Shell Has a Plan to Profit From Climate Change.

Shell Is Looking Forward

The fossil-fuel companies expect to profit from climate change. I went to a private planning meeting and took notes.

“We think democracy is better,” said the jet-fuel salesperson. “But is it? In terms of outcomes?”

In a conference room overlooking the gray Thames, a group of young corporate types tried to imagine how the world could save itself, how the international community could balance the need for growth with our precarious ecological situation. For the purposes of our speculative scenarios, everything except for carbon was supposed to be up in the air, and democracy’s track record is mixed.

A graph from Chinese social media showing how many trees the country is planting — a patriotic retort to the Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg — had a real effect on the room. Combine that with the Chinese state-led investment in clean-energy technology and infrastructure and everyone admired how the world’s largest source of fossil-fuel emissions was going about transition. That’s what the salesperson meant by “outcomes”: decarbonization.

Regional experts from sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East–North Africa also entertained the democracy question, pointing to Iraqi disillusionment with voting and economic growth in Rwanda under Paul Kagame (“He’s technically a dictator, but it’s working”). The China expert said the average regional Communist Party official is probably more accountable for his or her performance than the average U.K. member of Parliament, a claim no one in the room full of Brits seemed to find objectionable. The moderator didn’t pose the question to me, the American expert, presumably because our national sense of democratic entitlement is inviolable.

Actually, the moderator didn’t ask me any questions during the plenary that followed our regional-perspectives panel, either. That might have had something to do with my talk, which included bullet points like “Green growth is a myth” and “Your corporate existence is incompatible with a livable future for cohorts that are already born.” But I didn’t get that impression, not really. I was repeatedly asked to be honest, and everyone was really nice about it. Everyone was really nice in general.

Since 2017, when I published a book about American millennials, I’ve had the occasional cold call from corporations to come talk about my work, all but one of which I’ve turned down. But last fall, the Shell Scenarios team — as in Royal Dutch Shell, one of the biggest oil companies in the world — offered me £2,000 in exchange for a 15-minute talk and my participation in a group exercise. Its internal corporate think tank was holding a daylong conference about how generational change would affect the hopefulness projected in what the company calls the “Sky Scenario,” which it describes as “a technically possible but challenging pathway for society to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.” I’m not a climate expert, but apparently I qualify as a generational whisperer, at least to Shell, and to talk to me about global warming, the giant energy conglomerate wanted to fly me to London from Philadelphia, business class. I warned them that I couldn’t keep their money and asked if I’d need to sign an NDA. When they said no, I saw an opportunity to report on the oil company, undercover while in plain sight, without technically lying to anyone. It was too good to pass up. I said yes, then I emailed my editor.

The October 2019 workshop, it turned out, was timely. Fossil-fuel divestment used to be a fringe, college-campus concern, but over the past year, it has become increasingly in vogue in the world’s financial centers, including Davos, where it recently dominated conversation at the World Economic Forum. In December, a couple of months after the Shell workshop, the Bank of England proposed a new climate stress test to measure the resiliency of its banks in the face of warming — a move echoing that of Christine Lagarde of the European Central Bank and reportedly being considered by the chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell. Germany announced major coal phaseouts in January with coal-fired power generation scheduled to halt by 2038 at the latest. In a much-celebrated letter the same month, Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, declared an about-face on fossil fuels, saying climate change was now a “defining factor in companies’ long-term prospects.” The entire country of Finland proclaimed it would go carbon neutral by 2035. Even the investor cartoon Jim Cramer, of Mad Money, got in on divestment, tweeting, “I am taking a hard pass on anything fossil.” Now ExxonMobil is down $184 billion-with-a-b since its 2014 peak.

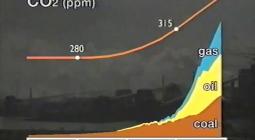

From a certain vantage, the momentum looks almost definitive, as though nothing could stand in the way of a renewable future. But unlike coal, oil and gas companies are still definitely profitable, even investable, and more oil and gas are being produced, and used, every year — which helps explain why carbon emissions keep rising too. There’s little doubt that fossil-fuels are, culturally speaking, on the wrong side of history. But there is still a lot more money to extract from those wells, and the fossil-fuel businesses are intent on extracting as much as they can. It’s not necessarily such a bad time to be an oil and gas company, in other words, but it is a bad time to look like one. These companies aren’t planning for a future without oil and gas, at least not anytime soon, but they want the public to think of them as part of a climate solution. In reality, they’re a problem trying to avoid being solved.

