Coal is destroying South Africa. Renewables are the future.

Eskom is too big to fail. The fate of the power utility and the fate of this country are one and the same. And right now plans to rescue Eskom lie in doubling down on its coal-fired power plants, on a fleet that can — on a day without load-shedding — only provide about 70% of its own capacity.

We are not making this up. This is what the government itself has said.

But, as the Mail & Guardian has reported throughout this year, coal no longer makes sense. It pollutes rivers and fills our lungs with poison. It doesn’t seem to work when it rains, or when it’s too hot. It is the source of massive corruption, state capture and patronage networks that go all the way to the leadership of this country. It drives the climate crisis, which is already destroying communities and threatens to undo all the achievements of this democratic country. Coal is also unaffordable, and as the president noted this week, banks will not finance it.

At a press conference after a meeting with Eskom top brass, Cyril Ramaphosa, who returned early from a visit to Egypt, mostly appeared to suggest that Eskom somehow had to do better, that it should put together some kind of emergency plan — as if it has not been in a state of emergency for some time now.

This is out of touch with reality.

Our national energy plan, global commitments, basic common sense and duty to the people living under the shadow of coal power plants say we need to shift to a mix of renewable energy sources.

At this point, the only reason we are dithering is our political order. Some ministers seem unable to think of a world where the myth of “coal baseload” does not hold true. Others understand that the murky world of coal contracts means they can continue to loot the public purse. Let us not forget that the failure of Medupi — our R200-billion power plant that still struggles to produce electricity — is partially down to boiler contracts that the ANC benefited from.

These considerations are destroying our today and stealing our tomorrow. Given the failure of our state and this unprecedented crisis, the M&G has brought together our team of business, environment and investigative reporters to look at how things got this dim, why they remain awful and what needs to illuminate the path forward.

The historic crisis

Medupi — Eskom’s newest and “cleanest” power plant — kills 1.4 people per year, with a further 144 people hospitalised from breathing in the polluted air that it releases, according to internal documents. The coal mines that supply it do more damage. But their numbers are secret.

Eskom says the pollution from its whole fleet kills 333 people a year — and that’s a conservative estimate. This costs the economy R17.6-billion each year in lost productivity or families left without a breadwinner.

In Mpumalanga, where most of Eskom’s power plants operate, the utility’s documents show that 117 000 people a year end up in hospital because of its air pollution. That cost to the healthcare system is unknown, because the health department doesn’t collect data on it. This is despite air pollution from all sources killing 20 000 people a year in this country, says the United Nations. Caring for these people is, in effect, a secret subsidy to Eskom. As are the asthma pumps and other medication that people living in Mpumalanga have to buy to keep breathing.

These numbers do not end up in speeches by ministers. They are not brought up when calculations are done about what should power this country.

In defence of its pollution, Eskom has previously told the M&G that it doesn’t find the conversation about dead people “constructive”. It has also argued that by providing electricity, it prevents people from burning wood and coal in their homes, which also pollutes and kills.

That argument no longer holds when there are clean sources of energy available.

To try to force Eskom, and industry as a whole, to urgently consider people’s health, the environment department created air quality regulations. These set limits for pollutants, which become more stringent over time, allowing polluters room to invest in cleaner factories. Eskom was involved in the drafting of these limits, so has now had nearly two decades to clean up its act. Instead, just this month it asked for permission to ignore these laws, in effect turning a blind eye to killing people.

Its argument is that compliance — to the tune of R200-billion — would cost too much.

There is also Eskom’s effect on the climate crisis. The utility alone emits about 40% of South Africa’s greenhouse gases. It is the largest polluter on the African continent, by far.

This country’s commitment to lower carbon emissions, as part of the Paris Climate Change Agreement, is based almost entirely on what happens at Eskom.

But that pledge is based on numbers from 2009. Climate scientists have since said global carbon emissions have to drop by 45% by 2030 and to net zero by 2050. If this doesn’t happen, the world will warm to levels where modern civilisation will collapse.

Those with less will be hit most. This continent will be hit the hardest, after island states that are already vanishing below the waves. In climate negotiations, South Africa continues to push for more ambition on reducing carbon emissions around the world. But even the new national energy plan — the Integrated Resource Plan 2019 (IRP) — doesn’t come anywhere near a 45% drop in emissions.

Moving to renewable energy would change this and save the lives of hundreds each year.

The current crisis

We got a first-hand glimpse this week at what an energy and climate-constrained future looks like. It wasn’t pretty.

Non-stop rain on the highveld — where Eskom runs its coal-fired fleet — brought heavy flooding. The utility, which struggles to keep the lights on in ideal conditions, announced unprecedented stage six load shedding. Less than half of Eskom’s 40 000 megawatts of capacity was able to produce electricity. Municipalities such as Johannesburg scrambled because they didn’t have this stage in their planning. Eskom blamed wet coal and conveyor breakdowns. President Ramaphosa later also blamed sabotage.

The result was both outrage and confusion as mines shut down, small businesses were forced to send workers home and hundreds of thousands were stuck in grid-locked traffic because robots were out.

