A hippopotamus: why did I have to be a hippo? Why not a hawk, a hare, a magnificent horse?

I grabbed my friend’s arm, frozen, and imagined my tombstone

When you are a child, the first letter of your name will associate you with one animal or another. Mine was, inevitably and to my great disappointment, a hippo: an animal of thick, grey skin, whiskers sprouting from its cheeks, feet that were far too small for its body. Hippos weren’t even cute, I knew this: their strange mouths, cheeks at the end of a long nose, hid (where? how?) vast discoloured teeth which they used to chomp anything from antelope to zebra. I wanted my name to start with an elegant lowercase h: a letter that also happened to be the shape of a miniature giraffe. Instead I was H for Hippo, stocky and sturdy, like a Kalabari mask from Nigeria.

Hippos eat grass instead of fish, according to Kikuyu legend, because of a deal with God: the hippo wanted to swim in waters cooled by the snow from Mount Kenya but God worried he would eat his little fishes, which were very dear to him. (And why wouldn’t they be? Little silver fish, quick and made of light.) So the hippo promised that, at night, he would emerge from the water “every time that food passes through my body, and I will scatter my dung on the earth with my tail”.

Again: why did I have to be the hippo? Why not a hawk, a hare, a magnificent horse?

As it happened, we went on holiday to a lodge on the South African side of the Limpopo River whose lawns were mowed by hippos: they emerged at night, large black shapes with small, knuckley hooves. One night before dinner, a friend and I – her name begins with S, for swan, snake, seahorse – went swimming in the pool, which was strictly against lodge policy. We were so focused on breaking the rules we didn’t think about why they were in place until we climbed out and started down the pathway that led to our chalet.

We heard the sound: the tug and tear of grass being pulled from the ground by megaherbivore lips. A metre away: a huge pendulum head moved a centimetre sideways, then its feet stepped to join it. I grabbed my friend’s arm, froze, and imagined my tombstone: Here lies H: “for hippo”. Ha Ha Ha. But my friend – S, for saviour – pulled my arm gently and we kept walking, holding small, knuckley hands, staring straight ahead, then let go and ran all the way home. The hippo spared us, perhaps because it knows what all hippos know: sometimes a faceless omnipotence tells you where you can and cannot swim, and you just have to find a way.

A decade later the same friend and I were on a kayak in Zimbabwe, at Mana Pools, a national park where elephants rock their enormous bodies on to their back feet so they can reach the leaves at the tips of trees. In the water we saw two ears, tortellini ready to be scooped up and eaten. Then they disappeared again: the world’s hungriest submarine. As we paddled on we were followed by a line of bubbles – who knew bubbles could be so frightening?

Hippos can’t swim – they sink to the bottom the moment they enter the water, and propel themselves forth, trampling, in the Okavango, desire lines through the weeds that open the swamps up to every other creature – but some can surf. In Gabon, hippos catch saltwater waves from one beach to the other.

The expression on the face of Man Turning Into a Hippo, a sculpture by Bernard Matemera, seems to show a person aware that they are changing, probably into something objectionable, but maintaining hope that there will be something good about what is to come: someone to see only the best in a hippo.

Have an animal, insect or other subject you feel is worthy of appearing in a very serious column? Let me know: helen.sullivan@theguardian.com.

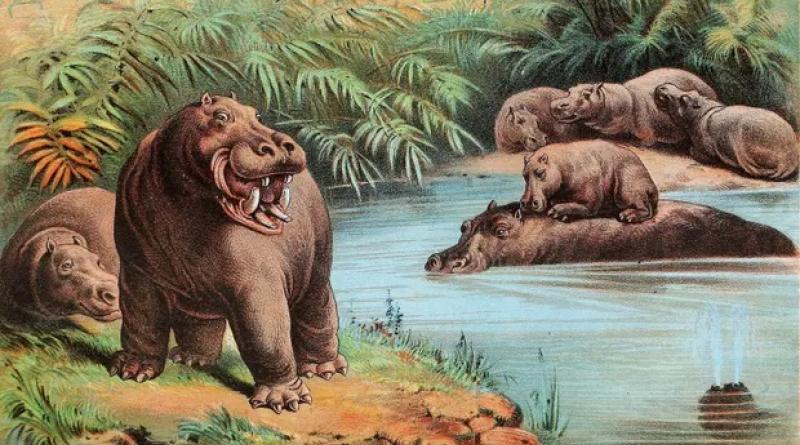

COVER PHOTO: Hippos eat grass instead of fish, according to Kikuyu legend, because they made a deal with God. Illustration: Iconographic Archive/Alamy