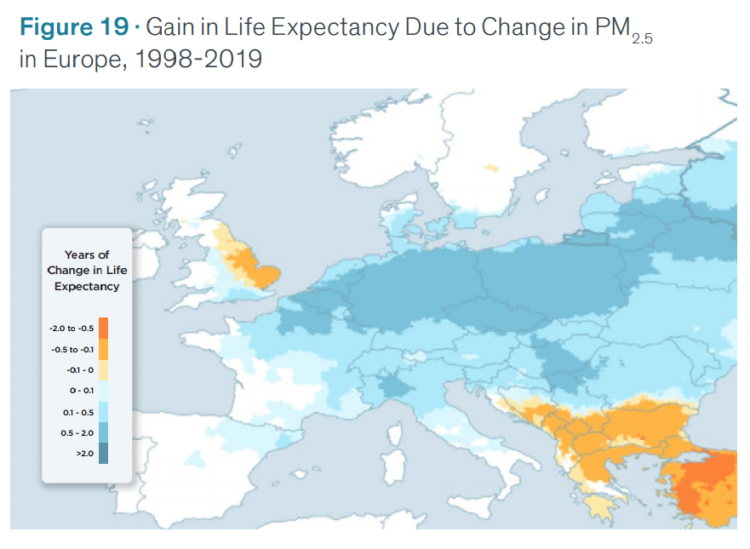

Air pollution is reducing our life expectancy by more than two years

The average global citizen loses 2.2 years of life with the current levels of air pollution, with residents in the most polluted cities lose up to five years of their lives, according to a new study. While bleak, the researchers behind the findings say this is an opportunity to improve, especially after the significant improvements in China over recent years.

The Air Quality Life Index (AQLI), compiled by researchers at the University of Chicago, found that air pollution remains a severe problem in many parts of the world, despite the momentary improvements brought by the COVID-19 pandemic. The researchers largely blamed fossil fuels from power plants, vehicles, and other industrial sources.

The researchers work with existing high-resolution satellite data, which helps to understand the level of air pollution. They then use ground-level monitors to assess the level of accuracy. Using this information, they are able to estimate the number of years people lose because of exposure to air pollution surpassing acceptable levels.

“During a truly unprecedented year where some people accustomed to breathing dirty air experienced clean air and others accustomed to clean air saw their air dirty, it became acutely apparent the important role policy has played and could play in reducing fossil fuels,” Michael Greenstone, creator of the AQLI, said in a statement.

The report found that we are all exposed to more than three times the air pollution considered acceptable by the World Health Organization, with life expectancy dropping from 74 to 72 years. Levels of PM 2.5, fine particulate matter, are at 32 micrograms per cubic meter on a global average, instead of the WHO advised 10.

Particulate matter, small airborne particles, is mainly generated by sources related to combustion such as wildfires, transportation, industrial emissions, and chemical reactions of pollutants. This has turned air pollution into a leading cause of death around the world, killing more than car collisions, smoking, or HIV/Aids.

A regional outlook

The researchers highlighted the significant progress of China in recent years, which shows that air quality can be improved in the short term with strong policies. The country began a “war against pollution” in 2013 and since has reduced its particulate pollution by 29%. This has added 1.5 years to the life expectancy of Chinese citizens.

Other countries could achieve the same level or even better levels of progress, even the most polluted ones, the researchers argued. In Southeast Asia, air pollution is now a major threat in big cities like Bangkok and Jakarta. The average resident there could gain two to five years of life expectancy if pollution levels are reduced so as to meet the WHO guidelines.

In Central and West Africa, the report found that the effects of air pollution on life expectancy match those of well-known threats such as malaria and HIV. In the Niger Delta, for example, with plenty of illegal oil refineries operating in the area, life expectancy is 4.7 years lower than what it could be if the WHO guidelines would be met.

Meanwhile, in Latin America, more than half of the 611 million people are exposed to unhealthy levels of air pollution. Although the average gain in life expectancy from cleaning the air is relatively low across the continent (roughly 5 months), the number is substantially higher in Latin America’s hotspots. For example, it’s 4.7 years in Lima, Peru.

“The events of the past year remind us that air pollution is not a problem that developing countries alone must solve,” Ken Lee, the director of the AQLI, said in a statement. “Fossil-fuel driven air pollution is a global problem that requires strong policies at every front—including from the world climate negotiators who are meeting in the coming months.”

The report can be found here.

1 September 2021

zme science