WHO slashes guideline limits on air pollution from fossil fuels

Level for the most damaging tiny particles is halved, reflecting new evidence of deadly harm

The World Health Organization has cut its recommended limits for air pollution and urged nations to tackle dirty air and save millions of lives.

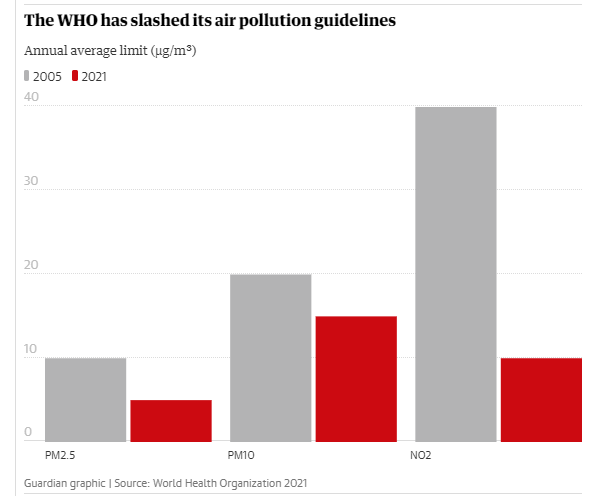

In the first update for 16 years, the guideline limit for the most damaging pollution – tiny particles from burning fossil fuels – has been halved. The new limit for nitrogen dioxide (NO2), mainly produced by diesel engines, is now 75% lower.

The stringent new limits reflect the large body of evidence produced in recent years of the deadly harm caused to people by much lower levels of pollution than previously thought. Air pollution kills at least 7 million people a year, the WHO said, while a recent study estimated 8.7 million early deaths a year from coal, oil and gas burning – 20% of all deaths.

Pollution cuts an average of two years from the lives of the global population, and up to six years in highly polluted nations such as India, making it a bigger killer than smoking, car crashes or HIV/Aids.

Scientists stressed that even the new limits should not be considered safe, as there appears to be no level at which pollutants stop causing damage. They said reducing pollution would boost health even in nations with relatively clean air. A 2019 review concluded that air pollution may be damaging every organ in the body, causing heart and lung disease, diabetes and dementia and reducing intelligence.

Air pollution is the biggest environmental threat to human health and is a public health emergency, according to the WHO, costing trillions of dollars a year. More than 90% of the global population already breathes levels of pollution above the WHO’s 2005 guideline for tiny particles. Cutting air pollution brings huge and cost-effective health benefits and reduces the carbon emissions driving the climate crisis.

“Air pollution is a threat to health in all countries,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the WHO director general. The guidelines are not legally binding but can be used by countries to plan their action. “I urge all countries to put them to use to reduce suffering and save lives,” he said. The WHO said dirty air often affected the most vulnerable people and that clean air should be a “fundamental human right”.

The campaigner Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, whose daughter Ella became the first person to have air pollution cited as an official cause of death, said: “Air pollution stunts children’s health and future. There is no safe level but at least following the WHO’s new guidelines will set us on the path to achieving clean air for all.”

Lwando Maki, a doctor at the Public Health Association of South Africa, said: “I saw the impacts of toxic air pollution every single day in Johannesburg. Updates to air quality standards were long overdue.”

Renewable energy is often cheaper than fossil fuels even without taking the economic burden of air pollution into account, said Avinash Chanchal, of Greenpeace India. “We have all the tools we need to solve the air pollution crisis. At this point, addressing air pollution is a question of political will, not technology.”

Every one of the 100 most populous cities in the world exceeded the new WHO guideline for tiny particle pollution in 2020, according to Greenpeace analysis. This includes Tokyo, Shanghai, New York, Lagos, London and Delhi, with the latter exceeding the limit by 17 times.

Dorota Jarosińska, the WHO’s technical lead for the new guidelines, said: “These are very ambitious public health recommendations and achieving the guideline levels would be the ultimate goal, but all the steps towards it are critical.

“The interim targets [the WHO has also set] are milestones on this continuous march towards getting air quality that is most protective to health. Every step you make towards improving air quality brings health benefits.”

The new guidelines are the product of five years of systematic review by dozens of scientists, considering more than 500 studies and including several rounds of peer review. The guidelines represent the level at which there is already strong evidence for harm to health.

“We feel confident that these are really robust,” said Jarosińska. “But these levels absolutely do not mean we are confident that there is no harm [at even lower levels].”

One of the most harmful pollutants is tiny particulate matter, smaller than 2.5 microns in size (PM2.5), which can pass through the lungs into the bloodstream and affect other organs. The WHO has reduced the guideline for annual average exposure to PM2.5 from 10 to 5 micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m3). The WHO classified these particles as cancer-causing in 2013. For NO2, the WHO has cut the annual average limit from 40 to 10 µg/m3.

Almost 80% of the millions of deaths related to PM2.5 could be avoided if today’s pollution levels were reduced to those in the new guidelines, according to the WHO, compared with a 48% reduction under the 2005 limit. The WHO also said: “Air pollution is most likely a contributing factor to the health burden caused by Covid-19.”

In the UK, the environmental lawyers ClientEarth said legal pollution limits for PM2.5 and NO2 were now four times the WHO guidelines, meaning people are exposed to levels far above that known to be acceptable. NO2 levels are already above UK limits in 75% of urban areas.

“These new guidelines reflect the best available science and the conclusion is irrefutable: air pollution, even at lower levels, seriously endangers people’s health,” said Andrea Lee, of ClientEarth. “This must serve as a wake-up call for the UK government – ministers should be scrambling to act.”

A spokesperson for the UK’s environment ministry said: “We will set ambitious targets on air quality through our environment bill. We will consider the updated WHO guidelines on PM2.5 to inform the development of air quality targets, but we must not underestimate the challenges these would bring, particularly in large cities and for people’s daily lives.” A consultation on the proposed targets is expected in early 2022.

22 September 2021

The Guardian