New research links Asia's air pollution with heavy economic impacts, thousands of premature deaths.

BANGKOK: For Bangkok’s “Spiderman Team”, dangling on ropes and rappelling down the city’s tallest buildings is just one of the risky parts of their job.

High above the choked streets, on many days throughout the year the greatest adversary for the glass window cleaners is the very air they breathe. In the Thai capital, the situation is getting worse by the year.

The irony is that for the cleaning company, the persistence of air pollution actually means their services are needed more often. But there is concern for those braving the elements.

“Of course, it’s getting worse. For the ‘spider men’, I am worried about them because they are working on the high-rise facade and the air up there isn’t good during the time that air pollution rises,” said the company’s owner Suchart Owatwunasakul.

Having to shield their workers from the impacts of damaging air pollution is an economic impost on the company - Owat Pro & Quick - that hires 30 expert window cleaners and a total of 2000 staff.

“Our window cleaning team has life insurance, health check-ups, health insurance with accident insurance, as well as social welfare. When the air pollution gets bad, we give out and instruct our workers to wear 3M masks,” he said.

The economic and health effects of prolonged ar pollution in major Asia cities is an area of growing concern, and researchers appear to have made headway in quantifying the economic cost and premature deaths linked to bad air.

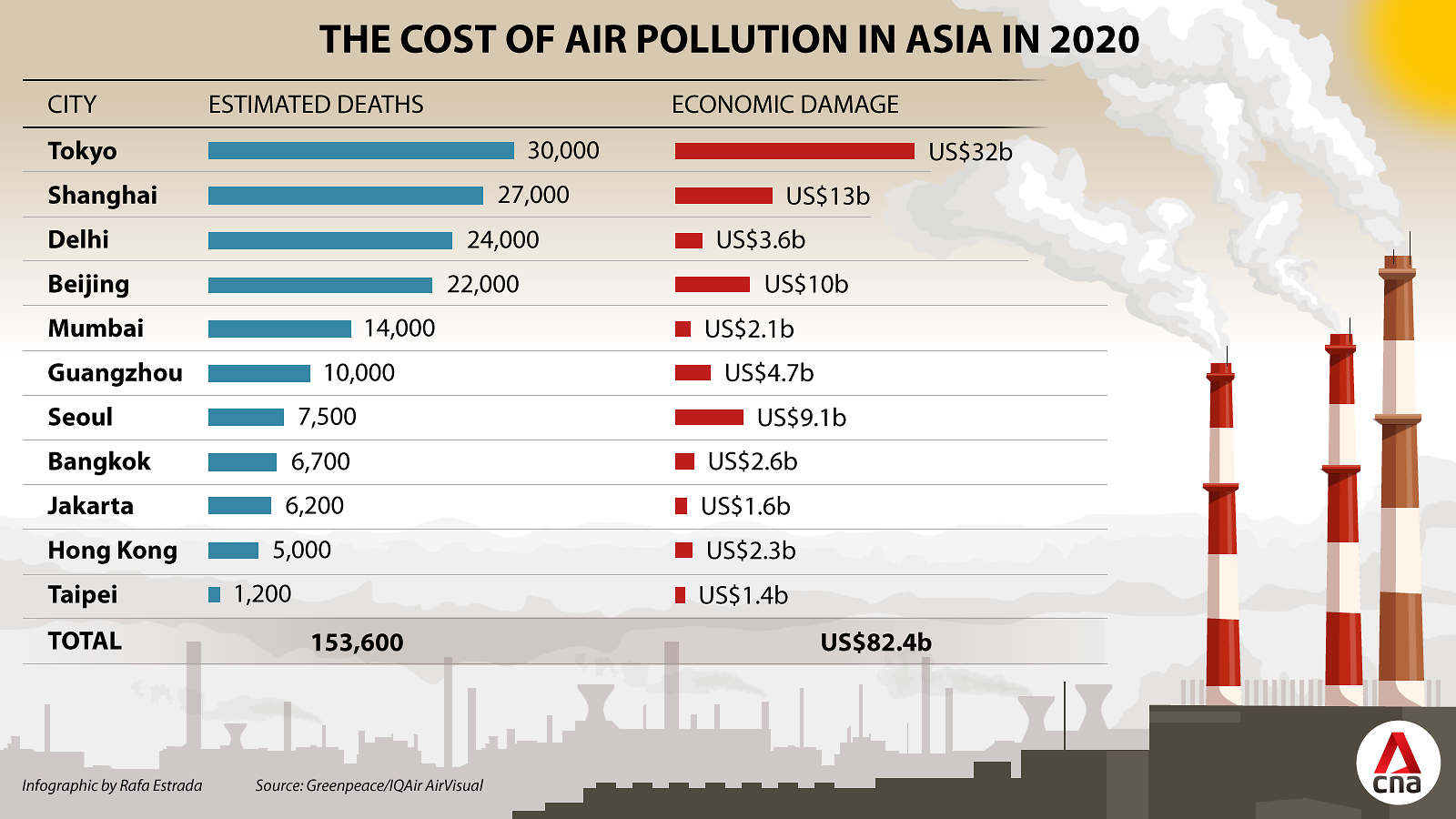

According to a new tool that tracks the impacts of degraded air quality in real time, air pollution has contributed to a combined estimated 153,600 premature deaths and US$82.4 billion in economic loss up to Jun 30 this year in just 11 major Asian cities.

The tool, developed by Greenpeace and IQAir AirVisual - an air quality information platform - analyses world cities based on live air quality data, scientific risk models and local health and population data.

It is powered by analysis by the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) that aimed to quantify the global economic burden caused by air pollution from fossil fuels. It uses advanced metrics to link specific health impacts to pollution, analysing the extent of air pollution over the previous 365 days.

“Quantifying such economic cost makes the threat of air pollution more tangible and allows us to bridge the disconnect in understanding that the air we breathe everyday has far reaching effects to our bodies and to our environment,” said CREA’s Southeast Asia analyst, Isabella Suarez.

“This is important because some major sources of air pollution - like fossil fuels - are still considered necessary economic drivers when they actually have an immense, but hidden burden that greatly outweighs their economic returns,” she said.

“As countries are pursuing stimulus and recovery from COVID-19, it is increasingly important to make these costs part of the equation so we prioritise solutions that are good for both citizens' health and the economy.”

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has also taken strides to measure the true impact of air pollution on economies and public health. It estimates that Southeast Asia has an annual burden of 2.4 million premature deaths from air pollution.

