Rishi Sunak's wife owns part of firm that funnelled money through Mauritius.

The wife of the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, is a shareholder in a restaurants business that funnelled investments through a letterbox company in the tax haven of Mauritius, in a structure that could allow its backers to avoid taxes in India.

The business, International Market Management (IMM), is hoping to build a chain of dozens of restaurants across India, via franchise agreements with the celebrity chef Jamie Oliver and the American fast food brand Wendy’s.

The involvement of Sunak’s wife, Akshata Murty, has emerged from an investigation by the Guardian into a range of financial assets held by Sunak and his close family, many of which have not been declared in the official register of ministers’ interests.

Murty invested in IMM, which was set up in 2014, alongside some of the best-known names in UK hedge fund circles. Before entering parliament, Sunak worked in hedge funds, eventually co-founding the US arm of the Cayman Islands registered Thélème Partners.

IMM is chaired by David Stewart, who was previously chief executive of the fund headed by Crispin Odey, a leading backer of a no-deal Brexit.

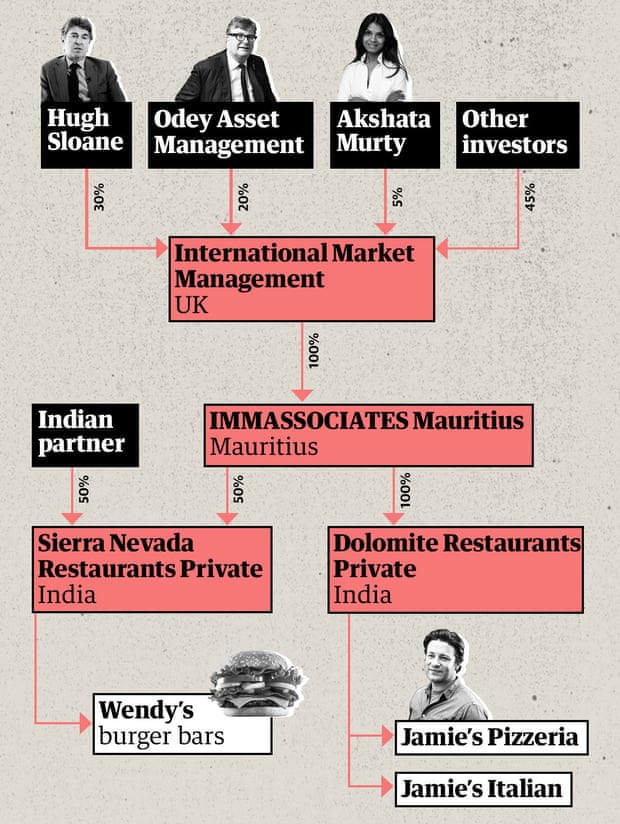

Stewart raised financing for the venture from a group of wealthy friends and acquaintances, with Odey Asset Management taking 20% of the shares and Hugh Sloane, a founder of the Sloane Robinson fund, taking a 30% share. Murty, the daughter of one of India’s best-known entrepreneurs, spent £500,000 on a 5% share, according to documents seen by the Guardian.

Each of the investors holds shares in IMM, which is a UK-registered company. Instead of investing directly in the two Indian subsidiaries that operate the restaurants, IMM funnelled the money raised from its shareholders through an intermediary company in Mauritius.

How investors routed funds via Mauritius

After reviewing the IMM structure, experts from the Indian Revenue Service and the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation, a campaign group, concluded the arrangement could reduce the taxes payable on any profits in India.

If the business is sold, there will be no tax on any capital gain in India. Had IMM invested directly, it would have been liable to pay the Indian government 20% on any capital gain, at current rates. The setup also reduces the amount of tax payable on dividends in India, from 10% to 5%.

