Solving the Climate Crisis Means Tackling What We Eat.

As the latest United Nations climate change conference wrapped up in Katowice, Poland earlier this month, policy makers barely kept the Paris Accord alive. Yet the 11th-hour agreement they reached won’t be enough to face of the sobering reality of climate change.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded that avoiding catastrophic climate change can only succeed if governments take immediate, ambitious action across all sectors. That means a rapid shift to renewable energy and away from fossil fuels. But even that won’t be sufficient.

A growing body of research finds that another necessary action is for high-consuming countries to reduce meat and dairy consumption and move toward plant-forward diets and food systems. If current trends continue, food production will nearly exhaust the global carbon budget for all sectors — including fossil fuels — by 2050.

So while the world is rightly focused on keeping fossil fuels in the ground, we also need to alter our food systems. That can start with cutting subsidies to the most climate-intensive segments, like meat and dairy, and then pursuing policies that dramatically elevate plant-friendly diets, local farms and organic foods.

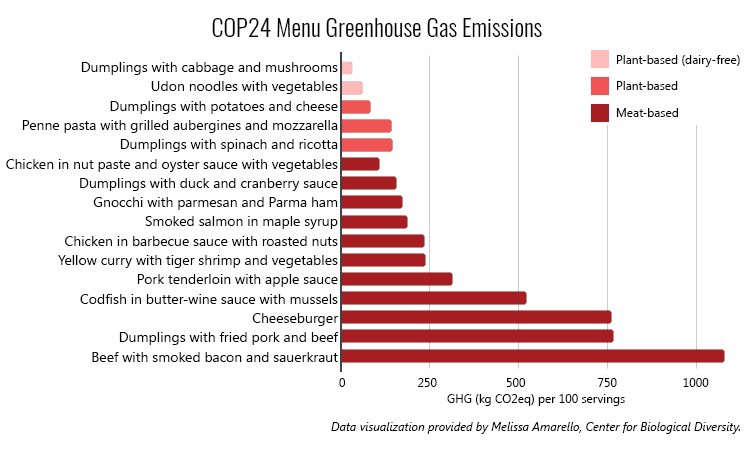

But judging by the carbon-intensive food that was served at the Poland climate conference, it’s clear there’s a long way to go.

An analysis released by our organizations, the Center for Biological Diversity and Brighter Green, along with Farm Forward, found that if everyone at COP24 ate the meat options dominating the menu, it would generate as many greenhouse gases as burning 500,000 gallons of gasoline. That’s equivalent to the emissions attributed to 3,000 people flying from New York to Katowice.

In addition to higher emissions, producing the meat-based dishes for the conference required on average seven times more land and nearly twice as much water as the plant-based dishes do.

This is, of course, about more than what was eaten at the two-week conference.

When it comes to addressing the role of food and animal agriculture in warming the global climate, the silence has been deafening. It’s time for that to end.

Policy makers claim that what people eat is a personal decision, not a political one. We are led to believe that what we eat, grow, and produce is determined by consumer demand as opposed to artificial price supports that encourage farmers and agribusinesses to produce more and more of fewer and fewer commodities to justify sunken costs.

But the truth is that subsidies affect what crops are planted by corporate agribusinesses as well as the market price of those crops. Tax breaks, lobbying by large agricultural producers, and international trade accords favor consolidation and globalization over small farmers. Local ownership and food security are supplanted by cash crops and the reckless extraction of natural resources by multinational corporations.

All of this in turn influences what foods are available and affordable. Meanwhile policies like national dietary guidelines inform nutrition education, large-scale food service and procurement, and how people think about their food choices.

Government policymakers have spent too long kicking the climate ball down the road. In the next two decades, as the effects of climate change grow worse, it’s likely that people will grow angrier and more desperate, and governmental policies more draconian, less measured and more reactive. But that doesn’t have to be the case.

By supporting locally-grown foods, replenished ecosystems and plant-forward diets, we can replace corporate monocultures with a decentralized, organic network that is likely to be more adaptable to the inevitable economic shocks, social breakdown, and climate disasters that await us.

And respecting international agreements like the Paris Accord, however imperfect, can make a difference. For example, the Montreal Protocolsuccessfully closed the hole in the ozone layer. Encouraging innovation on a large scale through government investment and policy levers can accelerate technological change and widespread adoption. This is exactly what we need now.

We can avoid the worst impacts of climate change, and do so in a way that supports the health of people, communities, and the natural world. But it will only happen if world governments bring the need to reduce meat and dairy consumption and production to the climate table.

Stephanie Feldstein is the population and sustainability director at the Center for Biological Diversity, which advocates for sustainable diets and food systems to address the impact of industrial livestock production on wildlife and the environment.

Mia MacDonald is executive director of New York-based action tank Brighter Green, which works at the intersection of environment, animal and global sustainability, including in China on food systems and factory farming.

28 December 2018