Few organizations have been paying as much attention to global warming for as long as the companies that have helped cause it. Journalists at the Dutch publication The Correspondent tracked down an educational video Shell released in 1991 called “Climate of Concern,” which warned, “Global warming is not yet certain, but many think that to wait for final proof would be irresponsible. Action now is seen as the only safe insurance.” There’s good evidence Exxon knew a decade earlier. But not only did these companies continue exploiting their reserves, not only did they explore for new sources and develop new modes of extraction, like fracking, but they funded politicians and groups that claimed not to believe in global warming, agents that have worked to delay the same action they knew was “our only safe insurance.” So far, the oil and gas companies’ calculations — that delay would make them money and that they could avoid consequences for misleading the public — have been spot on. But denial-backed delay is no longer sufficient, it seems. They’re now hoping to leverage their incumbency, and fossil-fuel wealth, to lay claim to the world’s clean-energy future as well. To do that, they’ll have to persuade young people to forget who caused climate change in the first place, or at least to let bygones be bygones. And if they can transition their corporate profiles from fossil fuel to green energy without missing a profitable quarter, that wouldn’t be a repudiation of their delay strategy; it would be a vindication.

Of course, to judge by the advertisements, the transition to renewables has already happened. British Petroleum is now a solar-energy company called BP, ExxonMobil brews giant swimming pools of cool green-algae fuel, and Shell maintains mountain canyons lined with wind turbines floating in fog. All these initiatives actually do exist, though they are a tiny fraction of each company’s budget; so far, the main product of Exxon’s algae program seems to be propaganda. Right now, these companies have to convince governments and their publics to let them run out the clock with fossil fuels, and they’ve decided the best way to do that is to appear to be an essential partner for whatever’s coming next. I was ostensibly there to help plan the timing.

Organizers broke the conference up into three parts: first, a panel on polling and millennial politics; then the regional-perspectives panel; and finally, a collaborative exercise in which “deductive” and “inductive” groups imagined different paths to 2050. By gathering millennial employees from throughout the company, along with experts on the cohort and senior management, the strategies team surely hoped to infuse the firm’s leadership with a drip of youth consciousness, the way some oligarchs are rumored to inject themselves with young people’s blood. It’s supposed to help them stay agile. Other than the eight outside experts, there were a couple dozen people from Shell, ranging from HR specialists in their 20s to senior global executives (mostly Gen X and boomers). Staffers quoted me the figure “90,000 employees” (roughly the size of the company as a whole) a few times when explaining that virtually none of them knew one another.

Some of the most revealing insights came the night before the sessions at a group dinner at a minor Gordon Ramsay restaurant. The venue had two party spaces, and it wasn’t immediately clear where we were supposed to go, but when someone suggested putting up a sign rather than having wait staff direct the party one by one, the younger Shell employees grimaced. “Extinction Rebellion,” one said, less than half-joking. The climate-protest group has a major presence in the city with flyers and volunteers everywhere. “XR” targeted Shell locally in April 2019, smashing windows at the company’s London headquarters. In the U.K., it has succeeded at creating an ambient sense of fear or at least shame. We gathered in the mezzanine dining area and milled around doing introductions, and I asked young workers from the far-flung corners of the Shell empire, “Oh, what’s that like?” I tried to remember not to talk like a reporter.

When they called us to the table for dinner, I was lucky enough to be seated next to one of the senior Shell participants, Steven Fries, the firm’s chief economist. We met over arancini, the likes of which you might find at an upscale food court in a baseball stadium. Based in Shell’s global headquarters in the Hague, Fries pronounces his words with a precision that defies accent; even after speaking with him, his colleagues didn’t realize he’s an American until he told them. Like many people who studied economics at elite Western institutions between 1975 and 1986 would, he blames the lack of affordable housing in London on too much government regulation, which is why his support for big public investments to transition society away from oil and gas surprised me. That is, until I realized that, in his mind, those big public investments would be going to energy companies. When the proverbial light bulb went on above my head, he gave me a look that seemed to say, “Come on, man. What do you think we’re doing here?”

