Polluted air killing half a million babies a year across globe.

State of Global Air report says indoor air quality causing two-thirds of the deaths and affecting health in the womb.

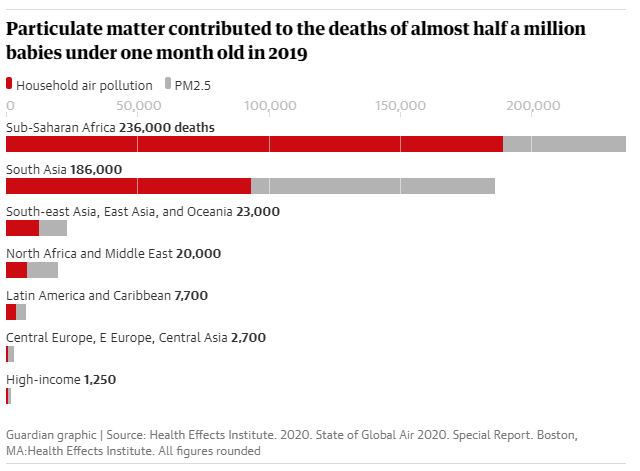

Air pollution last year caused the premature death of nearly half a million babies in their first month of life, with most of the infants being in the developing world, data shows.

Exposure to airborne pollutants is harmful also for babies in the womb. It can cause a premature birth or low birth weight. Both of these factors are associated with higher infant mortality.

Nearly two-thirds of the 500,000 deaths of infants documented were associated with indoor air pollution, particularly arising from solid fuels such as charcoal, wood, and animal dung for cooking.

The discovery is reported in the State of Global Air 2020 report, which examined data on deaths around the world alongside a growing body of research that links air pollution with health problems.

Medical experts have warned for years of the impacts of dirty air on older people and on those with health conditions, but are only beginning to understand the deadly toll on babies in the womb.

Katherine Walker, principal scientist at the Health Effects Institute, which published the report, said: “We don’t totally understand what the mechanisms are at this stage, but there is something going on that is causing reductions in baby growth and ultimately birth weight. There is an epidemiological link, shown across multiple countries in multiple studies.”

Babies born with a low birth weight are more susceptible to childhood infections and pneumonia. The lungs of pre-term babies can also not be fully developed.

“They are born into a high pollution environment, and are more susceptible than children who went to term,” said Dan Greenbaum, president of the Health Effects Institute in the US.

Beate Ritz, professor of epidemiology at UCLA, (University of California, Los Angeles), who was not involved with the study, said the indoor air pollution in cities across India, south-east Asia and Africa was comparable to that of Victorian London.

“This is not the air pollution we see in modern cities [in the rich world] but that which we had 150 years ago in London and other places, where there were coal fires indoors. Indoor air pollution has not been at the forefront for policymakers, but it should be,” Ritz said.

She pointed out that the harm to children went beyond the deaths; reducing air pollution would also lessen harm to survivors. “There is also damage to the brain and other organs from this pollution, so just surviving is not enough – we need to reduce air pollution because of the impact on all these organs too,” she said.

Some of these effects are likely to have existed, unnoticed, for centuries, as people have long cooked upon fires in enclosed spaces, an activity that causes particulate matter to be breathed in, particularly by women and children, who spend more time in the home.

However, the problem is now compounded by the population density of many developing cities and by outdoor air pollution from vehicles and industry. These factors mean there is now no escape from dirty air, from morning to night, for hundreds of millions of people.

The report concentrates on data from 2019, so does not include the impacts of the lockdown policies around the world in 2020. The authors said the Covid-19 pandemic would have had an impact on air quality and deaths from air pollution, but these effects were not yet clear.

Greenbaum said the likelihood of any long-term beneficial impact to health from the temporary reductions in air pollution because of lockdowns was small, but that the sudden clearing of pollution from traffic and industry had changed many people’s perception of air quality.

“People all of a sudden realised what it is like to have beautiful blue skies on a regular basis. Even if it did not last it showed what was possible,” Greenbaum said.

Some studies have suggested that people exposed to air pollution could have a higher risk of death from Covid-19, but these are early findings. Greenbaum said more work was needed to establish what difference was made by exposure to air pollution.

The scientists said there had been little sign of improvement in air pollution over the past 10 years, despite increased warnings over the risks from dirty air in the past five years.

At least 6.7 million deaths globally in 2019 were from long-term exposure to air pollution, a factor raising the risk of stroke, heart attack, diabetes, lung cancer and other chronic lung diseases. Air pollution is now the fourth highest cause of death globally, just below smoking and poor diet.

The State of Global Air Report 2020 is published by the Health Effects Institute, which is an independent nonprofit research organisation funded by the US Environmental Protection Agency and others.

21 October 2020

The Guardian