BlackRock has moved rapidly on climate – but Adani exposures remain a major obstacle

A glaring inconsistency in the US$10 trillion giant’s commitment to climate action

One of the successes of the COP26 summit was the growth in the UN-convened Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero to a US$130 trillion of collective assets, almost double the total of just six months ago. Enforcement of the substance of this pledge comes next. And within that, BlackRock has moved massively on the issue of climate finance.

Just two years ago IEEFA wrote about the financial costs of climate inaction for BlackRock’s investors, with the devastating wealth destruction at GE and Exxon clear examples of engagement with no time limits, transparency or consequences. Fast forward to 2021 and BlackRock clearly, repeatedly, articulates both the imperative for climate finance action and the trillion-dollar investment opportunities emerging. And a net zero pledge is pending.

Self-interest is a powerful motive, and IEEFA’s own mission is based on the need for a sustainable and profitable energy sector. There is nothing more compelling to a finance executive than a review of a decade-long pair trade (buying one asset and shorting another) – going long Tesla / short General Motors. Or long Nextera / short Exxon. Or long Orsted / short Shell. Or long Adani Green Energy / short Adani Power (more on this last one below). Investing in fossil fuels is a wealth hazard, notwithstanding the fossil fuel inflation evident in 2021, an event that is likely to accelerate investment in low volatility, domestic, cheaper, zero emissions energy alternatives.

BlackRock has clearly stepped up on engagement, public transparency, investor education, and investing in the zero emissions new industry opportunities, pushing for comparable global climate risk disclosures (the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, TCFD; Science Based Targets initiative; Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, SASB; and IFRS Accounting Standards) and even divesting (as a last resort for dinosaur industries in terminal decline i.e. coal power).

The International Energy Agency (IEA), clearly articulating for a liveable planet, made a profound pivot earlier in 2021, saying getting to net-zero emissions by 2050 means the world can’t afford any new oil, gas or coal developments. The global climate policy leadership of China, Japan and South Korea in the last 12 months has strengthened the EU’s sustained conviction, and this has been elevated by the return to the Paris Agreement of the U.S. in 2021 under President Biden, driving ambitious interim 2030 targets, reinforced by the China-U.S. Joint Declaration. The financial markets’ newfound understanding of climate risks may be evidenced by the EU emissions trading system (ETS) hitting a record high this week of €66/t, doubling in the last year, and up tenfold over five years.

BlackRock has been staunch in its insistence that divestment policies are a last resort, continuing to swim against the growing tide. There are now 180 globally significant financial institutions with formal coal divestment policies, including BlackRock itself (but only for its active debt and equity funds, and only for thermal coal mining, so one of the weakest globally). Engagement and voting can be entirely ineffective for promotor dominated firms like Adani Enterprises.

In October, Bank of China’s coal exit abroad policy sounded the death-knell for new coal power, following the exits of Japan and Korea. And China’s historic support for coal-fired power projects in developing countries is now history with the greening of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Meanwhile the groundswell to align with the IEA policy and divest all fossil fuels is building, with strong leadership from the likes of the European Investment Bank, ABP of Netherlands, AXA of France and Zurich. And when the new ADB climate policy was watered down to leave its gas policy ambiguous (thanks to Japan), we saw a very telling U.S. vote abstention against this weakness. And with the EU commitment to the necessary climate action undermined by gas industry lobbyists and wavering thanks to the Russian-EU gas crisis of late, it is great to see China stepping up as a global leader, driving for a credible green finance taxonomy.

While some in finance view divestment as a poor policy, to IEEFA this thinking ignores the growing global capital flight from fossil fuels, starting with thermal coal, but now spreading to coking coal, oil and gas. Even Wood Mackenzie now warns that the pool of climate-agnostic investors continues to shrink, elevating stranded asset risk. And the growing threat of $60bn of unfunded rehabilitation liabilities is significant enough to force even climate science denying governments to act to avoid taxpayers being left holding the can. With the growing tsunami of capital reallocation away from high emissions assets into zero emissions industries of the future, divestment is one tool to reduce growing stranded asset risks, particularly in the face of energy policy chaos.

