Does the UK need new nuclear power to reach its climate goals?

As Boris Johnson eyes a large new nuclear deal as part of his '10-point climate plan', researchers tell Daisy Dunne that such projects could deliver a needed boost to energy supply, but at a high cost.

New nuclear power could be set for a major boost in the UK. The prime minister is reportedly meeting with senior cabinet ministers this month to discuss the role of nuclear in the UK’s future energy supply, and it is expected that new nuclear will feature in his upcoming “10-point plan” for tackling the climate crisis.

On Wednesday evening, Boris Johnson said: “There is no time to waste. That’s why I’ll be setting out my 10-point plan shortly, which will not only create thousands of British jobs but also invigorate our plans to achieve net zero by 2050.”

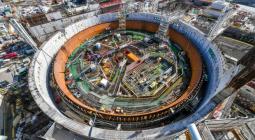

The most likely candidate to get the green light under Mr Johnson’s new plans is Sizewell C, a proposed nuclear power station that would be built on the Suffolk coast. The project’s contractors, EDF Energy, say the station would be an “almost identical replica” of Hinkley Point C, the last large nuclear power station to get the go-ahead in the UK.

The greatest draw of such projects is that they can deliver a “huge source of clean electricity”, Dr Jonathan Marshall, head of analysis at the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit, a non-profit organisation based in the UK, tells The Independent.

“We need an awful lot of electricity,” he says. “Most of our scenarios that project how we’re going to get to net-zero emissions show that electricity use is going to double or treble within the next few decades.”

The demand for electricity in the UK is expected to rocket as people increasingly turn to electric cars in the coming decades. The demand from the industrial sector is also projected to increase as the UK gears towards producing clean hydrogen, which requires large amounts of electricity, says Marshall.

At the same time, the UK must move away from coal and fossil gas in order to meet its goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. Renewables sources of electricity, especially offshore wind, are expected to play the major role in helping the government to transition away from fossil fuels.

But unlike some renewables such as onshore wind and solar projects, large nuclear power stations could deliver a large boost to the electricity supply without taking up lots of land, says Professor Jim Watson, an energy systems and policy researcher at University College London.

“One positive is the sheer volume of low-carbon electricity you get,” he tells The Independent. “Once Hinkley C is built, estimates are that around 7 per cent of electricity would come from that one power station. If you were to build 10 of those, you’re currently at about three-quarters of Britain’s electricity use.”

The UK currently sources about 20 per cent of its electricity from nuclear on an annual basis. This is much lower than neighbouring France, which gets around three-quarters of its electricity from nuclear at present, says Watson.

But there are major costs to consider. One is that new nuclear projects have remained expensive, whereas the cost of renewables such as offshore wind and solar is falling dramatically year on year.

“At the moment, the large reactors are looking very expensive in comparison to other low-carbon technologies,” says Watson. “I think if the nuclear industry and politicians want nuclear to play a role then that’s the challenge they need to address: is it possible to get those costs down?”

Large nuclear projects tend to be costly because they involve complex technology that requires a large amount of upfront investment, Watson says. In addition, past nuclear disasters such as Chernobyl and Fukushima have led to greater regulation of new projects, which, in turn, has driven up costs, he adds.

One way the government might try to reduce the costs of new nuclear is by taking an equity stake in new projects. This would mean “the government or the taxpayer would take more of the risk and that might reduce the financing cost and, therefore, the cost of new nuclear”, says Watson.

Another flaw of large nuclear projects is that they take much longer to come on to the power grid than other types of low-carbon energy.

“At the moment, the timescales of developing new nuclear power are still very long for the large reactors,” says Watson. “So any new stations Boris Johnson might announce from now on are not going to generate electricity until the end of this decade at the earliest.”

Hinkley Point C has been plagued by lengthy delays and rising costs, as have similar projects in France and Finland.

Other European countries do not have plans for new large nuclear projects, says Marshall. And Japan, which suffered the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011, has explicitly said it will meet its net-zero target without pursuing new large nuclear projects.

Another concern is public approval. Big nuclear power projects have always divided opinion in the UK. This year’s UK climate assembly, a first-of-its-kind project that asked the public its opinion on how the country should reach net-zero emissions, came up with a familiar result: 46 per cent of people said they either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the notion that nuclear should be used to reach net zero.

By comparison, 80 per cent of the assembly participants said they strongly agreed that offshore wind should be used to reach net zero, and more than half of participants said the same about solar power.

(Getty Images)

The proposed Sizewell C project has also drawn criticism for its potential environmental costs. The RSPB has warned that the station would cause the destruction of Minsmere, a natural reserve that is home to more 6,000 species, including otters, water voles, marsh harriers and bats.

In response to this criticism, EDF has previously said that Sizewell C would deliver a “net gain for biodiversity”. (This claim is disputed by the RSPB.)

“The government has committed to protect 30 per cent of the UK’s land by 2030 to boost biodiversity, so allowing the destruction of one of the most nature-rich places we already have in the UK would be a crazy decision,” said Beccy Speight, chief executive of the RSPB.

12 November 2020

INDEPENDENT