The Retreat of Exxon and the Oil Majors Won’t Stop Fossil Fuel.

National oil champions are likely to fill the gap left by private-sector players—meaning emissions won't shrink as fast as the supermajors.

When Exxon Mobil Corp. decided to get out of a big oil field in Iraq, the government took on the unusual role of salesman. Iraqi officials pitched West Qurna-1 to likely buyers from among Exxon’s supermajor peers, including arch-rival Chevron Corp. There weren’t any takers.

That left Iraq with narrowed options: sell to one of China’s state-backed oil majors, or else buy back Exxon’s stake itself. The sale process remains unresolved but either outcome would stand as a powerful indicator of what’s become of the global oil market. With supermajors from the U.S. and Europe in retreat around the world, national oil champions are set to fill the void.

The supermajors — a group that, in addition to Exxon and Chevron, includes BP Plc, Royal Dutch Shell Plc, TotalEnergies SE, and Eni SpA — are shrinking even while fossil-fuel demand holds strong. These companies are under growing pressure to pay down debt while cutting greenhouse gas and, for some, transitioning to renewable energy. Recent weeks saw Exxon and Chevron rebuked by their own shareholders over climate concerns, while Shell lost a lawsuit in the Hague over the pace of its shift away from oil and gas.

Photographer: Peter Boer/Bloomberg

National oil companies, or NOCs, are largely shielded from those pressures. When the owners are governments, not shareholders, there aren’t dissident board members like those now sitting inside Exxon. That means state oil producers like those who populate OPEC+ can be the buyers of last resort for fossil-fuel projects cast off by the shrinking supermajors.

State companies can also gobble market share by simply producing oil that their private-sector rivals won’t. Saudi Aramco and Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. are spending billions to boost their respective output capacities by a million barrels per day each, and Qatar Petroleum is spending more than $30 billion to increase its liquefied natural gas exports by more than 50%. (Aramco and Abu Dhabi National Oil declined to comment.)

Taken together, NOCs make up just over half of today’s worldwide oil supply. By 2050, Rystad Energy sees that share growing to 65%.

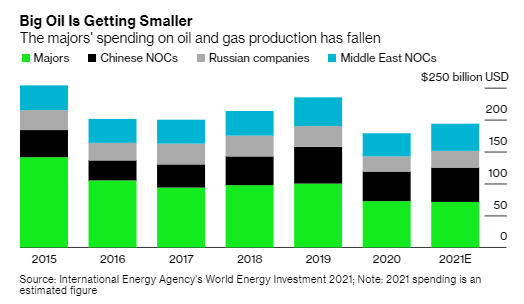

Source: International Energy Agency's World Energy Investment 2021; Note: 2021 spending is an estimated figure

It’s an unmistakable trend that’s drawing heightened attention to some of the largest and most secretive entities in the world. Many government leaders are seeking to lower planet-warming emissions, with nine of the 10 biggest economies staked to net-zero goals. At the same time, these opaque government-sponsored oil producers — insulated in most cases from both investors and environmentalists, and under little obligation to disclose climate data — are taking over the job of filling the millions of barrels consumed each day.

“We hear government officials and NOC officials say, ‘We look at the divestment of international oil companies from some projects as an opportunity for us to grow,’” said Patrick Heller, an adviser at the Natural Resource Governance Institute. “And I do think that’s potentially really risky.”

Some observers worry that campaigns by activists to have oil majors divest from fossil fuels could end up accelerating a shift to government owners who operate with less transparency and, occasionally, worse environmental records. Jason Bordoff, director of the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, argued in a recent essay that such efforts could result in “unintended consequences” without the necessary drop in demand.

For all the focus on companies like Exxon and Shell, the majors recently accounted for only 15% of the world’s supply of oil, according to the International Energy Agency. Some of them are set to see their production drop, too, in part due to selling off chunks of their existing businesses.

BP has spent the past two years pursuing divestment deals partly to help meet its net-zero goal, and next it plans to sell a stake in an Omani gas block to Thailand’s national energy firm for $2.6 billion. Shell, with its own pledge to zero-out emissions, recently said it would hand back leases to the Tunisian government instead of producing more oil from them. Such deals reach beyond oil and gas extraction: Mexico’s Pemex is set to buy a Texas refinery from Shell. (Pemex declined to comment.)

