‘Abolish these companies, get rid of them’: what would it take to break up big oil?

Communities on the frontline of the climate crisis say radical solutions must be on the table – before it’s too late

Ayisha Siddiqa doesn’t want fossil fuel companies to determine her future anymore. The industry has promoted climate denial for longer than the 22-year-old has been alive. Rather than watch companies pad their profits as the world burns, Siddiqa has a radical solution in mind.

“Abolish these oil companies, finish them, get rid of them, no more,” she said.

Siddiqa’s words echo a rallying cry for climate and environmental advocates who see limited options in finding justice for the low-income and communities of color whose lives the industry have ravaged – and will continue to as the climate crisis unfolds.

Siddiqa is the founder of Polluters Out, a youth-led coalition dedicated to removing the oil and gas industry’s influence from international climate negotiations. She created the group in response to the failed COP25 climate talks in 2019, which made little progress toward curbing carbon emissions. In her mind, the major petroleum giants don’t deserve to be involved in the clean energy revolution.

“The next stop cannot be for us to let the people who previously harmed us have a seat in the new world,” she said.

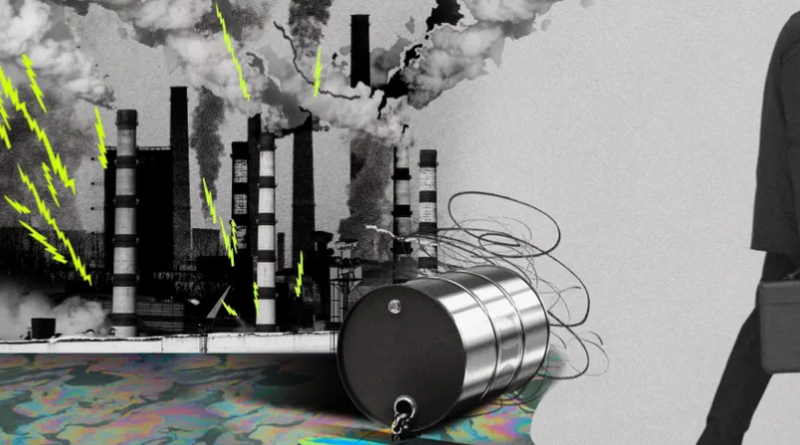

For many frontline communities, the industry’s climate crimes aren’t matters of the future. They’re here. The climate denial propaganda machine, funded by big oil and gas, has left humanity with the earth spiraling into chaos: homes crushed by wildfires, loved ones dying from heat and crops withering from drought.

In the past five years, extreme weather disasters have cost the US more than $525bn, with taxpayers footing the bill, not major carbon polluters. In 2020 alone, the global price tag tied to climate change adaptation towered at $150bn. Throughout all the damage, human lives were harmed, too. Now they’re asking: when will their voices matter?

The push to hold the industry accountable for the climate emergency by breaking up powerful companies follows a string of similar movements that have bubbled up in recent years. Ideas that were once considered fringe – like defunding police departments or busting big tech – are now filtering into mainstream discourse. And as the climate crisis increases in urgency, activists are taking aim at oil and gas companies.

Communities bearing the brunt of harm caused by climate change say that for too long the fossil fuel industry has prioritized profits over the public good. During the Texas winter storm in February, for example, gas and oil giants raked in billions by selling assets for exaggerated prices as the state struggled to provide consumers with power and heat. The state knew 10 years ago that cold temperatures could threaten the grid, but it left the decision on upgrading infrastructure up to private companies. As a result of the storm and subsequent power outages, some 700 people died, according to a BuzzFeed investigation.

Carla Skandier, manager of the climate and energy program at the Democracy Collaborative, says groups like hers are now researching ways to end the cycle of harm through nationalizing segments of the fossil fuel industry. In the simplest terms, the process would involve the federal government buying out entire oil and gas companies to take ownership of their infrastructure and assets.

“When we talk about abolishing the fossil fuel industry, we are really talking about the urgent need for an endgame to manage the industry’s fast decline,” Skandier said.

Pro-abolition groups say this process would entail putting elected officials – not corporate executives – in charge of fossil fuel assets. The US government would slowly stop drilling or buying leases as it prioritizes lowering emissions and investing in clean energy. Nationalized ownership would allow the US to leave oil and gas reserves in the ground while simultaneously shrinking the fossil fuel company’s grip on the nation.

Such public intervention would also prevent oil companies from simply shutting down operations, laying off their workers and leaving behind devastated towns and counties, as coal companies have done, Skandier said. “We need to consider that a lot of these communities are highly dependent on fossil fuel revenues, so we need to plan how we’re going to build community wealth and diversify their economies to make sure they’re not only economically stable but resilient to climate impacts in the future.”

The US could take the land or reserves currently owned by the fossil fuel industry via eminent domain, the legal right governments have to seize land or infrastructure for the public interest. The federal government has done this before to create national parks and even to convert a private energy company in Tennessee into the now publicly owned Tennessee Valley Authority during the Great Depression.

Any movement to break up big oil, however, will inevitably face enormous headwinds. The industry benefits from being deeply ingrained within American society, and it’s expected that oil and gas interests would push back hard in courts. Nationalizing profitable industries would also take an unprecedented amount of political will, which has yet to materialize.

Law expert Sean Hecht warns that breaking up energy companies may lead to unintended ripple effects. History suggests that simply erasing a company’s existence may make it easier for them to ignore their financial responsibilities when they’ve caused harm.

Hecht, the co-executive director of UCLA Law’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, saw this firsthand in Los Angeles, where he lives. When the Department of Justice shut down Exide Technologies in 2015 for illegally poisoning neighborhoods with lead for decades, the company filed for bankruptcy and left taxpayers to foot the cleanup bill.

“An industry disappearing doesn’t mean that that industry is going to necessarily be accountable, and sometimes it’s the opposite of that,” Hecht said. “It creates a sense of justice but doesn’t materially help the conditions in communities.”

A company simply signing a check may not help either, said Kyle Whyte, a professor of environment and sustainability at the University of Michigan, who also serves on the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. That won’t eliminate the root cause of the issue: companies responsible for driving the climate crisis are also stripping communities of the social, cultural and political capital to decide what happens to their homes and bodies.

“Justice would mean a world where, for example, Native people and tribes are no longer in a dependency relationship with industries,” Whyte said. “There’s no dollar amount that could be spent in a community right now that would actually replace decades and generations of violations against self-determination.”

There’s no cookie-cutter approach to rectifying what communities have inherited from big oil. And even if calls to break up the fossil fuel industry sound improbable in the current political climate, activists hope the conversation will expand the realm of possibilities for leaders to take action on climate change. For Siddiqa, any solution must also incorporate international players as well.

“We vote for our world leaders,” Siddiqa said. “They represent us. If they are actively refusing to represent us, then their position is in question.”

Siddiqa wants to see a cultural shift – a moment of political reimagination. She knows business as usual won’t stop the climate crisis – perhaps neither will the end of oil and gas – but she says it’s a good start.

This story is published as part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of news outlets strengthening coverage of the climate story.

August 2021

The Guardian