"We’re going to get as much out of [oil and gas] for as long as we can."

In the corporate sector, there’s still faith at the top that economic incentives and profit-seeking behavior can manage the crisis that capitalism has wrought. In such thinking, climate change is like a redux of the hole in the ozone layer: potentially bad but solvable with the tools on hand and without real changes to our lifestyles. Fries estimates that we’ll be able to cost-effectively fill two-thirds of world energy demand with clean sources within 20 years. (That’s ten years more optimistic than the optimistic scenario of the International Renewable Energy Agency, an intergovernmental organization mandated to propagate optimistic scenarios about renewable-energy transition.) Even if that kind of turnaround is unrealistic, the Shell plan isn’t so different from the mainstream climate left’s agenda. A recent paper from Stanford professor and renewable advocate Mark Z. Jacobson calls for $73 trillion in spending to transition most of the world’s power grids no later than 2050, and he and his co-authors figure it’ll pay for itself in energy savings alone within a decade. In the analysis of Jacobson and other Green New Deal supporters, how many of those trillions end up going to Shell is largely beside the point. But for Shell, that’s the whole ball game.

In the meantime, I asked Fries, if Shell is serious about transition, then couldn’t it voluntarily speed it up by leaving some of its wells fallow, constraining oil output and thereby driving the price relative to renewables higher, faster? Sure, it would have to take some losses in the short term, but we’re talking about the future of the planet here. He dismissed the idea, telling me it’s important not to artificially withhold supply, which would introduce price shocks that could turn public opinion against environmentalist policy. Besides, it would only end up sending money to the Saudis anyway.

“We’re going to get as much out of [oil and gas] for as long as we can,” he said.

“That’s an extremely frightening thing for you to say,” I said.

“It doesn’t mean every drop,” he said, failing to reassure me.

Shell would apparently prefer us not to think about how to reduce carbon emissions by raising the costs of fossil-fuel development. Which makes sense: No matter their green branding, fossil-fuel companies do not want their projects rendered uneconomic. Instead, they want to talk about how their new projects can be rendered economic faster. Even planned production from existing fossil-fuel infrastructure, it’s been estimated, will push the planet past the Paris targets, and Shell is still “exploring” for new oil deposits to exploit. “In terms of emissions, it’s one of the cleanest ways to go,” a Shell employee in deepwater strategy seated across from me explained about deepwater drilling as compared with other kinds of drilling. “Of course, when you put it in your car and burn it, it’s oil, but,” he said, trailing off. Although the slice of revenue energy firms derive from fossil fuels is by all accounts scheduled to shrink, Shell foresees a sizable enduring demand. No one has viable plans for a battery-powered container ship, and the world’s militaries aren’t about to give up jet fighters pending the development of an electric model. Not to mention that all this clean technology requires a lot of energy in advance for manufacturing. Deepwater wells operate on a ten-year schedule, I’m told, so my dinner companion doesn’t expect the ones he’s looking at now off the coast of Brazil to even yield product until the 2030s, at which point it will take more time just to earn back the initial investment and even longer to turn a profit.

In February, Shell announced the purchase of a 50 percent operating stake in three deepwater blocks off Colombia’s Caribbean coast under an agreement with Colombian state-controlled Ecopetrol. And Shell’s not the only one looking in the water off South America: In January, based on exploration in late 2019, Exxon revised its estimate upward for its blocks off Guyana, from 6 billion barrels of recoverable crude to 8 billion. (A week later, the nonprofit watchdog Global Witness released a report estimating that Exxon’s 2016 agreement with the country, negotiated with inexperienced government counterparts, had deprived the Guyanese people of $55 billion compared with international contract norms.) Fossil-fuel companies claim they’ve got one eye on 2050, but they’ve clearly got the other on next week. “If these activities are positive, these discoveries could be developed and potentially be a substantial increase in gas supply in the medium term,” a Shell spokesperson said of the Colombian offshore blocks, as if that would be a good thing.