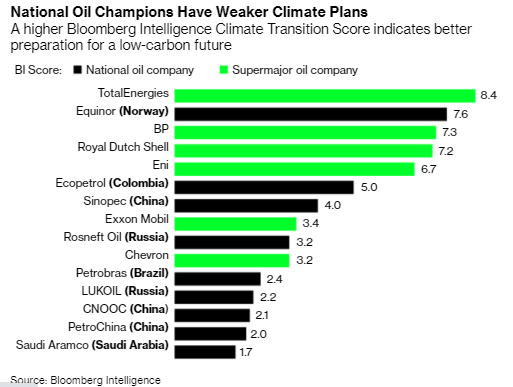

While state-sponsored oil companies vary greatly — from Norway’s climate-conscious Equinor to Russia’s Gazprom, a top three emitter for decades — overall NOCs make an outsized contribution to global emissions. Consider methane, a greenhouse gas that’s far more potent than carbon dioxide in the short term. Countries where state-owned entities dominate energy supply make up three-quarters of all methane emissions from oil and gas, according to the IEA. The vast majority of those methane emissions are attributable to just 15 countries, including Russia, Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

Pressure driving supermajors to shrink isn’t coming solely from climate activists. The IEA drew widespread attention last month when it released its first report laying out a roadmap for a global net-zero economy by 2050. In that scenario, demand for fossil fuels plummets and investment in new oil and gas fields needs to stop. Methane emissions from fossil fuel, meanwhile, would fall 75% by 2030.

In the near-term, the majors have “ample spare capacity,” Bordoff said in an email interview. “But if investment by the majors remains depressed and oil demand continues on its current trajectory, markets will tighten.” As oil prices rise, he sees state-owned or smaller, private players stepping in to fill the gap. “A shift in production to major nationally owned companies — such as in Latin America or the Gulf or Russia — carries geopolitical supply risks,” Bordoff said, “while smaller independents have often demonstrated poorer safety and environmental practices.”

Divestments and reduced spending on exploration means oil majors will simply run out of proved reserves — the quantity of hydrocarbons that they can produce — within 15 years, Rystad said in a recent report, “unless the group makes more commercial discoveries, and fast.”

Even Exxon, which hasn’t set a net-zero target, has severely curtailed its ambitious growth plans to save money and reduce debt. The company is keeping production at the lowest level in two decades through 2025, a drop of 25% compared to pre-pandemic estimates. Exxon's asset sales are “financial transactions, not an effort to reduce emissions from our portfolio,” the company said in a statement. “Our business plans call for reduced emissions intensity, which emphasizes improved operational efficiencies and emissions performance, rather than the divestment of individual assets.”.

Chevron has also backed away from new megaprojects in favor of more flexible U.S. shale. Both companies forecast flat output this year compared to last. BP will cut its oil and gas production by 40% by the end of this decade, while Shell sees a gradual decline in oil output of around 1% to 2% each year.

As a group, the majors are holding spending at 2% lower than last year, the IEA reported last week, despite overall capital expenditures on exploration and production rising 8% in 2021. Spending on new oil and gas fields “has traditionally been well above the levels from their peers in the Middle East, Russia and China,” the IEA said. “This is no longer the case.”

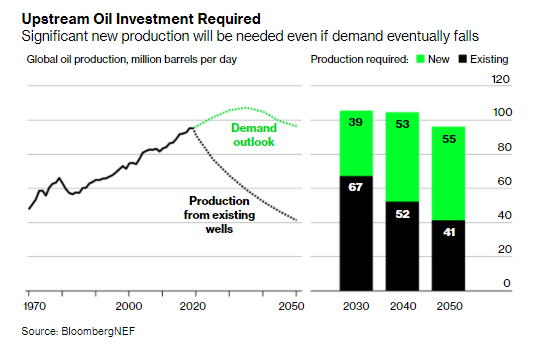

But global demand isn’t falling as rapidly, at least according to current projections. In fact, it’s expected to rise over the next 15 years based on recent estimates from clean-energy researchers at BloombergNEF. That leaves about 55 million barrels of oil a day of new supply needed by 2050, BloombergNEF says, equivalent to global demand in the middle of the 1980s.

