At the recent Cop27 climate talks in Egypt, government negotiators debated late into the night over what signals to give on which countries should receive funds to address the loss and damage caused by climate change.

The G77+China bloc of developing countries wanted all developing countries to be eligible for the funds. The European Union – which caused a lot of climate change and so will be expected to pay into the fund – wanted the money to only go to “particularly vulnerable” developing countries.

In the end, the two sides settled on agreeing to set up a funding arrangement and funds “for assisting developing countries, especially those that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change”.

That sets up a battle over how to define which developing countries are “particularly vulnerable”. That battle will be fought over the next twelve months by the 24 members of the new transitional committee.

What does vulnerability mean?

Vulnerability to climate change has three aspects. Is your country at risk of floods, storms, heatwaves, droughts, sea level rise and all the other nasty things climate change can throw at you? Are there people and precious things in the areas of the country at risk? And does your country have the money, experience and government capability to deal with these disasters?

Some countries, like Australia and the USA, are geographically vulnerable to fires, heatwaves and droughts but have the money to deal with them. Others, like Mongolia or Libya, don’t face any particularly severe climate threats but would struggle to deal with any that they did.

Measuring vulnerability by country is difficult and inherently flawed. Climate change is felt by people not nations.

The Notre Dame Institute judges Switzerland to be the least climate vulnerable country and Niger to be the most vulnerable. But an elderly homeless person in Switzerland will find it harder to deal with a heatwave than the president of Niger does.

As the Adelphi think-tank’s Janani Vivekenanda told Climate Home: “If you want to ensure that the most vulnerable are getting the support that they need, this is often at the sub-national level. You have pockets of fragility, of communities that are particularly vulnerable because they are politically excluded. They are marginalised communities, they are not part of the state architectures.”

What does the EU want?

Of the wealthy nations, it was the EU that first ended its decades-long resistance to dedicated loss and damage finance. It was then the bloc most active in placing conditions on that support.

Its negotiators have been tight-lipped over who they want to exclude. The European Commission’s climate lead Frans Timmermans said at Cop27 that China should pay into a loss and damage fund, which implies that it wouldn’t be a beneficiary.

The European Commission’s chief negotiator Jacob Werksman said at a Politico event recently that the UN climate convention’s classification of developed and developing countries, based on who was a member of the OECD in 1992, is out of date.

He added: “We have to reach the particularly vulnerable. It’s still for the negotiators to work on what that means. For us, I think it means setting a priority that really does focus on the countries that are recognised as vulnerable from both a physical and economic point of view but also takes into account vulnerable communities in countries that might have capacities as a whole that might describe them as middle-income in nature.”

In UN climate talks, particularly vulnerable has been used to mean small island developing states (Sids) and the world’s poorest countries – known as least developed countries (LDCs). This would exclude countries like Pakistan, which suffered catastrophic floods this year.

Timmermans clarified at Cop27 that “particularly vulnerable” would extend to Pakistan, in his view.

What do developing countries want?

In United Nations climate talks, 134 developing countries are represented by the G77+China bloc. After Cop27 ended, their chief negotiator on loss and damage Vicente Yu tweeted that “all developing countries are particularly vulnerable”.

He told Climate Home that the characteristics of being particularly vulnerable, as defined in the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the 2015 Paris Agreement, are applicable in one way or another to all developing countries.

The UNFCCC says that “low-lying and other small island countries, countries with low-lying coastal, arid and semi-arid areas or areas liable to floods, drought and desertification, and developing countries with fragile mountainous ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change”.

It adds to the list “countries whose economies are highly dependent on income generated from the production, processing and export, and/or on consumption of fossil fuels and associated energy-intensive products” and “landlocked and transit countries”.

Indeed, this definition is broad enough to include every nation in the world.

What do the poorest countries want?

Senegal’s Madeleine Diouf represents the smaller, poorer group of countries known as the LDCs. Diouf pointed to the narrower interpretation offered by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). She said: “There is a definition for loss and damage, where the existing capacity of the country is key.”