This almost certainly pushed the teetering economy into a recession, putting further strain on an already tight fiscus.

The rolling power cuts also threatened the country’s telecommunications networks.

So, this week, large parts of the country faced floods (or drought), no power and limited communications.

Eskom insiders dismissed the president’s claim that the worst bout of load-shedding was because of acts of sabotage at Tutuka power station, where three units were out of action, leading to a loss of 2 100MW of power.

“In fact, at the time we were on stage six, Tutuka was running with five out of its six units, making it a good contributor to the grid,” said one insider, pointing instead to systemic failures behind the crisis.

“The problem here is that poor planning and lack of maintenance were largely to blame for this. Adverse weather is something we can have prior knowledge of and plan around.”

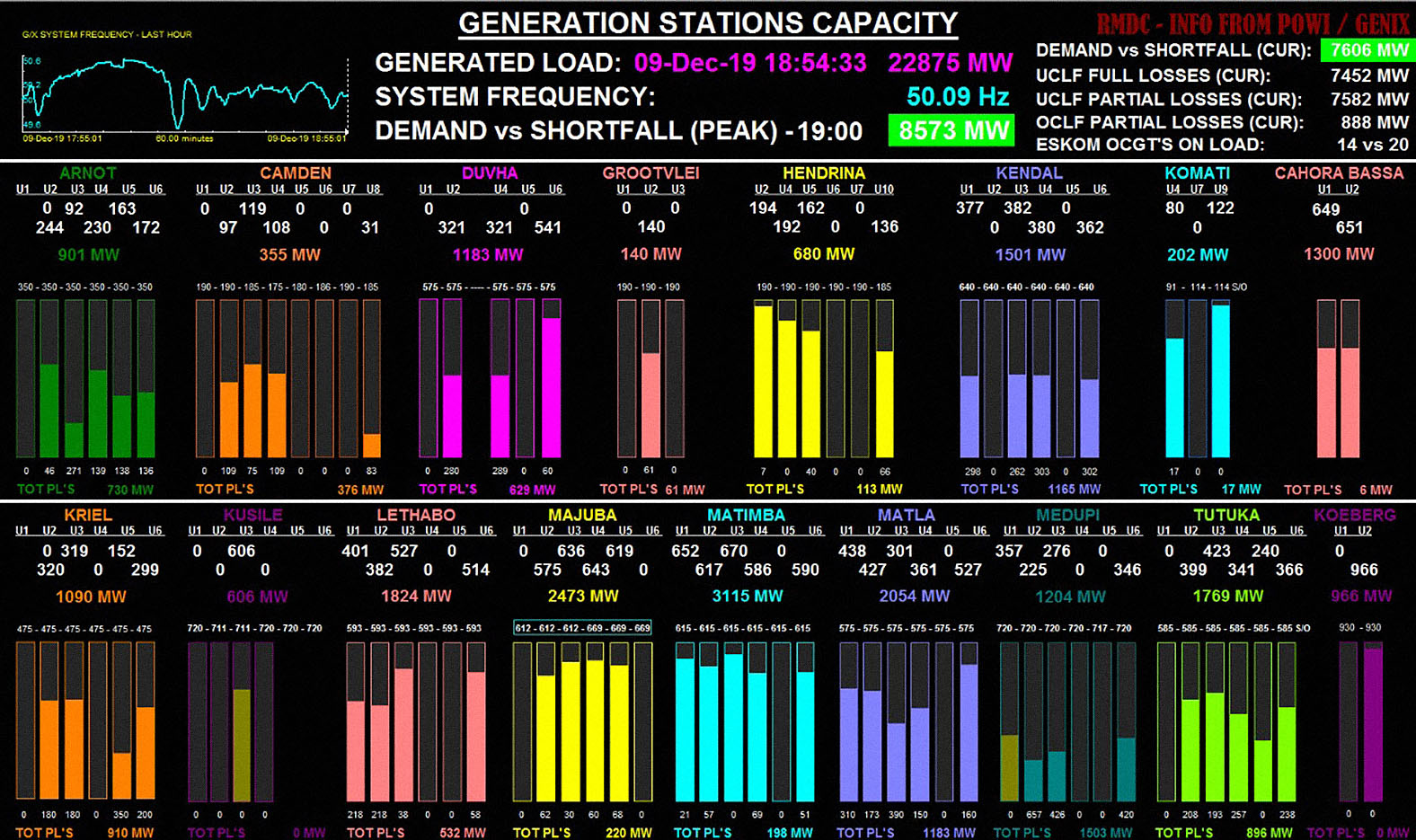

The M&G has learnt that, on Monday — when Eskom announced for the first time that losses of generating power necessitated for up to 6 000MW to be load-shed from the grid — it had units at eight stations out. This was in addition to several units that were down for maintenance, according to an Eskom engineer.

Stations out included:

• Camden — wet coal and high load losses because of water ingress on the turbine house (flooding);

• Kendall — Units two (686MW) and six (686MW) were out, whereas another four units were running at low capacity because of wet coal;

• Duvha — only two of its six units were running;

• Kusile — zero units running;

• Medupi — zero units running;

• Matla — lost 1 183MW through one unit because of boiler tube leaks;

• Kriel — 910MW through high load losses because of wet coal;and

• Arnot — lost 730MW through high load losses because of wet coal.