But if short- and medium-term profit considerations are still driving plenty of decision-making at Shell and the other energy companies, employees are trying to think ahead when it comes to their careers. During the cocktail hour before dinner, I met a geoscientist who has been attempting his own transition (to the finance side of the business), preparing to move from the declining subsurface field to clean tech. I asked how he got involved in oil exploration in the first place. A little embarrassed, he told me he liked rocks as a kid. When he graduated from college, he saw two career paths: the energy sector or academia, where he would just be training others for the energy sector anyway. He said he was worried about the next generation of Earth-science students, who are graduating into a shrinking industry. Maybe they’ll be mining asteroids, suggested the deepwater strategist.

According to the geoscientist, one of the ways Shell incorporates climate change into its calculations is that when it looks to develop a new fuel source, it tries to figure out how much it’ll be able to sell it off for when the company transitions out of fossil energy — when the reputational costs start to exceed the returns. Whoever buys it will almost certainly continue extracting but at a lower cost of production, maybe because it has better technology or, more likely, because it cuts corners on labor and safety. What this means: Unregulated fossil-fuel production might come to look a lot like the narcotics trade, with its brutal criminal organizations that thrive in conjunction with corrupt state elements regardless of international agreements. The problem is that once reserves are discovered, there’s no way to undiscover them. “We don’t plan to lose money,” the geoscientist turned finance analyst said, and he meant it in the most general way.

The whole session was conducted under “Chatham House Rule,” which means participants are allowed to repeat what they hear but not who said it. The idea behind the rule is that it creates circumstances under which subordinates can speak freely to higher-ups about the company without endangering their career path. (As an American reporter, I am ignoring the rule when I see fit, having technically never agreed to anything.) The deepwater strategist put it to the test, prodding the senior executive Fries about the generational implications of green regulation. Was Fries, he wondered, going to help pay for the new electric car he’ll have to buy if the internal-combustion vehicle he just saved up enough to purchase is banned?

At a pub after dinner, away from the executives, the deepwater strategist confessed that he often thinks about what he’ll have to tell his child someday about the job he’s doing now. “I don’t have any kids, but, yeah,” the geoscientist agreed. He didn’t know how to describe the people to whom he owes an explanation, but he knows they’re out there.

The biggest gap in politics right now is generational, the Harvard polling expert told us. “This is a two-thirds generation in a 50-50 country,” he said, meaning that millennials are much more reliably progressive than the country as a whole. This makes sense. Young people are fearful, they have little trust in institutions, and they’re dealing with high levels of stress and anxiety. This has led to generational tension, especially around the existential challenge of climate change. One of the session’s recurring themes was that millennials and Gen-Zers have a stronger moral and ethical drive than their elders, and they expect us to use our values to help force companies to do the right thing. But Shell doesn’t seem to fear attacks on its brand from consumers, since most of its business is with other companies, and even when it comes to customers, most people don’t make choices about where to buy gas based on the relative climate villainy of the respective oil companies. On top of which, its product is not very recognizably branded. “Jet fuel is jet fuel,” I was told. Instead, it’s worried about being left behind by the curve of social change, that if it doesn’t become more than an oil company, it’ll stagnate, wither, and eventually die.

We were tasked with trying to come up with ways Shell could see what’s coming, and participants began by imagining various ways Shell would feel this “rise of a new ethics,” as one of the experts called it: millennial politicians forcing harsher regulations, millennial investors divesting from fossil fuels, millennial potential recruits who don’t want to be embarrassed about their work, and millennial protesters who push everyone else. Shell strategists used the phrase “long march through the institutions” — coined by the German communist Rudi Dutschke for the ’60s student movement — to describe the way they expect left-wing climate radicals to become part of the Establishment.

This may seem like a progressive outlook and a surprising one for a fossil-fuel company that has faced the ire of climate protesters so directly. But Shell doesn’t seem to see the climate movement as the enemy or even necessarily contrary to the company’s interests. If Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is going to rally millennials around Green New Deal legislation, then it’s a good time to become a green-energy company — or at least buy a few of those and rebrand that way. Climate protesters are just another market reality, one that can be profitable when apprehended correctly, even for a big, old oil and gas firm. The question was how to see that generational conflict coming, how to meet it and harness it and ride it into the future.