State-owned oil companies see this as an opportunity. “A lot of oil and gas host governments and NOCs believe that the industry is underinvesting in exploration and production, and some believe they can step up and fill the gap,” said Ben Cahill, a senior fellow in the Energy Security and Climate Change Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Not all will be able to do so. Cahill said companies like Pemex, Venezuela’s PDVSA and Algeria’s Sonatrach will struggle just to maintain their output. But that leaves giants like Aramco, Russia’s Rosneft and Qatar Petroleum in a position to double down on their core business.

Iraq’s oil ministry said in a statement it’s committed to attracting new investments with international oil companies. This year Iraq has been discussing a $7 billion energy deal with Total, for example, even as Exxon has sought to shed its stake in an oil field. “Everyone knows that many international companies have changed their strategies,” said Asim Jihad, an oil ministry spokesman. “Iraq respects the will of the companies operating in Iraq.”

t’s hard to glean a complete picture of what that will mean for emissions, in large part because many state-owned companies don’t disclose greenhouse-gas data. Aramco recently revamped its disclosures and still doesn’t report data from join ventures or the emissions from customers burning its fuels. Overall, disclosure from state-owned oil companies are highly variable and lack the transparency of the majors.

But what little is known indicates there’s low-hanging fruit on greenhouse gas from NOCs. In some cases it would cost nothing for petrostates to slash methane emissions, according to a previous IEA report.

“NOCs are sort of the biggest keys when it comes to looking at country-level emissions,” said Ratnika Prasad, director of energy strategy at the Environmental Defense Fund, which recently commissioned a report by Carbon Limits on methane emissions by state-owned oil companies. “It’s easy to see how taking action on NOC emissions, especially methane, will yield pretty quick and more effective climate results.”

Pressuring government-run entities to take action introduces new, daunting hurdles. After years of campaigning, there’s a playbook of sorts for forcing change at the Western supermajors. Activist groups such as Follow This and As You Sow encourage climate-conscious citizens to buy stock in publicly traded companies like Exxon or Shell. Then shareholder activists push climate-friendly proxy measures during annual shareholder meetings.

Strategic pivots by Shell and BP toward low-carbon fuels came after years of intensifying shareholder pressure, and the same process appears to be playing out inside Exxon right now. The Texas oil giant lost an unprecedented battle with an activist investor Engine No. 1 at its annual meeting this year. With just 0.02% of Exxon’s shares, the previously unknown group won backing from large institutional investors and placed three of its own candidates on Exxon’s board.

State-owned entities lack an equivalent mechanism, unless a significant portion of their shares is listed on a stock exchange. Any drive to lower emissions is tied to the ambitions of the countries that own them. “NOCs are at the core of economic life in a lot of oil producing countries,” said Heller. “The health of the NOC is in some cases seen as synonymous with the health of the economy overall. So that does contribute to status-quo thinking.”

There’s some cause for optimism. Countries with the most prolific state-backed oil companies have signed on to the Paris Agreement, with some taking their commitment a step further and participating in voluntary coalitions aimed at reducing emissions. The Oil and Gas Climate Initiative counts five national oil companies, including Aramco and China National Petroleum Corp., among its members. That organization requires a target to reduce the average methane emissions per barrel of oil produced by 2025, although this doesn’t ensure that absolute emissions will fall.

To some degree, this is a phenomenon that Exxon has been warning against for years. As BP and Shell have sold off assets in a pivot to renewables, Exxon has said such moves only work to move production — and emissions — elsewhere. Exxon CEO Darren Woods drew criticism from climate activists last year for labeling rivals’ asset sales to lower emissions nothing more than a “beauty competition.” His wider point underscores the long path ahead for the world as it grapples with climate change.

“This is not a company challenge, this is a global challenge,” Woods said in March 2020. “This idea of moving things in and out of the portfolio from one company to the other actually isn't getting us any closer to a solution.”

But Mark van Baal, founder of Follow This, said that by pressuring the majors it’s still possible to drive an overall reduction in emissions—even without directly challenging the NOCs. State-owned entities will follow if majors push ahead on investment in renewable energy, he said, lowering the costs for everyone. “We need the most innovative oil and gas companies to change and put their full weight behind renewables to speed up the energy transition,” van Baal said. “Others will follow.”

— With assistance by Dave Merril, Gerson Freitas Jr, Eric Roston, Khalid Al Ansary, and Anthony Di Paola

9 June 2021

Bloomberg Green