The use of satellite information, remote sensing of pollutants and the integration of data in recent years has allowed countries to start to better understand the problem, said Dr Poonam Khetrapal Singh, the regional director of WHO South-East Asia.

“This provides important information on the factors that may modify the effect of air pollution on mortality and morbidity such as co-morbidities, the contribution of air pollution to existing disease burdens in a country that air pollution exacerbates, the impact on vulnerable groups in society and the cost to society of not taking action,” Dr Singh told CNA.

He said that while there are some improvements being seen, especially around household pollutants, regional governments are still in the early years of acknowledging the extent of the issue and taking the right actions to deal with it.

“In Southeast Asia, air pollution in cities continues to be worrisome,” he said. “Data shows Southeast Asia to have some of the largest impact of the combined impact of ambient air pollution and household air pollution from the use of burning biomass to meet household energy needs.”

The worse the air, the higher the risk of death and the more real world mortalities, based on official city data, are attributed to the effects of pollution. In Asia, the problem is significant.

DEADLY CONSEQUENCES

Despite strict and long-lasting social lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw air pollution decrease for several months in most regions, deaths from bad air have been significant in large Asian metropolises, far outnumbering those who have died from the coronavirus in the selected cities.

In Bangkok, the CREA data approximates that air pollution contributed to 6,700 deaths this year; by contrast, Thailand has recorded only 58 deaths attributed to COVID-19. By improving air quality to WHO accepted standards, the average Thai could increase their life expectancy by 2.1 years, the Air Quality Life Index says.

The number is 6,200 deaths in Jakarta, which is on track to be higher than previous annual estimates. Just last year Greenpeace Indonesia had estimated that about 7,400 Jakartans die early every year due to high levels of PM2.5 - tiny atmospheric particulate matter mostly produced by vehicles, refineries and other heavy industry.

“Unlike other cities around the world, Bangkok and Jakarta saw little improvement in their air quality during their COVID-19 lockdowns despite major disruptions in urban activity. This indicates that there are other significant sources of pollution in each of the cities that were still operating business as usual,” Suarez said.

Jakarta was ranked the 11th worst capital city in terms of annual air pollution in 2018, based on global recordings by IQAir, while Bangkok was ranked the 24th worst.

“Jakarta overtook Beijing on the list (of polluted capital cities) in 2018 and was the most polluted in Southeast Asia in 2019. As they remain heavily reliant - or even increase reliance - on fossil fuels for transport, industries, and power, it is likely that air quality will worsen,” she added.

WEAKENED HEALTH IN THE LONG RUN

Prolonged exposure to harmful air pollution is known to weaken resistance to respiratory diseases and can heighten the risks of lung cancer and heart disease.