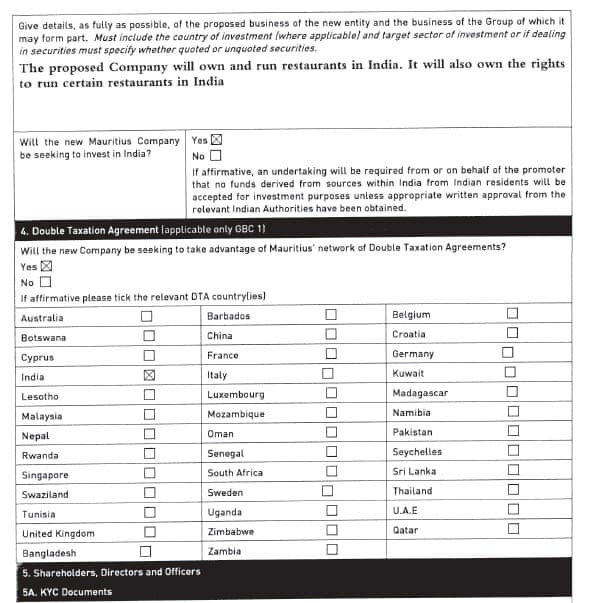

It seems IMM’s administrators were aware of the tax advantages when they set up their intermediary company, IMMASSOCIATES Mauritius, according to papers seen by the Guardian. A form filled in for the offshore services firm that acted for them asked: “Will the company be seeking to take advantage of Mauritius’ network of double taxation agreements?” IMM’s administrators ticked the box for “yes”, and the box for “India”.

The IMM chief executive, Jasper Reid, who manages the venture from New Delhi, said: “This is a standard approach to companies investing in India and is nothing out of the ordinary.” Murty and Odey Asset Management declined to comment. Sloane did not respond to a request for comment.

“If the minimising of Indian tax revenues is ‘standard’ for British investors, that’s not a justification, it’s a condemnation,” said Alex Cobham, the chief executive of the campaign group Tax Justice Network. “India needs its tax revenues for schools and hospitals. We must hope that the chancellor himself is committed to the progressive taxation of wealth and top incomes, or the UK will only see the deepening of the stark individual, racial, gender and regional inequalities that the pandemic has laid bare.”

IMM’s tax structure is legal, but controversial. The use of Mauritius as a conduit for capital into India has become notorious. A collection of islands in the Indian Ocean, with a population of 1.3 million, the small state is one of the largest sources of foreign investment into India.

By setting up letterbox companies in Mauritius – essentially shell companies with no staff and no trading activity – investors can channel money from Indian businesses to the tax haven. Investments routed through Mauritius are estimated to have cost India between $10bn and $15bn over the last 20 years in lost capital gains tax, dividends tax, and tax on interest and royalty payments.

The system has been used by foreign investors, but also by Indian nationals, who essentially send their funds on a round trip. There is no suggestion Murty was round-tripping her investment.

Murty’s family fortune comes from India, where her father co-founded the IT company Infosys. She is now resident in the UK.

“The Mauritian route to investing in India had been a reason for concern for the Indian government and civil society for decades,” said Neeti Biyani, of the non-profit Centre for Budget and Government Accountability. “This trend has caused developing countries like India to lose out on crucial revenue, that could have been used for realising human rights, funding public services and financing development.”

Tax revenues lost thanks to offshore arrangements are said to have hampered India’s ability to meet its child rights obligations. In an effort to shut down the loophole, the Indian government renegotiated its tax treaty with Mauritius last year. However, because IMM invested before 2017, it should still benefit from the terms of the previous treaty, experts said.

Any tax advantage is theoretical at the moment, as the latest company filings in India show IMM’s restaurants have yet to make a profit. The investors would also be liable for personal taxes on any income earned. In the UK, these could be as high as 38% for top-bracket earners receiving dividends.

However, the owners are optimistic. According to the latest accounts, the subsidiary operating the Wendy’s burger bars is “poised for rapid expansion”, and plans to grow to 50 outlets over the next five years.

30 November 2020

The Guardian