How Cop25 turned its back on climate action

The final text released after a marathon talks harked back to a deal made in Paris that placed no requirement on most countries to raise their targets until 2025

It was Cop25’s final call to arms on climate action.

A globally-agreed commitment, delivered after the longest climate conference in history, looked ahead to 2020 and raised “serious concern” about “the significant gap” between what countries have pledged and what scientists say will stop the planet warming.

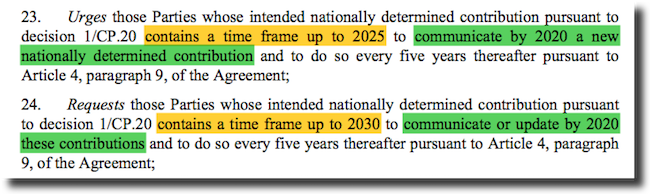

The Chilean presidency of the Madrid talks had made “ambition” a central aim for the meeting. But the text they drafted lacked a clear call for countries to raise their game on a specific time frame. Instead, it harked back to an obscure part of the deal cut in Paris in 2015: ‘1/CP.21’, specifically paragraphs 23 and 24 (below).

These two paragraphs, which were drafted alongside the Paris Agreement in the cauldron of the 2015 talks, are the only piece of international law governing the 2020 push for greater action. But they place no legal requirement on most countries to step up in 2020, according to climate jurists.

Kenyan climate campaigner Mohamad Adow called the Madrid outcome “disastrous, profoundly distressing”.

“We cannot just copy and paste the text from four years ago. We need to recognise that since then the climate emergency has got worse and public anger has got fiercer,” he said.

Without clear action in 2020, the first concrete moment for nations to step up their national climate commitments (known as nationally determined contributions, or NDCs) under the Paris Agreement is not until 2025. That is more than half the time left before the carbon budget for 1.5C is blown at current emissions – see Glen Peters’ graphic below.

To try to speed things up, some governments, the UN and climate campaigners are pushing for a collective raising of ambition during 2020. Advocates insist all countries are obliged by international agreement to raise their voluntary Paris pledges by 2020.

Scientists are clear on the need for increased, near term action to halt warming and prevent large-scale human suffering. But countries’ legal responsibilities in 2020 – centred on the two paragraphs agreed in Paris – are clear and separate from other imperatives, according to Sue Biniaz, who was the US state department lead climate lawyer for nearly three decades and had a hand in drafting parts of the Paris text.

She told CHN that, for most countries “there is no requirement to up your NDC in 2020”, adding “I have been saying that the science, rather than Paris per se, is why parties should enhance their NDCs.”

The two paragraphs each contain two key elements: they differentiate between countries that set an emissions target for 2025 and those with a goal stretching to 2030 (in yellow above); and they place different requirements on these countries for 2020 (green).

The different requirements are critical. Nations that set a 2025 target are asked to present a new NDC. Under the Paris Agreement any new or updated NDC must represent a “progression”. So these nations really have to bring new and improved pledges in the next 12 months. Nations that set a 2030 goal have a choice: to “communicate or update”.

Who are the countries that fall into the first group? The US dominates the list in terms of emissions, but is leaving the Paris Agreement before the end of 2020 and won’t be updating its NDC. Brazil is also in this category, and while its current government has flirted with following Trump out of the pact, remains in Paris.

The other 13 countries that set only a 2025 target in their pledge to the Paris Agreement account for around one quarter of one percent of global emissions. They are: Ecuador, Congo, Gabon, El Salvador, Suriname, Guyana, Belize, Micronesia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, Niue, Palau, Tuvalu.

The rest – including all the big non-US emitters – are covered by paragraph 24.

Biniaz said: “The Paris decision requests parties with 2025 targets (such as the US) to submit their next NDC in 2020 and parties with 2030 targets to either update them or recommunicate them in 2020.

“We included ‘recommunicate’ on the theory that a party might think twice about sticking to an unambitious target if it had to affirmatively repeat it, rather than just kick back and silently keep it. I have been saying that the science, rather than Paris per se, is why parties should enhance their NDCs.”

CHN spoke with several active climate diplomats regarding this issue; they confirmed there was no legal requirement for new NDCs in 2020 but didn’t want to speak on record because while the letter of the law appears clear, the issue remains contested.

Champions of higher ambition argue that other aspects of the decisions taken in Paris should be considered. They argue that the overarching goals set in Paris – to limit warming “well below 2C” and try to halt it at 1.5C – compel countries to do what is necessary to reach them.

Bill Hare, an Australian climate scientist and veteran watcher of the UN climate convention (UNFCCC), told CHN on Twitter: “The full context of the UNFCCC decisions in Paris, which Australia supported, provide deeper background to the requirement to submit more ambitious NDCs by 2020.” (This issue is particularly pointed in Australia, where the government has already ruled out enhancing its NDC next year).

Hare said another deal made in Paris – the request to IPCC scientists to report on the steps needed to limit warming to 1.5C – was also relevant.

“The IPCC’s special report on 1.5C confirmed very clearly that unless there is substantial improvement in the NDC’s and their emission commitments for 2030 but it will be very difficult, if not impossible to meet the Paris agreement long-term temperature goal,” he said.

Halldór Thorgeirsson, who chairs Iceland’s climate council but was previously a senior director at the UN climate secretariat, said it was “not helpful to look at elements of the logic of Paris in isolation”.

“NDCs are a contribution to the objective to stabilise the climate and it was well understood that they would need to become more significant with time,” he said. “It is crystal clear that we are not on track but can get on track with political leadership and focus. There is even greater need for global unity of purpose and push for ambition now than in Paris in 2015.”

The Madrid outcome weakens this argument by focusing narrowly on paragraphs 23 and 24, rather than updating them to match the new evidence provided by scientists.

“This deal rips out the most important part of the Paris Agreement – its requirement for countries to revise and update their climate plans next year,” said Adow, who is the director of Power Shift Africa. “That regular review and ratchet mechanism was what promised to make the Paris Agreement an effective tool for reducing emissions. It is this which makes it such a powerful law to prevent climate disaster.

“But in Madrid, governments have turned their backs on raising ambition, at a time when we need more than ever to heed the scientific warning – act now or pay a terrible price later.”

PHOTO : Kenyan activist Mohamed Adow (background wearing hat) gives a furious press conference during the final phase of talks in Madrid. He later called the result of the talks “disastrous, profoundly distressing” (Photo: IISD/ENB - Kiara Worth)