson for JP Morgan said in a statement.

But JP Morgan’s benchmark is built around carbon intensity. The bank could finance more drilling without breaking its pledge.

The bank wants oil and gas companies to cut their operations emissions intensity 35%. It’s asking for much less from their oil and gas products – like natural gas for electricity and oil that is turned into gasoline for vehicles. For those, the bank wants a 15% reduction in intensity by 2030.

JPMorgan has said it will “work with clients to address end-use emissions, including by shifting to lower-carbon fuels and exploring other business diversification strategies.”

The main lower-carbon fuel is natural gas. If a fossil fuel company increases natural gas production enough, it could offset its emissions progress. It could keep its intensity metric lower while still increasing its overall emissions.

“They really took a page out of the oil industry book, when it comes to talking about their goals,” said Jackie Fielder, digital and communications coordinator at Stop the Money Pipeline, a coalition committed to ending the financing of fossil fuel companies.

“They talked in terms of carbon intensity. So that’s completely compatible with increased emissions.”

On the ground, JP Morgan’s financing has powered some of the most controversial fossil fuel projects. It funded TC Energy’s Coastal GasLink, a fracked-gas pipeline that in 2020 leaked in Wet’suwet’en Territory. It also financed Cheniere’s Corpus Christi natural gas export facility, as well as Enbridge, which is building the Line 3 pipeline.

A JP Morgan spokesperson said the bank focuses on helping clients “transition to the low-carbon world”, and supports climate policies like a carbon tax. But, the spokesperson added, the bank believes the world still needs oil and gas.

“The solution is not as simple as walking away from fossil fuels,” the bank’s spokesperson said.

*Sunrise Project is a Floodlight supporter.

4 November 2021

The Guardian