We could power households from the scraps in our food waste bins – here’s what is stopping us

Imagine if you could power your kettle using the energy generated from the vegetable cuttings quietly breaking down in your kitchen’s compost bin. That reality might not be so far off with the growth of biogas technology.

Biogas is a green alternative to fossil fuels that not only helps to reduce toxic emissions but also provides cheap, clean energy. It’s made up of a mixture of methane, carbon dioxide and a little hydrogen sulphide and water vapour, all of which is produced by microbes that live on organic raw material within a airtight digester container.

The efficiency of the system depends on the size and insulation capability of the digester, as well as the quantity of methane produced from the “feedstock”, which can be anything from carrot leaves and onion peels to residue from gardening.

Biogas is “green” because it reduces the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere from decomposing food waste. Instead, these gases are stored and used for generating heat and electricity, making the energy produced from waste more sustainable.

Yet although biogas has been promoted as a way of helping to reduce carbon emissions for a few years now – and has actually been used to power households since as early as the 10th century BC (for heating bath water in the Middle East) – it still only represented around 0.004% of total EU gas consumption in 2019. So why is uptake so low, and what can be done about it?

Digesters in practice

Micro-digesters (between two to ten cubic metres) can power individual household systems for up to 12 hours per day, while large digesters of 50 cubic metres can be linked to the local gas grid to support communities for up to 250 hours.

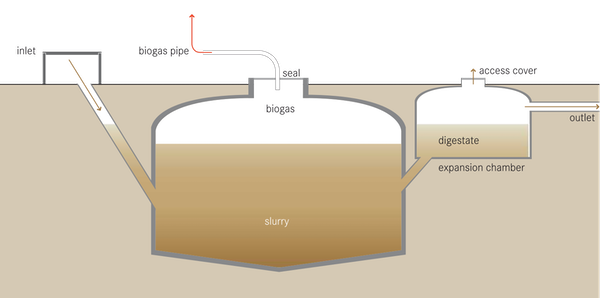

The diagram below shows how these systems usually work: the pipe at the top of the image would normally lead to a community gas tank or household appliance.

How they work in practice

An example of an innovative small-scale biogas system is the Methanogen micro-digester. There is one running at Calthorpe community garden, a multi-functional urban community centre in Islington, London. The unit sits in a repurposed shed next to a vegetable garden. The energy, generated from food and garden waste from the surrounding houses, is supplied to the centre’s kitchen hob through a pipe.

The digester is run by community volunteers, whose mission is to improve the physical and emotional well-being of residents living in the centre’s surrounding areas by encouraging them to grow food and spend more time in nature.

An even more ambitious initiative is running on the Swedish island of Gotland, where an eco-village, Suderbyn, has been created using zero-carbon materials. A community-run digester was set up to create heat using food and agricultural waste from the community. Inspired by Suderbyn’s success, similar sites have been launched in the UK at Hockerton, near Nottingham, and in Grimsby.

The uptake problem

But why are more digesters not springing up? Our research set out to understand the challenges responsible for the slow uptake of this technology.

To better understand people’s attitudes towards biogas, we carried out a study of community biogas generation in Europe. Our research, conducted through interviews and consultation workshops, found that one of the barriers stopping biogas use was prejudice arising from poor public understanding of the technology and its benefits.

People we spoke to were concerned that local digesters would produce a nasty smell, or that their industrial appearance would blight the landscape. In fact, many digesters are fairly small, and would only produce smells if the system broke down.

Other stumbling blocks include a lack of technical expertise in building or maintaining digesters, a lack of incentives to attract local businesses, and the high cost of the digester, which – depending on its size – can cost between £12,000 and £158,000.

Because of this, local government assistance will be crucial in bringing biogas to the masses. They should help shoulder the financial cost or provide seed money to groups interested in setting up biogas systems. Councils will also need to facilitate the collection, handling, transport and storage of food and garden waste, which usually takes place weekly; and deal with hurdles such as arranging planning permission for larger digesters.

Community engagement with projects like this is also vital. Biogas initiatives, especially larger ones, can only become a success when there is trust and cooperation between the community members who would be running the system and sharing in its spoils. Both a motivated community and supportive local policies are necessary ingredients for a biogas project to flourish.

Using biogas to generate renewable energy has the potential to significantly speed up decarbonisation – reducing a country’s carbon output – by helping to make the energy supply chain more sustainable in the long run. But without government support, the future of biogas remains uncertain.

August 2021

INDEPENDENT