'The human fingerprint is everywhere': Met Office's alarming warning on climate.

Exclusively compiled data from the Hadley Centre’s supercomputer shows alarming climate trajectory.

The human fingerprint on the climate is now unmistakable and will become increasingly evident over the coming decades, the UK Met Office has confirmed after 30 years of pioneering study.

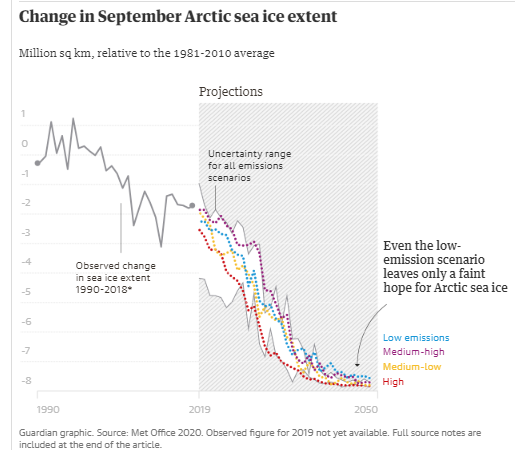

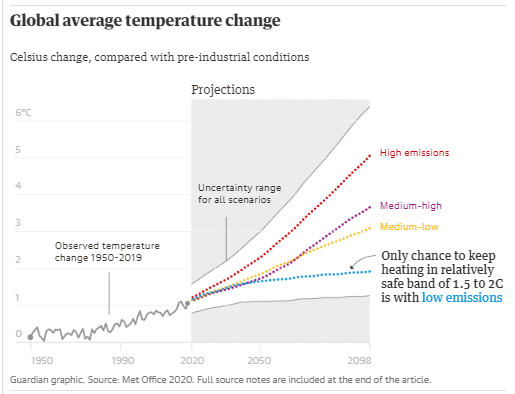

Since the 1990s, global temperatures have warmed by half a degree, Arctic sea ice has shrunk by almost 2 million km2, sea-levels have risen by about 10cm and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased by 60 parts per million (17%), according to figures exclusively compiled for the Guardian to mark the 30th anniversary of the Met Office’s Hadley Centre for climate science and services.

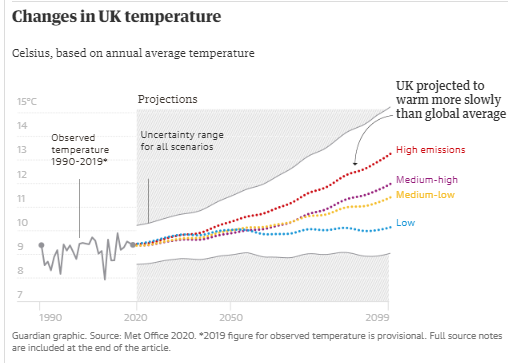

The data highlights how a young generation has grown up in a climate unprecedented in a millennium. Future projections suggest that by mid-century a 60-year-old Briton is likely to be living in a climate 1.2C warmer than when they were born.

Scientists at the Hadley Centre, which has been on the global frontline of climate monitoring, research and modelling since it opened in 1990, said early theories about fossil-fuel disruption have been proven by subsequent facts.

“The climate now is completely different from what we had 30 years ago. It is completely outside the bounds of possibility in natural variation,” said Peter Stott, a professor and expert on climate attribution science at the centre.

In the Hadley Centre’s early projections, he said, scientists forecast 0.5C of warming in the UK between 1990 and 2020 as a result of emissions from oil, gas and coal: “We got it spot on.”

With new heat records being broken with increasing frequency, he said global temperatures were now above any level in the Met Office measurements since 1850, or indirectly calculated through tree rings going back thousands of years. Carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere are also higher than anything seen in million-year-old ice cores. “We are seeing an unprecedented climate,” Stott said. “The human fingerprint is everywhere.”

The impact was less obvious in 1990, when the centre opened in conjunction with the publication of the first report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - both were overseen by the UK scientist John Houghton, who died earlier this year.

At the inauguration, the then prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, said the UK needed a world-leading climate centre to assess the “serious consequences” of greenhouse gas emissions. “What it predicts will affect our daily lives. Governments and international organisations in every part of the world are going to have to sit up and take notice and respond,” she said.

Thatcher, who studied science at Oxford, needed little convincing, but she had to overcome a sceptical cabinet. Atmospheric physicists had been warning oil companies and policymakers about the dangers of fossil fuels for decades, but the “greenhouse effect” was still a relatively novel concern for the broader public. Nobody felt a change. The world had already warmed by about half a degree from pre-industrial levels, but this was low enough to be within natural variation.

Few people knew the difference between short-term “weather” and the “climate”, which is usually measured over a much longer period of 30 years.

Back then, there was also considerable scepticism about the ability of meteorologists to forecast change, even on a daily basis. Memories were fresh of the BBC weatherman Michael Fish infamously reassuring viewers that fears of a hurricane were unfounded, just hours before the fiercest storm in generations hit the UK.