"We don’t plan to lose money."

The youth climate movement is winning plaudits now, but it didn’t start with Greta, and the lessons from those previous eras are not especially encouraging. Ten years to the month before the Shell conference, I was lying down on the concrete walkway in front of the Bank of America in College Park, Maryland, part of a die-in against financing for mountaintop-removal coal extraction. That same year, I attended a Power Shift youth climate conference, which ended one freezing March morning with thousands of us blocking the power plant serving the U.S. Capitol. One of my fellow shivering demonstrators was Shana Rappaport, who recently reflected on how her thinking has changed:

As I stood on the hill in my fuzzy winter hat … protest sign in hand, trained and prepared for the prospect of getting arrested, I believed wholeheartedly in the message we were chanting: “The enemy is profit. Together, we will stop it! Climate devastation will not be solved by corporations!”

I never would have imagined that, a decade later, my perspective would have shifted so significantly. Specifically, my belief that we have a better chance to build a sustainable future by engaging with as many companies, industries, and individuals as possible. And that includes oil companies.

After all, accelerating the transition to a clean economy requires all hands on deck, including the hands of those that have contributed most significantly to the problems we are working to address.

Rappaport is now the vice-president and executive director of VERGE from GreenBiz, which is, according to her LinkedIn, “the leading global event series focused on accelerating the clean economy and solutions to the climate crisis.”

And even the Shell antagonists at XR are friendlier to corporate thinking than their public profile would suggest. In an interview with the New Left Review, XR spokesperson Zion Lights explained that, in contrast with the consensus model of decision-making favored during Occupy, the group uses a “self-organizing system based on features of the Holacracy model.” Holacracy is a decentralized management program whose most prominent user is the Amazon shoe subsidiary Zappos. In the interview, Lights suggests that “the billions poured into fossil-fuel subsidies could be diverted into cleaner energy and technology.” If you’re Shell, the ideal compromise would be to simply add the green subsidies on top of the oil and gas subsidies. That’s not actually a compromise; it’s just an increase in giveaways to energy companies. But Shell’s going to make it sound like it’s meeting the climate movement halfway by taking billions to trillions of dollars in taxpayer money to jump-start its green divisions.

For the visioning exercise, I was put in one of the “deductive” groups; organizers gave us two scenarios for the world in 2050 and told us to work backward to the present to imagine a 2020 approach that would get us to the 2050 target. Both deductive groups did Scenario 1: Concerted global cooperation enables us to meet the Paris-climate-accord goals, moving us past the peak of greenhouse-gas emissions and limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. But personally, I wasn’t interested in helping Shell psych itself up for a timeline in which it saves the world and gets paid doing it. Instead, I pressured the members of my group to think about everything else, everything that could go wrong while decarbonization goes right. This seemed, in a way, mutually productive: They know much more about the sector than I do, and I genuinely wanted both their answers and the opportunity to demonstrate that there was more to solving a problem of global political economy than drawing decarbonization lines up and to the right on a dry-erase board. With one vaguely offended exception — a “strategic-projects manager” called me “cynical” — everyone was happy to give it a try.

I prompted them: If we rapidly expand nuclear-energy production, we’re probably going to see more nuclear accidents, right? I was thinking about the recently deceased French philosopher Paul Virilio, who liked to point out that with every new technology, we also invent new ways for things to go wrong. “Oh, China is due for a big nuclear accident,” said Wim Thomas, Shell’s genial Dutch chief energy adviser. The China expert — also in my group — suggested waste was a huge, unexamined issue. Where are we going to put all the solar panels when they break? Bloomberg has reported on the massive used wind-turbine blades that are so durable they end up in landfills. We talked about corruption, how governments in the global South buy certain pieces of expensive industrial equipment because manufacturers know whom to bribe, a practice that’s bound to increase when there’s all sorts of miracle decarbonization tech floating around. Land use is a big problem, whether it’s for wind or biofuel. We also have to figure that, no matter what metrics we end up using to gauge progress, there’s likely to be some fraud. That’s what ProPublica found when it went looking for the forests that all those “carbon offsets” were supposed to pay for — basically none were working the way they had been sold to guilty Western liberals and greenwashing corporations, as a method of keeping carbon in the ground. By the time we finished with the trade-offs in Scenario 1, we barely had any time for the less rosy Scenario 3: nationalism and corporate geoengineering. Think green border walls and paying Elon Musk to turn down the sun. That’s the alternative to successfully reducing emissions.