IEEFA sees the critically important role that the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) is playing, given its pledge to align with a 1.5°C world, and interim 2030 targets. That GFANZ has grown to a US$130 trillion of collective assets (six times the size of the U.S. GDP) shows the momentum is entirely one-directional.

Having established this critical global initiative, the next imperative is to lift the bar and cull the nonsense idea that global climate laggards like Vanguard or JPMorgan Chase can be included without any decisive change in practice – something that massively diminishes the credibility of this pledge. With the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Stability Oversight Council identifying climate as a key financial risk, this adds to the weight of the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) actions to reduce investor deception from greenwash.

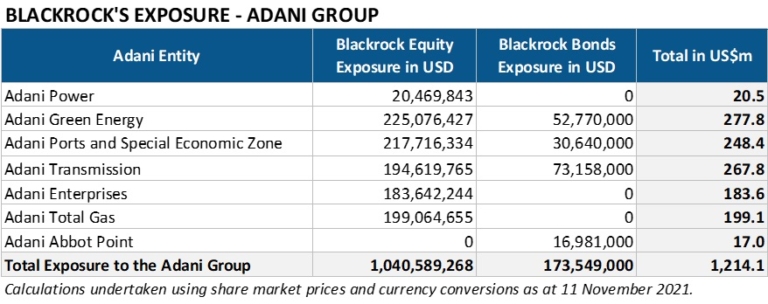

Returning to BlackRock: the bar has been raised, but some gaping inconsistencies remain. One of the starkest is the fact that BlackRock has an estimated cumulative exposure to the Adani Group of India of over US$1,200m (debt and equity). This conglomerate is possibly the largest single private developer of new coal globally, with 110Mtpa of new Indian coal mine capacity under development today. And 9GW of new coal-fired power plants, more LNG import terminals, a US$4bn imported coal-to-PVC proposal, and new gas reticulation systems throughout India.

Adani’s brand in Australia has been trashed with its unbankable Carmichael coal folly, which is due to commence exports any month now, close to a decade behind schedule, and despite repeated traditional owner objections. While the Adani Group is a clear leader in investing in zero emissions industries of the future in India, it has failed to give even a pretence of alignment with the IEA roadmap.

BlackRock argues that investing in one subsidiary is not the same as investing in another subsidiary. This is fallacious thinking when it comes to a family controlled conglomerate that has intercompany transfers as standard operating procedure. BlackRock must call out and divest global laggards at the group level, for both debt and equity exposures, not just at a subsidiary level. Hiding behind the passive excuse is greenwash, and action on changing indexes is overdue.

Investing in Adani Ports is investing in the largest private coal and LNG import infrastructure provider in India, and related party transactions are an ongoing investor issue, whilst Adani Ports, along with Adani Enterprises, has regularly invested in the controversial Carmichael mine-to-port project, which is one of the largest new thermal coal developments in the world. As a result of this and other ESG issues, S&P Dow Jones removed Adani Ports from its ESG indices in April 2021.

IEEFA has long trumpeted the developing world leadership of India’s energy transition, and how strong government policy frameworks and partnering with global capital are driving an unstoppable momentum for the decarbonisation of the Indian economy. Solar costs are half that of imported coal-fired power generation in India. India provides a clear example of how other developing countries can leverage global finance to drive both decarbonisation and technology developments so as to grow more sustainably.

Moves by corporate leaders like Tata Power and Reliance Industries’ net zero by 2035 suggest a massive acceleration in Indian ambition. Adani, on the other hand, is undermining the energy transition leadership of India with the Carmichael project and 110Mtpa of new Indian coal mine capacity under development, while also greenwashing its coal expansion with claims that the business would go “from carbon positive to carbon-neutral, and further on to carbon negative”.

We would encourage BlackRock to use its full unprecedented fiduciary power to underpin and accelerate the advances achieved at COP26, including its massive index position. When a US$10 trillion giant moves decisively, the global investor pack will follow.

By Tim Buckley, Director Energy Finance Studies Australasia, IEEFA

November 2021

IEEFA