$10bn of precious metals dumped each year in electronic waste, says UN.

A fast growing mountain of toxic e-waste is polluting the planet and damaging health, says new report.

At least $10bn (£7.9bn) worth of gold, platinum and other precious metals are dumped every year in the growing mountain of electronic waste that is polluting the planet, according to a new UN report.

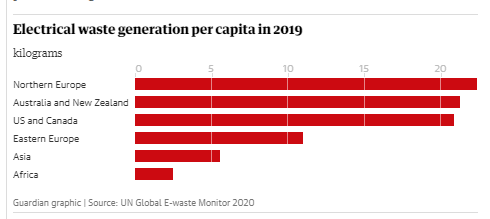

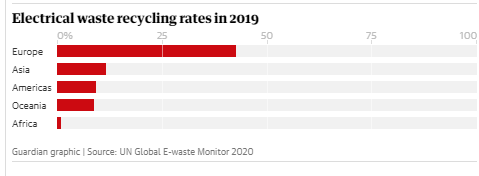

A record 54m tonnes of “e-waste” was generated worldwide in 2019, up 21% in five years, the UN’s Global E-waste Monitor report found. The 2019 figure is equivalent to 7.3kg for every man, woman and child on Earth, though use is concentrated in richer nations. The amount of e-waste is rising three times faster than the world’s population, and only 17% of it was recycled in 2019.

Electronic and electrical goods, from phones and computers to refrigerators and kettles, have become indispensable in modern societies and enhance lives. But they often contain toxic chemicals, and soaring production and waste damages human health and the environment, and fuels the climate crisis.

The report blames lack of regulation and the short lifespan of products that are hard or impossible to repair. Experts called the situation a “wholly preventable global scandal”.

People in northern Europe produced the most e-waste – 22.4kg per person in 2019. The amount was half as much in eastern Europe. Australians and New Zealanders disposed of 21.3kg per person, while in the US and Canada the figure was 20.9kg. Averages across Asia and Africa were much lower, at 5.6kg and 2.5kg per person respectively.

E-waste contains materials including copper, iron, gold, silver and platinum, which the report gives a conservative value of $57bn. But most are dumped or burned rather than being collected for recycling. Precious metals in waste are estimated to be worth $14bn, but only $4bn-worth is recovered at the moment.

Europe had the highest recycling rate in 2019, at 42%, with Asia second at 12%. But across North and South America, and Oceania, the rate was 9% and in Africa it was 0.9%.

In low- and middle-income countries, some e-waste is recycled but usually by unsafe practices, such as burning circuit boards to recover copper. This releases highly toxic metals such as mercury, lead and cadmium, “causing severe health effects to workers as well as to the children who often live and play near e-waste activities”, the report said.

It estimated that 50 tonnes of mercury from monitors, energy-saving light bulbs and other e-waste is dumped each year. Furthermore, gases released from discarded fridges and air-conditioning units were equivalent to 98m tonnes of atmospheric carbon dioxide in 2019, close to the national emissions of Belgium.

“E-waste is a very big problem because the amount is growing at a very rapid pace each year, and the level of recycling is just not keeping up pace,” said Kees Baldé at the UN University, based in Bonn, and an author of report. “It’s important to put a price on the pollution – at the moment it is simply free to pollute.”

“The biggest problem is that, in many countries, there are no collection systems,” said Mijke Hertoghs, at the UN’s International Telecommunication Union. “The companies that bring the equipment on the market are not being held accountable for the end-of-life disposal.”

But Hertoghs said the value of the metals being dumped presented an opportunity. Baldé agreed: “If [collection and recycling] were better organised, the economies of scale would go up and I think there are opportunities for creating a new economy and new jobs. There would be a huge income for many people.” Recycling would also cut the environmental impact of mining for new metal: “One gram of gold has a massive footprint.”

“Improper e-waste recycling is a major emerging hazard, silently affecting our health and that of future generations,” said Maria Neira at the World Health Organization. She said one in four childhood deaths resulted from pollution, including e-waste.

In 2018, the ITU’s governing body set a target of increasing e-waste recycling from 17% to 30% by 2023. But, as things stand, said Hertoghs: “It’s totally unrealistic to achieve that goal.” Since 2014, the number of countries with national e-waste policies or laws in place has only increased from 61 to 78, out of a total of 193 UN member states.

Libby Peake from the thinktank Green Alliance said: “The ever-growing mountain of e-waste documented in this report represents a wholly preventable global scandal.

“It doesn’t have to be this way,” she said. “Products could be designed to last, to be repaired and, just as crucially, to be upgraded. Ensuring the system keeps electronic products in circulation would create hundreds of thousands of jobs … There’s no excuse for leaving this scandal unaddressed.”

2 July 2020

The Guardian