Then the groups regathered and presented their work. When members of the other team gave their version of Scenario 1, the first step they imagined was a co-optation of the youth environmental movement by older generations and their institutions. Co-opt was the word they used, but they meant it in the positive sense: the end point of being influenced. Liberated from the dour marchers, the Establishment will tweak the messaging from XR-style fear for the immediate future of the species to classic Obama hope and change. There will be “youth innovation hubs” and millennial investors bringing their values to the market, eager to provide capital for clean-energy start-ups. The night before, I had learned Shell was moving into new sectors in part by buying up small firms like Greenlots (electric-vehicle-charging infrastructure) and Sonnen (smart batteries). Some of the younger Shell employees I spoke to had found themselves acquired into jobs they wouldn’t necessarily have applied for. That’s one way around a recruiting problem.

Before I left for London, I had reread a piece in the magazine Commune about challenges that will be hard to avoid for any growth-based green transition. In “Between the Devil and the Green New Deal,” Jasper Bernes looks at some of the double binds the global profit system puts us in.

If you tax oil, capital will sell it elsewhere. If you increase demand for raw materials, capital will bid up the prices of commodities and rush materials to market in the most wasteful, energy-intensive way. If you require millions of square miles for solar panels, wind farms, and biofuel crops, capital will bid up the price of real estate. If you slap tariffs on necessary imports, capital will leave for better markets. If you try to set a maximum price that doesn’t allow profit, capital will simply stop investing. Lop off one head of the hydra, face another.

At dinner, I tried to get Fries, the economist, to answer some of the article’s questions: How can we move to clean energy without intensifying resource extraction in certain parts of the world? Where are we going to get the lithium for all these new batteries? Won’t Shell’s plans still mean creating ecological dead zones, in effect writing off whole regions of the Earth? And what will happen to the people who live there? I told him that, in June, a couple of miles from where I live in Philadelphia, an oil refinery exploded, releasing 3,271 pounds of toxic hydrofluoric acid into the atmosphere and launching a truck-size piece of shrapnel to the far bank of the Schuylkill River, over 2,000 feet away.

Those are real concerns, he conceded, though clearly not the ones that preoccupy him as the chief economist for Shell.

“There’s a lot of energy in this room,” Fries said, gesturing around our dining area. “We have to find a way to keep supplying it.”

The lights were tastefully dim, but I knew what he meant: There was the mediocre piece of fish perfectly replicated on each of our plates, the exorbitantly expensive airplane ticket that brought me to the table, the oil they sold to pay the participants’ salaries. Shell’s concern, deeper than its fossil-fuel identity and more urgent than the climate crisis, is Shell. I don’t believe it’s going to lead us to the Paris climate goals, and Shell probably doesn’t believe it will either. But in order to survive and keep the bottom line growing, I am convinced the company will do whatever needs to be done, whether that’s networking solar panels, systematic human-rights violations, or both. Maybe it’ll even make some incidental progress along the way, depending on where the subsidies are, but there’s no comprehensive vision for a livable future here, no ethical imagination, no morality to speak of. It is unfit to lead.

To make a point about how the company is prepared to handle resistance from protest groups, I asked Fries (rhetorically) who killed Ken Saro-Wiwa, an environmental activist in the oil-rich Niger Delta who was executed along with eight of his comrades in 1995. In 2009, Shell settled with the victims’ families out of court for $15.5 million, though to this day the company denies any wrongdoing. Fries deadpanned, “I believe that was the Nigerian government.”

“I just don’t see where the guardrails are,” I said. “We know how companies like yours have handled these problems in the past. What’s to stop you from forcing the poorest people and places in the world to bear the very heavy costs of this transition?” I think I left the “while you keep profiting” implied.

“We have a strong civil society,” he said, off-loading responsibility again. “And freedom of the press.”

I fear that won’t be enough.

3 March 2020

Intelligencer