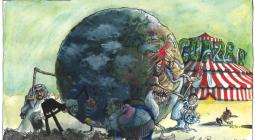

Global carbon emissions from fossil fuels to hit record high

Global carbon emissions from fossil fuels reached record levels again in 2023, as experts warned that the projected rate of warming had not improved over the past two years.

The world is on track to have burned more coal, oil and gas in 2023 than it did in 2022, according to a report by the Global Carbon Project, pumping 1.1% more planet-heating carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at a time when emissions must plummet to stop extreme weather from growing more violent.

The finding comes as world leaders meet in Dubai for the fraught Cop28 climate summit. In a separate report published on Tuesday, Climate Action Tracker (CAT) raised its projections slightly for future warming above the estimates it made at a conference in Glasgow two years ago.

“Two years after Glasgow, our report is virtually the same,” said Claire Stockwell, an analyst at Climate Analytics and lead author of the CAT report. “You would think the extreme events around the world would be sparking action but governments appear oblivious, somehow thinking treading water will deal with the flood of impacts.”

As carbon clogs the atmosphere, trapping sunlight and baking the planet, the climate is growing more hostile to human life. The growth in CO2 emissions had slowed substantially over the past decade, the Global Carbon Project found, but the amount emitted each year had continued to rise. It projected that total CO2 emissions in 2023 would reach a record high of 40.9 gigatons.

If the world continued to emit CO2 at that rate, the international team of more than 120 scientists found, it would burn through the remaining carbon budget for a half-chance of keeping global heating to 1.5C (2.7F) above pre-industrial temperatures in just seven years. In 15 years, the scientists estimated, the budget for 1.7C would be gone too.

The researchers reported big regional differences in emissions. They expected fossil fuel emissions to have risen this year in India and China, the biggest and third-biggest polluters, and to have fallen in the US and the EU, the two biggest historical polluters. The average of the rest of the world’s emissions was expected to have fallen slightly too.

Emissions from deforestation and other land-use changes were also projected to have fallen slightly, though not by enough for current levels of tree-planting to make up for it, the researchers found.

For the first time, the scientists also teased out the growth in emissions from flights and ships abroad. The two together were expected to have grown 11.9%, driven by soaring emissions from aviation.

Pierre Friedlingstein, a climate scientist at the University of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute and lead author of the study, said: “The impacts of climate change are evident all around us but action to reduce carbon emissions from fossil fuels remains painfully slow.

“It now looks inevitable that we will overshoot the 1.5C target of the Paris agreement, and leaders meeting at Cop28 will have to agree rapid cuts in fossil fuel emissions even to keep the 2C target alive.”

On Saturday, more than 117 governments at the summit in Dubai agreed to triple the world’s renewable energy capacity and double the rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030.

Some leaders have also backed efforts to phase out fossil fuels, though only a handful have expressed support for a non-proliferation treaty.

Governments were happy to promote clean energy but had done little to penalise fossil fuels, said Glen Peters, a research director at the climate research institute Cicero, who co-wrote the report.

“It is simply not enough to support clean energy. Policies are also needed to drive fossil fuels out of the energy system,” he added.

The report also found that technology to suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere would have done almost nothing to stop global heating this year. Current levels of technology-based removal – which does not include carbon absorbed by trees – are more than 1m times smaller than current fossil CO2 emissions, the researchers found.

Corinne Le Quéré, a research professor at the University of East Anglia’s School of Environmental Sciences, said: “All countries need to decarbonise their economies faster than they are at present to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.”