Forest fire season is coming. How can we stop the Amazon burning?

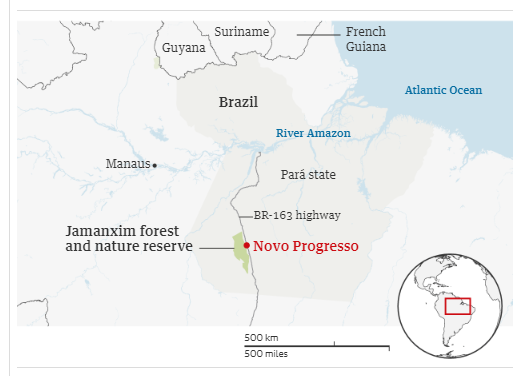

We found the first fire without looking, crackling and roaring on farmland beside the busy Amazon highway, the flames consuming a road sign with its name – BR-163 – lying in the grass. Trucks thundered past, ferrying soya and corn from the agricultural heartlands of Brazil’s central-west to the ports of Santarém and Miritituba. Nobody was around.

Every year fires roar across the Amazon, and in just a few months they will be here again. But last August the number of blazes reached a nine-year high, and sparked an international crisis for Brazil’s far-right president Jair Bolsonaro. Months later, their traces hung over the forests in the Amazon state of Pará, leaving blackened logs and charred tree stumps where there was once rainforest.

But what happens to the land afterwards, especially in protected reserves? Is anyone punished for burning the forests? Are the forests allowed to grow back? Most of all, what can we expect from this year’s fire season? Late last year, reporters from the Guardian and investigative site Réporter Brasil spent a week at reserves along the BR-163 to find out.

We started in the hardscrabble settlers’ town of Novo Progresso in the state of Pará, with its plethora of gold shops serving the largely-illegal wildcat mining trade. Police are still investigating Novo Progresso farmers for allegedly coordinating a “fire day” last August to show Bolsonaro their will to work – fires soared by 300% around the town that day. The town sits beside the Jamanxim national forest, a protected reserve of more than 1.3 million hectares (3 million acres) that is one of the most devastated in Brazil. Where better to begin?

Rapacious history

The first morning we steered the rented 4x4 along a dirt road out of Novo Progresso, bouncing over potholes as it snaked in and out of the Jamanxim forest. This forest is managed by the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), a federal environment agency named after the rubber tapper, activist and environmentalist who won international acclaim before being murdered in 1988 by cattle ranchers.

Inside Jamanxim’s borders, as forest gave way to a sweep of cattle farms, we found more fire: a patch of forest still smouldering in places, trees swiped at waist height, and the felled, blackened trunk of a regal brazil nut tree in the scorched earth. An extensive search of government websites, publicly available information and internal ICMBio documents revealed that this very patch of forest has an emblematic history of environmental offences and fires.

This smouldering land fell inside the 889 hectares of land registered in 2015 by Jair Ferreira de Souza, a Novo Progresso resident, on Pará state government’s Rural Register (CAR), just inside the borders of the Jamanxim forest. In 2017 and 2018 Nasa satellites spotted fires on this land, and in 2015 and 2019 De Souza was fined more than £500,000 for destroying hundreds of acres within it by environment officials who photographed cattle branded with his initials: JF.

De Souza has appealed the fines, none of which have been paid. He told officials that he needed pasture and denied that one patch of destroyed forest was his. He claimed his family had owned land here for 30 years, arguing that he had cleared only a minimal area he needed to work, and requested one fine be annulled because he was unable to pay it.

Souza did not respond to messages sent to his phone.

But to understand how Jair Ferreira de Souza is able to claim ownership of land within a federally protected forest, we need to step back into the Amazon’s chaotic and rapacious history of colonisation.

The landgrabbers

The military dictatorship that ruled Brazil until 1985 – often lauded by Bolsonaro - encouraged migration and built highways to force development into the Amazon region, but failed to impose a functioning property system. Instead, it sold off chunks of forest – then largely government owned – to private investors. It also handed out lots to migrants who had been encouraged to move there from the poorer north-east.

Much of this land was sold on later, often in deals involving unscrupulous notaries in a range of scams that continue until today, aided by the remoteness and lawlessness of the Amazon region. Adding to the disorder, under Brazilian law, improving land you are on can strengthen an eventual ownership claim. And Amazon farmers often argue that previous governments had encouraged them to move to the region, only to plonk a reserve on top of them years later even if they actually squatted the land afterwards.

