Saudi Arabia’s World Is Coming Undone.

Bulls are banking on the kingdom this week, but its future role could be far more disruptive.

Saudi Arabia is having a regular week: Facing off against Russia, taking phone calls from the U.S. president and supposedly cobbling together a plan to save the (oil) world. On Thursday, it will preside over an emergency meeting of OPEC+; the next day, a virtual gathering of G20 energy ministers.

As opportunities to strut the global stage go, this one comes at a big cost: Like most oil exporters, the country faces a cataclysmic drop in demand. But this isn’t just about the money. A new book lays out why the Covid-19 crisis offers a taste of a far-bigger problem: Saudi Arabia’s world is coming apart.

“Disunited Nations,” by geopolitics analyst Peter Zeihan, is a typically engaging read, but it is not a happy book. Zeihan contends the postwar global order that rested largely on U.S. sponsorship (or attention, at least) is unraveling. After seven decades of America suppressing humanity’s tendency toward general mayhem, more or less, with a muscular commitment to free trade and blanket security guarantees, a more Hobbesian future beckons.

Few countries have been shaped by the Pax Americana quite like Saudi Arabia, which gets its own chapter. A sparsely populated, largely desert kingdom that emerged from clan warfare amid the ruins of the Ottoman Empire, it would have been a geopolitical backwater — except for its vast reserves of a certain vital commodity. Even then, that would have made it more a target for bigger powers to swoop in than an independent actor. But it just so happened that Saudi Arabia’s emergence as both a country and a major oil producer coincided quite closely with World War II and the beginning of the Cold War. As Zeihan puts it:

The Saudis lucked into a world in which their absolute security was a prerequisite for European security and East Asian security and American security.

Now those twin pillars that defined the first nine decades of Saudi Arabia’s existence — the oil market and American protection — are crumbling. Long-term growth in global oil demand is no longer a given, and Covid-19 is like a fever dream of all the worst aspects of that. Meanwhile, U.S. ambivalence toward the Middle East has been supercharged by the debacle in Iraq and the shale boom. Even if “energy dominance” has succumbed to its own inanity, U.S. dependence on Middle Eastern oil has diminished, not least in terms of feeling the need to keep it flowing to nominal allies. While America’s continued enmity with Iran is welcome, the shrug given to September’s attack on the Abqaiq oil-processing facility was a reminder the world has changed nonetheless.

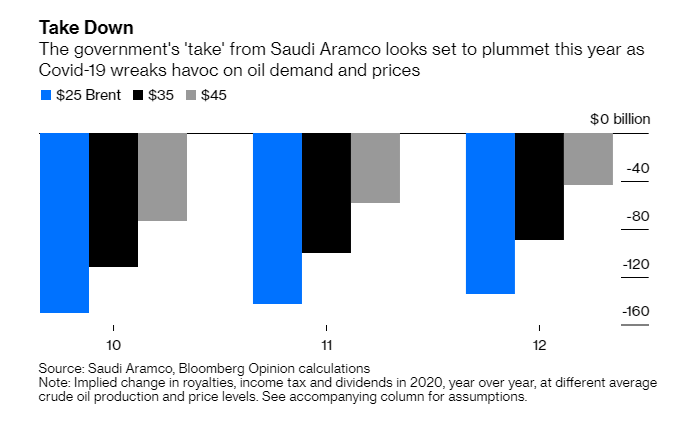

Saudi Arabia is trying to adapt. Doing so would have been easier with oil at $100 rather than $30. Oil provides about two-thirds of the government’s revenue, and it has been running deficits for six years already. According to Saudi Arabian Oil Co.’s accounts, royalties, income tax and dividends to the state added up to about $208 billion last year. This year’s take may drop by more than $100 billion, even with jacked-up oil production. 1

Against this stands the Saudi stash: almost $700 billion of net foreign assets. 2 This buys time, but not immunity. Financial markets notice sovereigns (and companies) cannibalizing their balance sheets long before the money runs out.

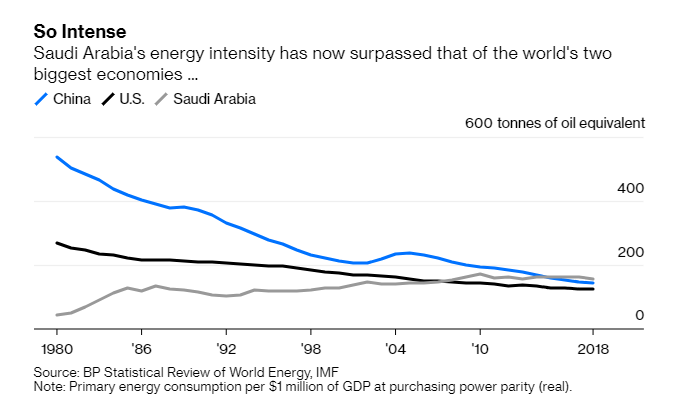

It’s hard to overstate the economic overhaul required. Two-thirds of the national workforce (as opposed to ex-pats) is employed by the government, with wages accounting for about 40% of public spending (which makes budget cuts tough to propose and even tougher to execute). 3 As it often does, oil has brought enormous wealth, but at the price of economic dynamism. One of the most striking aspects of this is how fuel subsidies have distorted Saudi Arabia’s own energy consumption. This does not look like a healthy, modern economy entering a more carbon-constrained world. 4