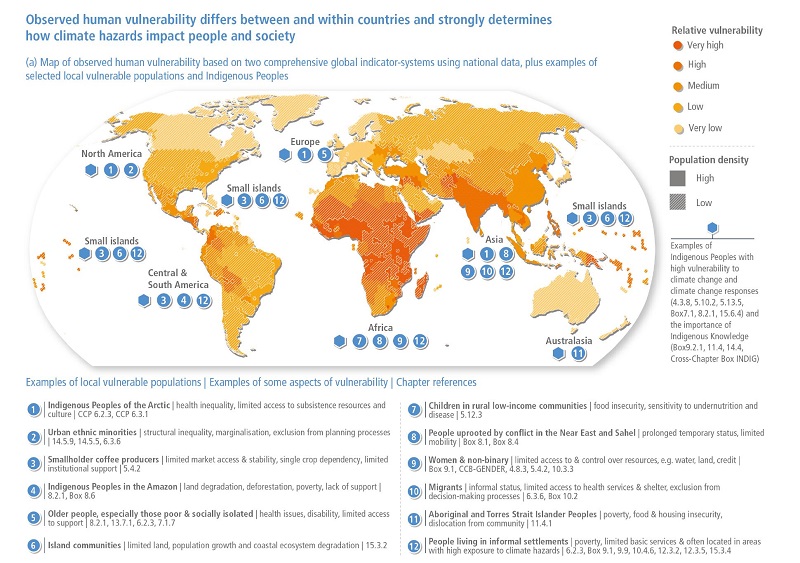

In a 2022 report, the IPCC defined vulnerability as “the propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected” and said it “encompasses a variety of concepts and elements, including sensitivity or susceptibility to harm and lack of capacity to cope and adapt”.

They added: “Global hotspots of high human vulnerability are found particularly in west, central and east Africa, south Asia, central and south America, small island developing states and the Arctic.”

Those hotspots cover all of the developing world except southern Africa, north Africa, the Middle East, southeast and east Asia. These regions are generally wealthier.

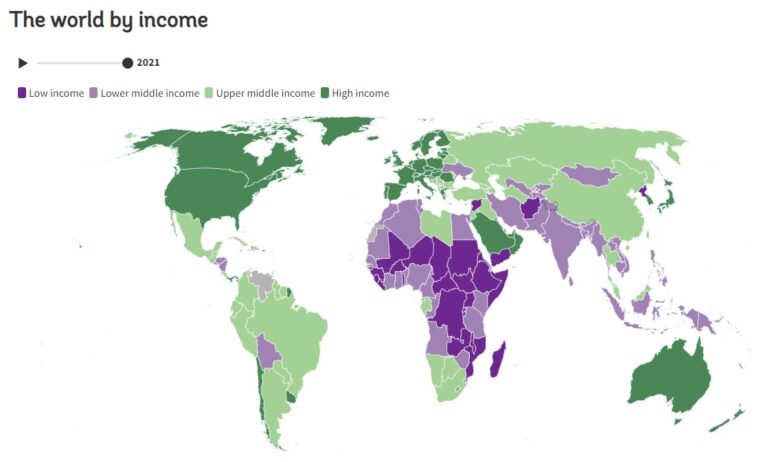

High income countries are in dark-green. Upper middle in light green. Lower middle in light purple. Least developed in dark purple. (Photo: World Bank)

In its loss and damage fund proposal, published before Cop27, the small island negotiating group (Aosis) uses similar language to that pushed by the EU. It stresess the need to protect “the vulnerable especially the particularly vulnerable such as Sids and LDCs”.

How do you measure vulnerability?

In March 2022, the IPCC tried to map vulnerability. It was contentious, giving a flavour of the battle to come.

Its classification was based on the INFORM Risk Index and the World Risk Index, which use indicators such as access to basic infrastructure and health care, nutrition, extreme poverty levels, literacy rates, inequality, governance and perception of corruption.

It did not take into account exposure to sea level rise, storms, heat stress or floods – now or in future projections. That reflected a lack of consensus on how to compare the severity of various climate hazards.

On this basis, much of sub-Saharan Africa was judged to have “very high” vulnerability. China was “medium” while much of the Arabian Gulf, much of South America and parts of southern Africa were “low”.

Some government representatives expressed concerns the national averaging couldn’t account for differences within countries. Others considered criteria on governance and corruption as policy-prescriptive and biased towards wealthy nations. They did not approve it for inclusion in the report’s “summary for policymakers”.

A draft map on observed human vulnerability which was deleted from the report’s summary for policymakers. A similar map was published in the full report. (Source: Draft SPM IPCC Working Group II)

The US-based Notre Dame Institute combines geographic factors with countries’ ability to adapt for a more precise ranking. To measure a country’s food system vulnerability, it forecasts how much cereal yields will change, how dependent a country is on food imports and its agricultural capacity.

It placed China at 68 out of 182 countries with adequate data, where a low number means less vulnerable.

Ultimately, vulnerability is not static. Who gets money will be determined as much by political relations and resources available as objective indicators of need. For rich countries, that may come down to: not China.