“As long as it’s confusing, as long it’s undetermined who owns what, the guys with the lawyers, the guys with the guns and the influence always win,” said Jeremy Campbell, an associate professor of anthropology at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island, who specialises in Amazon land conflicts.

Landgrabbers – nicknamed grileiros, or crickets, after the tested ruse of leaving fake land titles in drawers full of the insects whose secretions turn them yellow and convincingly old-looking – proliferate in the Amazon.

Having some sort of document is key to eventually legitimising stolen land. These days farmers register their own land online – as was done for de Souza – but often there is more than one claimant for the same area. In Pará, there are around three times as many land titles as there is land, state prosecutor Jane Souza said in an interview. In December, Bolsonaro signed a measure allowing grileiros to claim up to 2,500 hectares (6,177 acres) of land squatted before 2018 under certain conditions, such as no environmental fines or embargoes. This needs to be approved by Congress.

The Jamanxim national forest reserve we were in was created in 2006 to slow rampant deforestation. Farms in the reserve were supposed to be repossessed by the government, but that never happened. Commercial agriculture is not permitted there but many local people have never accepted its reserve status.

Paulo Moreira, a federal prosecutor in Pará, explained in an interview that protected areas like Jamanxim are attractive to speculators who buy illegally cleared land cheaply to sell on, or deforest it themselves, betting it will be regularised in the future and increase in value. “Crime compensates – and that makes it attractive,” Moreira said.

We spoke to residents of Novo Progresso who clearly saw themselves as hard-working pioneers in a hostile wilderness. “Wood, gold prospecting and now cattle made this town,” Jadir Rosa told us. The 36-year-old mechanic had moved from Paraná state in the south of Brazil and was lunching in the town’s market. Rosa supported Bolsonaro and shared his government’s scepticism over climate science. “Global warming does not exist,” he said.

Other residents similarly harboured little sympathy for environment officials. Laudi da Silva, a 72-year-old market stall holder and Bolsonaro supporter, complained that her brother’s wildcat mining barge had been destroyed during an operation by environment officials. “They’re always burning things round here,” she said. “I don’t like it.”

Agamenon Menezes, the influential president of the town’s rural producers’ union, has been interviewed by police in connection with the “fire day” investigation, and his computer seized, but he denied involvement during an interview at his union’s headquarters. He argued that “fire day” had been invented by the media to attack Bolsonaro and that there were no more fires last August than in any other year. He denied man-made climate change existed because, he said, 35,000 “serious” Brazilian scientists had disproved it.

Menezes said Bolsonaro was popular in the region because he was against environmental officials and regulations preventing people working. “They have to eat, they have to produce food. So they work illegally,” he said. “Nobody wants to be illegal as well. They want to work legally.” Fires were lit to clear land for pasture that is then turned into agricultural land, he explained. “You get an area of dense forest and deforest it,” he said. “You need to burn this wood.”

Environmentalists describe a similar deforestation process. First, landgrabbers and loggers remove the most valuable trees, leaving some cover to make it harder for satellites to spot the damage. The remaining trees are then felled, left to dry and burned – hence the fires. Later grass is sown, and cattle put on the deforested land to consolidate possession.

This is “the classic cycle we have seen in recent years”, said Greenpeace Brazil’s senior forest campaigner, Adriana Charoux. If the farmer feels confident enough about his ownership of the land, the next stage is soya, she added.

Soya production is growing in the Novo Progresso area, Menezes said, taking pride in the region’s improving productivity.

The firefighters saving the forest

It was striking to see how farming had eaten into the forest on both sides of the BR-163. Cows were everywhere. Wildlife survived as best it could. One morning a white monkey scuttled across a dirt road, followed by a gaggle of forest pigs. Black, blue and orange macaws squawked atop a charred tree trunk, their only perch in a field of cattle. An opportunistic anteater darted across the highway in a gap between the trucks.

All along the highway were signs of logging, including an enormous sawmill at Moraes Almeida and three clapped-out flatbed trucks parked up one morning without licence plates by a smaller sawmill at Vila Izol. Nearby were three swastikas daubed on a bar door. Logging was also evident in the Serra do Cachimbo Springs reserve – a 342,000 hectare “biological reserve” created in 2005, which is also run by ICMBio.

Driving down a dirt road in the reserve one morning we passed a man standing next to a motorbike as a lookout while chainsaws howled in the trees. It was a tense moment: environment officials warned that running into loggers in reserves, who are often armed, can be risky.