A recent study of the fiscal models of Gulf Cooperation Council members published by the International Monetary Fund concluded that getting onto a more sustainable path would require an immediate adjustment equivalent to almost a third of the non-oil-and-gas economy on average 5 . In other words, these countries are writing checks their future generations can’t cash.

At the same time, American backing is diminishing. It isn’t that the U.S. has withdrawn altogether; more that, as threatening letters from senators have demonstrated once again, it can’t be depended upon. In that light, the attempt to rope the U.S. into a brave new market-management scheme — call it OPEC-doubleplusungood — can be seen as an effort to preserve a much broader, but disintegrating, constellation of forces.

Far from prompting greater caution, Zeihan expects Saudi Arabia to respond to all this with aggression. Sporting a relatively weak military and surrounded by the proxies of arch-rival Iran, Saudi Arabia’s strategy will be to exploit its primary adversary’s over-extension, using its wealth to fund opposing proxies of its own. The idea being to light enough fires elsewhere in the region in order to avoid a direct, and likely devastating, war. Zeihan calls this “the geopolitics of arson.”

Like I said, it’s not a happy book. But while that remains a scenario for now, it isn’t pure conjecture. Saudi Arabia has long experience meddling in other conflicts from Afghanistan to Syria. And it has already adopted a more aggressive foreign policy in Yemen and with regards to Qatar under the de facto leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The emergence of MBS, as he is called, represents a jump from the ruling family’s old generation to its millennial incarnation. The ensuing centralization of power in his hands makes that far more than just a symbolic break. One of the most interesting aspects of this to emerge is his apparent embrace of populism, with his, ahem, anti-corruption round-up of fellow princes and easing of some restrictions on women being early examples of this.

In a fascinating recent article, Kristin Diwan of the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington puts these moves in the context of a broader shift toward a more overt nationalism as a means of legitimizing the state. This came to the fore in the recent IPO of Aramco, which ended up being more of an exercise in national pride than mere fundraising. Having encouraged citizens to borrow to buy the shares, the government has, Diwan writes:

… effectively multiplied the public’s exposure to oil risk, amplifying the cost of the current downturn. Still, it may not be the last sacrifice the Saudi state demands of its citizens. If the economic situation further declines, the Saudi government is likely to lean further on the new nationalist narrative promoting a strong work ethic and greater self-reliance.

It’s fair to say a headstrong ruler lacking institutional checks and fostering nationalist fervor to offset economic hardship is not a model that tends toward mellow outcomes. It does, on the other hand, dovetail all too neatly with Zeihan’s vision of global fracture. Oil bulls banking on Saudi Arabia to save the day this week should ponder what that means for the health of their market when this current crisis has passed.

- This is based on a simple valuation tool I put together for Saudi Aramco's IPO. Main assumptions for 2020 include net margins for downstream and chemicals operations of $1 per barrel and $100 per tonne and 95% and 90% utilization, respectively. Includes $2.1 billion of free cash flow from Saudi Basic Industries Corp., based on the consensus forecast and assuming 70% ownership for two-thirds of the year. Assumes natural gas production of 10 billion cubic feet per day and output of other liquids and ethane of 2.3 million barrels a day. Upstream costs per barrel of oil equivalent, including depreciation, at $6.

- Net foreign assets were $679 billion as of 3Q 2019 (source: Bloomberg Intelligence).

- "Public Wage Bills in the Middle East and Central Asia", International Monetary Fund, 2018.

- For more on this, see Jim Krane's book "Energy Kingdoms" (Columbia University Press, 2019).

- "The Future of Oil and Fiscal Sustainability in the GCC Region", International Monetary Fund, January 2020. Thisanalysis uses the Permanent Income Hypothesis. This estimates each country's total wealth and then modelslimiting expenditure to the estimated annuity value of that wealth while saving a significant portion of oil receipts in revenue-generating assets whose dividend income is meant to replace oil revenue in the future. The authors found that, on average, the GCC countries would require an immediate fiscal adjustment equivalent to 32% of their non-hydrocarbon economy in order for future generations to equally share the existing level of wealth.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Liam Denning at ldenning1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

8 April 2020