UK coronavirus deaths more than double official figure, according to FT study

FT estimate has been updated to reflect latest mortality trends.

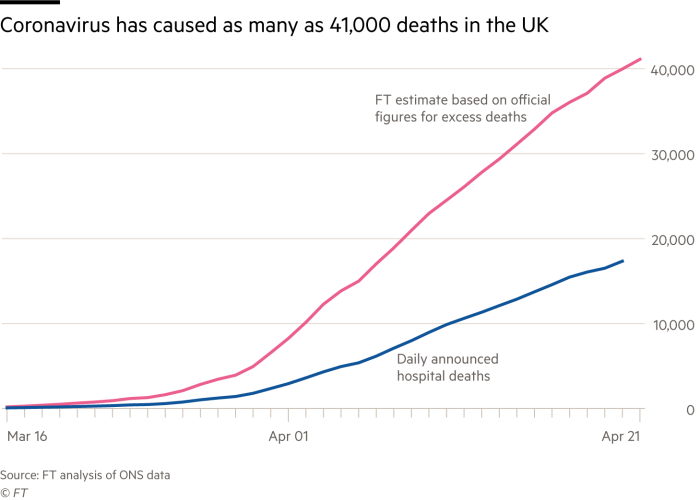

The coronavirus pandemic has already caused as many as 41,000 deaths in the UK, according to a Financial Times analysis of the latest data from the Office for National Statistics.

The estimate is more than double the official figure of 17,337 released by ministers on Tuesday, which is updated daily and only counts those who have died in hospitals after testing positive for the virus.

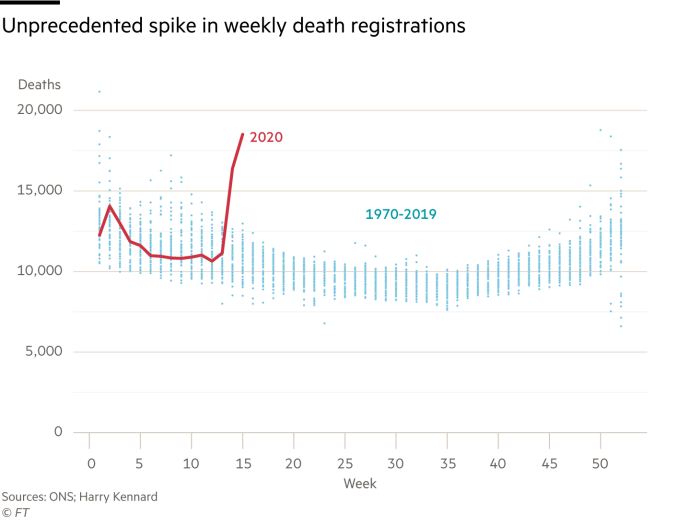

The FT extrapolation, based on figures from the ONS that were also published on Tuesday, includes deaths that occurred outside hospitals updated to reflect recent mortality trends. The analysis also supports emerging evidence that the peak of deaths in the UK occurred on April 8 with the mortality rate gradually trending lower since, despite the 823 hospital deaths announced on Tuesday, which were sharply up on the 449 in the previous 24 hours. The ONS data showed that deaths registered in the week ending April 10 were 75 per cent above normal in England and Wales, the highest level for more than 20 years.

There were 18,516 deaths registered during that period compared with the most recent five-year average of 10,520 for the same week of the year. There were similar patterns in Scotland and Northern Ireland Nick Stripe, head of life events at the Office for National Statistics, said the figure was “unprecedented”, especially as the weather had been sunny and warm in the run-up to the Easter weekend. He added that because the week included Good Friday, when registrations were much lower than on a normal working day, the ONS numbers were also “conservatively” at least 2,000 too low.

The number of deaths in the UK has moved from running at below long-term averages to well above them as a result of the pandemic. Excess deaths from all causes stand 16,952 above the seasonal average across the UK since fatalities from Covid-19, the disease caused by the virus, began to mount in mid-March.

The “all cause excess mortality” figure is widely recognised as the best measure of the death toll linked to the pandemic. David Spiegelhalter, the Winton professor of public understanding of risk at Cambridge university, said it was “the only unbiased comparison” given the problems measuring deaths and their causes.

But because of the lag in collating the data, the ONS published figures for the period to April 10 are significantly out of date as they are based on registrations received by the statistical office, which on average arrive four days after the actual date of death.

The FT’s analysis has extrapolated these figures using the latest trends in the daily hospital deaths assuming the relationship between these and total excess deaths remained stable, as it has so far over the course of the pandemic.

Using this calculation, a conservative estimate of UK excess deaths by April 21 was 41,102.

Carl Heneghan, professor of evidence-based medicine at Oxford university, said the deadly effects of Covid-19 were much more marked than during a bad outbreak of seasonal influenza.

“I don’t think we’ve ever seen such a sharp upturn in deaths at that rate,” he said. The 2017-18 seasonal flu outbreak may have killed 50,000 in the UK but “the reason we did not get alarmed then was that they were spread out over many weeks”.

The ONS data also showed that deaths at home and in care homes had also jumped sharply during the pandemic. In the week ending April 10, deaths in care homes reached 4,927, almost double the figure of 2,471 a month earlier.

Prof Spiegelhalter said that coronavirus was not given as the cause on many of the death certificates but was likely to be a direct or indirect factor. He said many doctors would initially have been reluctant to designate the virus as the cause on death certificates as it was a new disease and they could not have been certain.

Some of those who died from other causes may have been too scared to attend hospital or did not want to be a burden on the health service so they could be seen as possible indirect victims of the virus, he argued. But he added, the sheer number of deaths caused by the virus meant, “there is no suggestion that the collateral damage — however large it is — is anything like as big as the harm from Covid”.

The ONS said on Tuesday it had asked Public Health England to investigate why care home deaths were rising so sharply.

The FT has broken down its analysis for England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, as they report weekly deaths separately. There were almost 38,000 deaths to date linked to Covid-19 in England and Wales. In Scotland this figure is a little under 3,000 and just below 500 in Northern Ireland.

As 24 per cent of deaths normally occur in care homes in the UK, the analysis suggests that just under 11,000 more people than normal have died in residential care since the start of the outbreak.

Ian Hudspeth, chairman of the Local Government Association’s Community Wellbeing Board, described the ONS data as “sad and shocking” and said it highlighted the severe challenges being faced by care homes across the country.

“We are also yet to see the peak of the stress on the social care system, due to the delay between hospital admissions and discharge, which will require the need to start thinking about shifting capacity across from hospitals and into the community to meet a surge in demand,” he added.

The ONS data also showed that the vast majority of all excess deaths were people aged over 75 years old. This age bracket accounted for 70 per cent of the total, the same proportion as those with Covid-19 on their death certificates.

Prof Henegan said this was unusual for a pandemic and reflected the same patterns of mortality seen in seasonal flu epidemics. “In all the previous pandemics, the young are disproportionately affected,” he said.

22 April 2020

FINANCIAL TIMES