Coronavirus and climate change: A tale of two crises.

Coronavirus has cut emissions faster than years of climate negotiations. Does the outbreak reveal what life might be like if we were to act seriously on climate change? Or what it might be like if we don't?

China, the world's biggest greenhouse gas polluter, has no plans to cut its emissions anytime soon. Under its Paris Agreement pledges, Beijing has promised to hit peak emissions by 2030. So for the next decade, they're only going to go up.

Yet suddenly, this colossal, coal-powered economy has slashed emissions by 25%, according to numbers crunched by Lauri Myllyvirta at the University of Helsinki's Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. Not because of the climate crisis, but the COVID-19 public health emergency.

"For something like this to happen virtually overnight is very much unprecedented," Myllyvirta told DW.

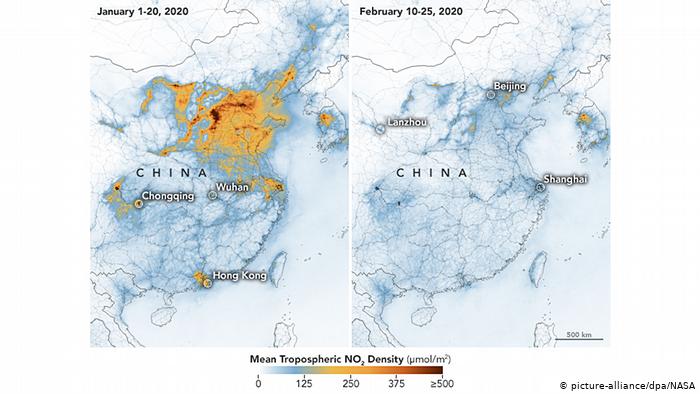

Wuhan, the 11 million-strong Hubei province city at the center of the coronavirus outbreak has been on lockdown since late January. With businesses and factories in the province shuttered, and hundreds of millions of people across the country rendered immobile by sweeping travel restrictions, the atmosphere above China in NASA satellite images appears virtually clean of nitrous oxide emissions.

Around the world, the aviation industry is predicting significant losses, British airline Flybe has collapsed, sporting events and international conferences have been cancelled, schools closed. Economists are warning of possible recession in Chinese trading partners Germany and Japan, while global growth is predicted to slow and oil demand has fallen faster than at any time since the 2008 financial crash.

All this looks like good news for the planet — at least in the short term. "Suppose you were a policymaker, and you were thinking about what you would do to lower emissions — you just got a pretty good instruction," says Amy Jaffe, director of the Council on Foreign Relations' Energy Security and Climate Change program.

Learning to localize

Jaffe says the virus is prompting us to change our habits in ways that could make a longer-term contribution to climate protection — working from home, video conferencing, working shorter weeks or staggering office hours to reduce traffic.

Companies might also conclude that what's good for the planet — localized production — is a sensible way to protect their supply chains from all kinds of risk, such as extreme weather events linked to climate change.

"They really need to go and think about all these events that could actually disrupt their supply chain and think about what they're going to do to make it more resilient," Jaffe told DW.

Still, the biggest share of emissions saved in China over recent weeks comes from the slowdown in manufacturing, and that's something few politicians would advocate as official policy beyond an immediate crisis.

Smokestack rebound?

In China, Myllyvirta says the pressure to resume business as usual is so great there have been reports of local governments ordering workerless factories to run their machines just to use up power, with the expectation that their superiors will be looking at electricity consumption as a sign of recovery.

After the 2008 financial crash, "which also led to a dramatic drop-off in China's emissions and marked improvement in air quality because export industries went into freefall," Myllyvirta says the government launched a massive, construction-heavy stimulus program that saw emissions surge.

Such stories don't bode well for the climate in a post-crisis scenario when the country is keen to get the economy back up and running.

Myllyvirta says state investment in "smokestack industries" geared to maintaining the country's growth target could see rebound emissions more than cancel out savings over the last few weeks. He hopes China might instead opt for a path of slower, "high quality" growth, based on services, household consumption and investment in green technology and renewables.

Others argue that boosting consumption always comes at a cost to the planet, and the global obsession with expanding GDP makes little more sense than running empty production plants just to get the numbers up.

A managed contraction

"The only time we see emissions significantly reduce is when countries — or the globe — goes into recession," says Jon Erickson, an ecological economist at the University of Vermont's Gund Institute who studies emerging infectious disease vectors in relation to climate change.

"These moments really point to how intimately greenhouse gas emissions are tied to economic growth," Erickson told DW.

While recessions are good for the climate, they're terrible for people — particularly those who already benefit least from our fossil-fuel economies. Among the hardest hit by China's coronavirus response are low-waged migrant workers already living precarious lives.

Yet advocates of a managed contraction of economic activity to protect the climate say shocks like the current outbreak illustrate the stark choices before us.

"We never want to do things in crisis mode," Erickson says. Instead, we have a "five to 10 year window" to "completely transform the economy so that the worst side of the contraction can be reduced, so that we can protect those who are most vulnerable."

If that sounds ridiculously optimistic, recent weeks at least suggest that when a crisis is deemed urgent enough, the world can act big and fast.

"If we truly treat climate as an emergency, as we are treating this pandemic as an emergency, we have to have a similar level of international coordination," Erickson says, starting with rapid scaling-back of fossil fuel investments.

A taste of future crises

Transmitting person-to-person and sending economic tremors across six continents, coronavirus has highlighted how closely interconnected our global community is. The ripple effect through supply chains also reveals our collective responsibility for emissions, as China's factories supply businesses and consumers in the West.

Neglecting that responsibility could mean crashes and crises far more painful than anything we've seen yet.

With a global death toll of over 3,000, COVID-19 still appears far less deadly than fossil fuels, which, according to a recent study that Myllyvirta co-authored for Greenpeace, are responsible for 4.5 million air pollution-related deaths each year, aside from climate impacts. But scientists warn that warmer, wetter conditions are increasing the probability of such outbreaks. No one knows how deadly the next one might be.

"This is an opportunity to talk about planned economic stabilization, and talk about planned degrowth," Erickson says. "The economy will contract, it will hit limits, it will crash, it will collapse on its own. That's going to hurt the most."

5 March 2020

Deutsche Welle