When a convoy of government firefighters in 4x4s hurtled past, we followed them into a 6,000-hectare farm registered on the CAR system in 2016 to André Ferri. Cattle grazed on pasture littered with old charred logs outside an empty farmhouse, surrounded by a curtain of forest.

“All of this was burned, and this is a sensitive area,” said one of the firefighters, speaking anonymously because Bolsonaro’s government has banned environment agency employees from talking to the media.

A few miles from here, a thousand hectares of Ferri’s farm was embargoed by ICMBio officials in April 2015 after being destroyed illegally and he was fined £3m. Four months later officials revisited the area and found the area had been burned and the area of devastation increased by more than 400 hectares. A satellite image from 2005, when the reserve was created, found no deforestation in the embargoed areas. In 2017, Nasa satellites found fires around the same area. The farm’s limits have since been modified on the CAR system to exclude the embargoed area.

Ferri has accumulated millions of pounds in fines, some of which were handed out after he broke previous embargoes and none of which has been paid. The neighbouring farm is owned by a transport company run by his brother Edner in Paraná state where André Ferri is also believed to live. Reached by phone on a Paraná number, he refused to answer questions. Brazil’s justice system has been unable to locate him to formally notify him of any of his fines.

The firefighters headed deeper into the reserve to check an area that had been flagged for deforestation by satellites. Near a patch of houses there were freshly felled trees but no flames – yet. They raced off again, passing a charred clump of felled forest, over a rocky ridge and through more cattle farms before parking near a clearing pockmarked with blackened logs and trunks.

Officials first came here last August following a deforestation alert and found a wooden house under construction, which they destroyed. Days later, the area was set on fire. The flames spread for miles and firefighters took days to bring the blaze under control. “This is an enormous loss for the environment,” one firefighter said. “It will take hundreds of years to recover.”

As the fires raged, a woman calling herself Nair Brizola drove up to Brazilian reporters and told them that ICMBio officials had started it. Her story was widely circulated by Bolsonaro supporters and the president ordered an investigation. In 2015, nearly 2,000 hectares of land including the scorched clearing where we stood was registered on the CAR system under the name Nair Rodrigues Petry. They are the same person. As Nair Brizola, Petry stood for the council of a town 150km away and had offered a similar plot of land for sale on Facebook for around £500,000.

Brizola/Petry has since been fined £221,000 for destroying 71 hectares of forest using fire. In a telephone interview on the same mobile phone number that appeared on the Facebook land sale advert, Petry said she had documents proving the land had been hers since 2001. “When they came and created this reserve, we were already there,” she said. “Nobody is a crook.” She repeated her accusation that ICMBio officials had started the fire, denied offering the land for sale – and has not paid the fine.

Petry said she was only just beginning to “mess” with the land. “In the future, the only thing we could do is pasture,” she said, meaning more cattle. “If I leave there, and leave it all abandoned, someone else will go in.”

How ‘cattle laundering’ fuels the fires

Brazilian meat companies have complex systems in place to prevent them buying from Amazon farmers facing fines and embargoes, like André Ferri. But farmers can avoid those checks by selling cattle to other farms for fattening, who then sell on to slaughterhouses – a triangulation process some environmentalists have dubbed “cattle laundering”. Pressure is growing on meat companies that are largely unable to monitor all their “indirect suppliers”. In the case of one company, Marfrig, “indirect suppliers” provide more than half of its cattle supplied from the Amazon.

Research by Holly Gibbs, a professor of geography at the University of Wisconsin who monitors Amazon cattle supply chains, has found that from 2017–2019 there were at least a hundred properties in the Jamanxim forest raising cattle – 68 of them indirect suppliers. Gibbs’s team found another 27 properties in Serra do Cachimbo involved in cattle production from 2017–2019, including 25 that were indirect suppliers.

We had our answers: the farms we had managed to reach had illustrated the whole process. Fires – three times more common in Amazon cattle farming areas – are used to clear forest for pasture. Fragile law enforcement means fines are ignored. And when the loopholes that allow farmers to sell cattle raised on illegally burned or deforested land are taken into account, the future for Novo Progresso’s forests is not bright. Instead, it is black with smoke.

It was dark when the firefighters’ convoy left, bouncing back down dirt tracks. A huge fire lit up the night sky: Petry’s neighbours burning more trees, the firefighters said. It was dark, and there was nothing they could do. We know why Amazon forests like this burn, but given Brazil’s current political situation, there are no solutions in view.

5 May 2020

The Guardian