“It was unglamorous” recalls James Murphy, a science fellow who was posted to the Hadley Centre from the beginning. “But the mood in the first decade was one of great excitement, because it was a chance to do a lot of pioneering research in a growing field.”

As acceptance and importance grew, so did scepticism. Critics, often funded by oil firms, pushed back against climate science because they did not like its political and economic implications. Ahead of the climate summits in Kyoto (1997) and Copenhagen (2009), fossil fuel companies funded misinformation campaigns to cast doubt on climate models.

The Hadley Centre remained focused on science. Researchers expanded and refined their models by incorporating new knowledge on biological carbon cycles and the likely impact of fossil fuels not only on temperature, but on Arctic ice, sea-level rise, flooding, storms, droughts and other atmospheric phenomena.

Supercomputer advances enabled much greater precision. Early models mapped the impact on grid cells of 300km on each side. Today that is down to 2.2km, which allows detailed predictions of which stretches of river basins and coastlines will need the most protection.

Researchers are discovering the impacts go far beyond the initial focus on average temperature. Heat records are being set with increasing frequency. Rainfall patterns are noticeably shifting beyond natural variation. Arctic ice is shrinking faster than expected. The rising seas have already left some places, such as Fairbourne in Wales, below spring-tide levels.

By 2050 – the year the UK plans to achieve carbon neutrality – the direct impact on Britain will be moderated by the surrounding ocean and there may be opportunities to plant new crops, but these benefits will be dwarfed by trade disruption, migration, humanitarian disasters and shifting ecosystems.

“Overall it’s bad. The negatives outweigh the positives,” said Richard Betts, a Met Office scientist who is leading scientific analysis for the next UK climate change risk assessment. “It stands to reason that if the world keeps gets hotter and hotter, sooner or later we’ll reach the point where it is first uncomfortable and then hard to function. This won’t be seen in the UK, but in parts of the world that are already hot and humid it could increasingly get too hot to function.”

The Hadley supercomputer calculates myriad possible pathways depending on how much carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gases enter the atmosphere. The good news is that the worst-emissions scenario, known as RCP 8.5, is considered less likely than before because the global coal industry has not grown as feared. The bad news is current emissions trends (which lie between the RCP 4.5 and RCP 6 pathways) could take the planet to 2C warmer than pre-industrial levels by mid-century, which will increase storm damage, heatwaves, sea-level rise and the already great risk that the Arctic will be ice-free in summer.

The climate trends are based on multiple-year averages rather than year-on-year comparisons, which are more subject to natural variation.

Even the current best-case scenario – RCP 2.6, which is roughly in line with the Paris agreement – would leave the world hotter than today.

“What stands out is that even in the lowest current scenario, we get warming. We’ll need to prepare and adapt,” says Jason Lowe, the head of climate services at Hadley. He predicts extreme summer heatwaves, such as those seen in 2018, will become the norm rather than an exception.

“As a scientist, I want to narrow the uncertainty so the information is as good as possible so we can plan. I think of the generations to come. I have a nine-year-old daughter. I find myself wondering which of these pathways we will be on when she is 80 or 90.”

More extreme results are possible at both ends of the spectrum. The next set of climate assessments will introduce a more ambitious best-case scenario (RCP 1.9) that would mean a faster transition to zero-carbon energy and a greater chance of holding temperature rises below 1.5C. But the situation could worsen rapidly if the climate hits tipping points, such as the collapse of the west Antarctic ice sheet.

“There are still dangers out there that we don’t fully understand,” said Stott. “Much of the uncertainty lies on the bad side. It could be terrifying. Can we grow enough crops to feed the population? Can we cope if some places are battered by storm after storm?”

Such concerns explain why the anniversary cannot be entirely triumphant. Despite growing evidence of climate risks, governments have been slow to act. Apart from downward blips such as the 2008 financial crisis and the coronavirus lockdown, emissions have steadily increased. The Hadley Centre’s work now is not only about predicting impacts, but preparing for them.

“Reality has proven that what we were saying 20 to 30 years ago was right. As scientists, that is vindication. But on a personal level, I hoped we would track a different emissions trajectory from where we are now,” Stott said.

“The worry is that we are now taking risks globally that we don’t fully understand ... there will be no winners of climate change if we continue. Scientific evidence has been around for a while. It is time it was taken seriously.”

Data source notes

Observed September Arctic sea ice extent from HadISST.2.2.0.0 (selected as single source from Met Office climate dashboard.) Emission scenarios are the mean averages for climate scenarios SSP1-2.6 (low), SSP2-4.5 (medium-low) and SSP5-8.5 (high).

Observed changes in global mean sea level (GMSL) in metres from Nasa satellite data relative to 1981-2000 average. Emissions scenarios are 50th percentile projections from UKCP18 estimates, RCP2.6 (low), RCP4.5 (medium-low), and RCP8.5 (high).

Observed annual global temperature data from HadCRUT4. Emissions scenarios as above.

Annual temperature for the UK based on HadUK-Grid observations. Emissions scenarios as above.

All hindcast data omitted.

27 May 2020

The Guardian