The remedies

After clawing back, the utility said it needed a cushion of 5 000MW to keep the grid running with some sort of stability in the future.

This is truly remarkable because, as recently as October — when energy minister Gwede Mantashe released the much-delayed IRP — he said that 2 000 to 3 000 additional megawatts were urgently needed.

The IRP has been delayed for nearly a decade. Meant to be updated every two years, its 2013 and 2015 updates were thrown in the dustbin by former president Jacob Zuma. This is because the plan said South Africa did not need nuclear energy — a R1-trillion build that Zuma was hell-bent on getting done. Instead, those updates outlined how the country should shift away from coal and nuclear to create a mixed grid, dominated by wind and solar power plants.

This year’s edition of the plan, which has been signed off by the Cabinet, put urgency at the top of a list of nine priorities. That urgency would be achieved, it said, through new power plants: “Undertake a power purchase programme to assist with the acquisition of capacity needed to supplement Eskom’s declining plant performance and to reduce the extensive utilisation of diesel-peaking generators in the immediate to medium term. Lead time is … the key.”

That lead time would exist had the previous administration not stalled the entire renewable energy programme. Eskom exacerbated this further by refusing to sign agreements with wind and solar power plants to buy their electricity, despite their contractual obligations to do so.

This has set back the whole industry. So, instead of factories building wind turbines and solar panels at scale, much of this technology has to be imported.

As the M&G has reported, the focus on nuclear — much like the focus on coal power plants — is because large-scale energy allows for large-scale corruption. A R200-billion power plant comes with myriad contracts and moving parts, each one of which can be profited from.

Renewable energy comes in small projects; in the form of a 100MW wind farm in the Eastern Cape and a 50MW solar plant in the Northern Cape. Put together, they build a national grid.

These projects have to bid for the right to supply power, in an open bidding process. All of this makes theft difficult.

Renewable energy also means shaking up the existing Eskom monopoly.

Adjunct professor Michael Sachs, at Wits University’s Southern Centre for Inequality Studies, believes that there should be different kinds of energy allowed in the country and more opportunities created, instead of focusing only on coal and Eskom.

“I wouldn’t say we should explicitly go one way or the other because there is space for many different opportunities, for as many people as possible to invest in energy; we shouldn’t block any of them. The other thing that people mix up is that it is commonly assumed that what is good for Eskom is good for South Africa.

“We have to look beyond that and say how do we grow the economy? That is where we need to build a different power system than the one we have now.”

Sachs, who is a former national treasury deputy director-general of the budget office also says that in terms of technology advancement, climate change and industry, renewable energy is becoming much more attractive.

The renewables industry has responded to the crisis by saying it could meet the shortfall in as little as 12 months, but this can only happen when Mantashe, who has unique powers to do this, signs off on contracts to source this new power.

But, having identified the need in his own IRP, Mantashe has not signed such determinations, even though experts have been warning for months that the crisis is worsening. This week his department produced a press release saying he would sign determinations to source new power.

Apparently under pressure from the imploding energy sector, Mantashe said he was not the minister responsible for Eskom.

But there are several, immediate things that the minister could do to free up more electricity. These range from amending schedule two of the Electricity Regulation Act, which would allow users to produce up to 10MW of their own electricity and to give municipalities permission to buy electricity directly from independent power producers (IPPs). It is estimated that this would take 1 300MW of pressure off Eskom, with mines and intensive users generating their own power.

Mantashe is aware of all of this, said Kevin Mileham, the Democratic Alliance’s spokesperson on energy. “But he is trapped in an ideological box of his own creation, and appears unwilling to take the necessary steps to get power flowing to South Africa again.”

Jo Dean of the South African Renewable Energy Council (Sarec), which represents multiple renewable technologies, said some storage technologies have the proven ability to deliver 100MW in as little as six to 18 months.

She says the South African Wind Energy Association (Sawea) “knows that current operating wind farms could add 500MW immediately to the national grid”. The only reason that they aren’t doing this is because of artificial limits, she said.

Dean said that a significant tranche of solar photovoltaics (PV)will allow additional energy to go to pump storage to serve evening peak usage.

Cape Town’s acting executive mayor Ian Neilson said the city would ask the court for an emergency hearing because of the load-shedding crisis.

“The City of Cape Town intends seeking permission from the Judge President of the Gauteng high court for an expedited hearing on its energy case asking the minister of energy and Nersa [National Energy Regulator of South Africa] to allow it to buy energy from IPPs, Neilson said. The original hearing date is scheduled for May 2020.

“The city’s legal team is liaising with the legal teams of the other parties to the matter with a view to approaching the Judge President with mutually agreeable dates for an earlier hearing.”

That court case might force Mantashe and the rest of government to do what it should have started doing nearly a decade ago.

If the state continues to dither, our future will stay hostage to narrow interests and a coal power industry that is killing people and driving the climate crisis. Down that path lies bankruptcy and darkness.

13 December 2019

Mail & Guardian