“PM2.5 isn’t a pandemic, but it has long-term impacts on people’s health, weakening people’s health in the long run,” Dr Supat Wangwongwatana from the Faculty of Public Health at Thammasat University in Bangkok and the former director-general of Thailand's Pollution Control Department told CNA.

Overall, CREA’s research found that 4.5 million people globally died in 2018 due to exposure to air pollution from fossil fuels, combined with an economic cost of US$2.9 trillion.

It estimates that 30,000 deaths in Tokyo this year up to Jun 30 are linked to air pollution, on top of an economic cost of US$32 billion. A 2015 Global Burden of Diseases Study study had previously estimated that 60,000 premature deaths were caused by air pollution in Japan every year.

Major Chinese cities - Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou - have also been hit hard for a combined 59,000 linked deaths and US$27.7 billion in losses. Analysis found that PM2.5 and NO2 levels, among other pollutants, in many Chinese cities have already exceeded 2019 levels, as the economy rebounds from sharp drops in industrial activity in the peak of the pandemic period.

And despite India recording its first year-on-year drop in national carbon emissions for nearly four decades - and witnessing rare blue skies during the pandemic lockdown period - New Delhi has suffered an estimated 34,000 air pollution-related deaths in 2020 and a US$3.6 billion hit to its economy.

The economic impacts quantified by CREA manifest in different ways, all determined by existing studies, which demonstrate that the rise in incidence of chronic and acute illnesses can put major strains on health systems and reduce system-wide productivity.

If it is known that a sustained rise in air pollution increases the risk of death from lung cancer by 25 per cent, for example, the analysis will deem that the same proportion of the deaths from that disease experienced in any particular city would have been prevented if the air was clean.

Working age mortalities can negatively affect labour markets. For older people, the loss of their spending power is deemed a cost to the economy. Children suffering from asthma attacks have impacts on learning potential and for their carers who need to spend more time at home rather than work. Likewise, adults with acute health problems may be unable to attend work more often.

Impacts on gross domestic product (GDP) from air pollution are also calculated to be more pronounced in cities with higher levels of income. It means more advanced cities like Tokyo can experience greater strains on their economy and health system, despite air being more polluted in other cities.

CIVILIAN ACTION

Private citizens and organisations have resorted to legal mechanisms in a bid to fast track air quality improvements.

The Thai Chamber of Commerce, which represents local businesses and companies, late last year submitted a proposal for a draft clean air bill. It cited the ongoing adverse impacts of air pollution on the economy, including small business and tourism.

The group argued that current laws do not adequately address the issue and penalise offenders.

In July the chamber submitted a list of 12,000 names endorsing the draft Air Management Administration Act, which would include setting up an oversight committee headed by the prime minister, clear air pollution standards and better quality monitoring systems.

“The public has a right to access clean air,” the chamber’s chairman Kalin Sarasin wrote in a Facebook post then. “Thailand must reform its management system to have clean air and ensure that the system is up to standard.”

In Indonesia’s capital, an air pollution lawsuit filed by citizens against the government is underway. The defendants, including the president, environment minister and Jakarta governor, are blamed for not taking sufficient action to reduce pollution levels and safeguard the public.

“To Jakartans, let’s not cease to be critical and demand our rights to clean and healthy air, as it is part of the right to a good and healthy environment,” the coalition of Jakarta residents behind the lawsuit said in a statement earlier.

Environmental groups are urging governments to make investing in clean transport and renewable energy key planks in their post COVID-19 strategies, citing the clear benefits to public health.

Yet, the Indonesian government continues to pursue coal-powered energy - it plans to almost double the installed capacity of its coal plants over the next decade - while emissions from the burning of peatlands shroud many parts of the country in a toxic haze on a near-annual basis.

“Up until now, the government is making a little effort to promote renewable energy shifts compared to the development of new coal power plants,” said Satrio Swandiko Prillianto, Greenpeace Indonesia’s renewable energy campaigner.

However, while the regional renewable energy sector has been disrupted by the financial and supply challenges of the pandemic, the long-term prospects for a shift to wind and solar sources remain on track in many countries.

Asia is already the world leader for renewable sector growth - up 7.6 per cent of supply in 2019 and accounting for 54 per cent of new global additions in 2019 - according to an annual report by the International Renewable Energy Agency.

“In addition to clean energy for the grid, improving air quality involves investing in low-carbon and energy efficiency for other sectors like buildings, transport, and industry,” Suarez said.

“It really comes down to implementation though; policies need to be designed to ensure compliance, move us away from heavily-polluting sources, and make the air quality improvement process iterative.”

Delve deeper, read our special coverage on climate change here: cna.asia/climatechange

4 August 2020

ASIA CNA