Stop CO2 emissions bouncing back after Covid plunge, says IEA.

Governments are not doing enough to prevent rapid rebound, says agency’s report.

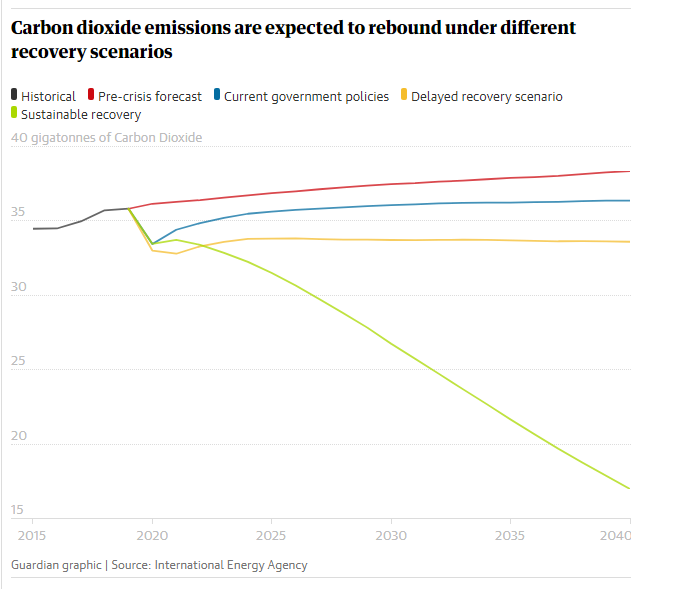

The coronavirus pandemic is expected to cause a record 7% decline in global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions in 2020, but governments are not doing enough to prevent a rapid rebound, according to an influential report.

Carbon dioxide emissions from energy use are expected to fall to 33.4 gigatonnes in 2020, the lowest level since 2011 and the biggest year on year fall since 1900 when records began, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said in its annual world energy outlook.

The pandemic has prompted a large drop in global economic activity, with energy demand expected to fall by 5% in 2020, the largest decline in the past century barring the world wars and the 1929 Great Depression, said the global energy watchdog. Carbon emissions are set to fall faster as zero-carbon renewable energy sources continue to grow, while the use of fossil fuel sources drops steeply.

The pandemic has proved to be a catalyst for a move away from coal in particular towards solar power, said Fatih Birol, the IEA executive director. Coal, which tends to be among the most polluting fossil fuels, will soon account for only a fifth of global energy use, the lowest level since the Industrial Revolution.

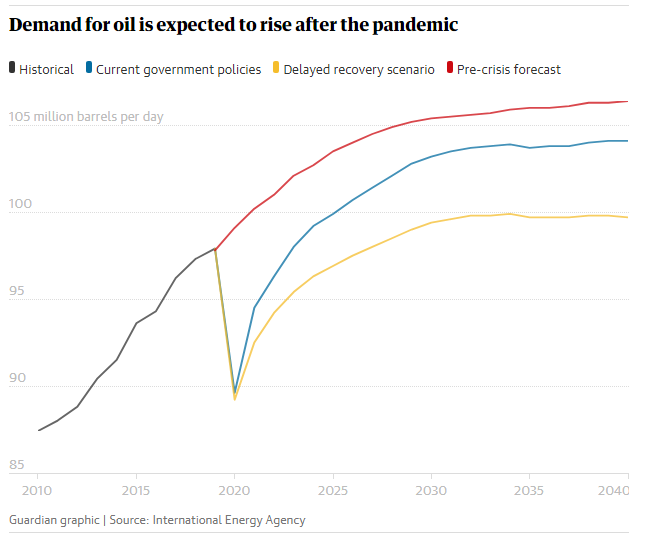

Oil demand growth is also expected to peter out in the next decade, but Birol warned against complacency that the pandemic would help to reduce oil demand or broader carbon emissions permanently. He said he did not see clear signs of a peak in oil demand or a rapid decline based on current policy positions.

Under one scenario modelled by the IEA, based on governments’ current policies, carbon dioxide emissions will rebound in 2021, exceed 2019 levels in 2027 and rise to 36 gigatonnes by 2030. Under a much more optimistic “sustainable development” scenario, global emissions could peak in 2019 but Birol warned that would require a rapid change in global energy policy.

“The world is far from doing enough to put [emissions] into a structural decline,” he said. “We expect that global emissions will bounce back with the rebound of the economy if no large shifts in government policies take place.

“When I look at the scale of the challenge I believe governments have a historic task today to facilitate and in some cases directly invest in clean energy infrastructure.”

Birol said the Covid crisis would “leave scars for many years to come”, particularly for the world’s poorest people, echoing warnings from the World Bank. Rising poverty levels may have made basic electricity services unaffordable for more than 110 million people, reversing several years of progress in access to electricity, the IEA said.

Global annual investment in clean energy needs to increase from $300bn (£230bn) to $1.6tn by 2030 – equivalent to total energy investment in 2020 – if it is to have any hope of tackling the climate crisis, Birol said.

The rapid rise of solar power and wind power, a key focus for the UK government, meant renewable energy sources will account for an increasing proportion of the world’s new energy needs. The IEA forecasted that solar power will increase by an average of 13% a year between 2020 and 2030.

“Solar is the new king of global electricity markets,” Birol said, with growth across the world and cheap financing making solar power in some cases among the cheapest sources of electricity in history.

Yet while the pandemic may have accelerated some improvements in the energy system, consumers in richer countries becoming more environmentally conscious is not enough, the IEA said.

“The Londoners or Parisians or New Yorkers eating less pineapple from Costa Rica may have an impact, but the main impact is tens of millions of people in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Congo will buy their first refrigerators and air conditioners,” Birol said.

He also highlighted an important blind spot in the global climate debate about the need to improve existing energy infrastructure, as well as introduce new technology. Using the energy infrastructure currently in existence as before would lock in global temperature rises of 1.65°C, missing the 1.5°C goal of the 2015 Paris agreement, the IEA found.

13 October 2020

The Guardian